Yoko Ono Half-A-Room, Lisson Gallery, London, 1967 Photo: Anthony Cox © Courtesy LENONO PHOTO ARCHIVE

Yoko Ono’s We Are All Water, 2006, lines up identical glass bottles of water, each labeled with the names of well-known figures such as Groucho Marx, Andy Warhol, Dwight Eisenhower, Joseph Beuys, John Coltrane, and John Lennon. “We’re all water in different containers,” writes Ono in 1967. “But even after the water’s gone we’ll probably point to the containers and say, ‘that’s me there, that one.’” Ono concludes, “We’re container minders.”

Guilty as charged. I am a furtive container-minder. But wandering through YOKO ONO: HALF-A-WIND SHOW at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, the most comprehensive survey of Ono’s career to date, I soon give up trying to pin Ono’s work to a given practice or idea. The retrospective’s title, which comes from Ono’s small 1967 show at Lisson Gallery, emphasizes the artist’s habit of recycling events, instructions, and performances. “Retrospection is Prospect’s half,” writes Emily Dickinson, and the Schirn retrospective successfully looks back while also honoring the open and fluid nature of Ono’s work and her ongoing practice.

To enter the Schirn Kunsthalle, visitors must cross a three-story rotunda, where Ono’s large scale Morning Beams (1997, 2013) and Riverbed (1996, 2013) have been installed. Above a meandering line of large rocks, nylon ropes are suspended from the ceiling and fall in imitation of light rays. The exhibition proper is spread across two second-floor rooms, and a chronology of the artist’s life unfolds just outside the exhibition on a balcony encircling the rotunda.

From the second-floor balcony, one might look down onto the rotunda’s “riverbed,” or across to the first-floor balcony (outside the Art Education workshops), where I noticed a trolley stacked with plinths. What I didn’t notice is that Ono had written on the walls of the first-floor balcony in a repeat performance of Blue Room Event, originally conceived in 1966. Later, I discover tiny handwritten sentences: “stay until the room is blue”; “this room moves at the same speed as the clouds”; and “this room slowly evaporates every day”. Blue Room Event, occurring as it does in a part of the Schirn that isn’t an official exhibition space, is left for visitors to stumble upon. As always, Ono raises questions about what counts as an “event”: her writing the words, me discovering the words, or the moment I imagine the space in which I stand as blue and slowly evaporating.

Yoko Ono Half-A-Wind Show. A Retrospective Exhibition view © Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt 2013 Photography: Norbert Miguletz

Informality and intimacy characterize the exhibition. Fragile objects are enclosed in glass, but visitors are often invited to touch; the phrase “Get Involved,” stenciled on the floor around many objects, cues visitors they can interact with the works. Listening stations allow visitors to take their time perusing Ono’s musical output from late-1960s experimental recordings and sessions with Lennon to recordings of the Yoko Ono /Ono Plastic Band and recent collaborations with Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore.

Ceiling Painting, Yes Painting, 1966 Text on paper, glass, metal frame, metal chain, magnifying glass, painted ladder Ladder: 183 x 49 x 21 cm, framed text: 64.8 x 56.4 cm Collection of the artist © Yoko Ono

Ceiling Painting, 1966, the work over which Ono and Lennon first met, is the only moment in the retrospective that feels like staged nostalgia. In the original installation at London’s Indica Gallery, one climbs a ladder and looks through a magnifying glass at the word “YES” painted on the ceiling. In the Schirn, the work is displayed on a raised platform. Visitors can’t climb the ladder, and the word “YES” is painted on a square of Plexiglas suspended from the museum’s ceiling. This is not really a “ceiling painting” but the representation of Ceiling Painting – thereby turning Ono’s original installation into a tableau, a piece of theater that represents an iconic moment.

What the retrospective makes clear is just how prolific and radical Ono was from a very early age. Lighting Piece, a performance and film that consists of lighting a match and watching until its flame goes out, is executed as early as 1955 when Ono was 22. Her marriage in 1956 to avant-garde composer Toshi Ichiyanagi brought her into contact with John Cage and his circle. In 1959, she begins performing her own poetry at events sponsored by the Japan Society. In 1960, she and La Monte Young organize performances and exhibitions in her loft. Guests include Marcel Duchamp and George Maciunas who, in 1961, coined the term “Fluxus.” Ono is often overlooked as a significant, early participant in the activities of an international group of artists whose irreverent, Dada-like experiments sought to erode the distinction between art and life.

Particularly interesting is the Schirn’s presentation of the development of Ono’s work from paintings to instructions. A generous display of large documentary photographs show the artist’s painting exhibition in 1961 at Maciunas’s AG Gallery. Pieces of cloth dyed with Japanese ink, the paintings include instructions for viewers to “complete” them by, for example, adding water or walking on them. A year later, Ono’s solo exhibition of “paintings” in Tokyo featured instructions only; these original instructions, written in Japanese, are also on view.

As instructions, Ono’s “paintings” avoid being confined to any one visual or written object.

Like the instructions of her Fluxus contemporaries George Brecht and La Monte Young, Ono’s instructions have their origins in the musical notations of experimental composers like John Cage. The instructions are really event scores (a point developed by Liz Kotz in her book Words to Be Looked At; Language in 1960s Art).

But Ono’s instructions, later collected in Grapefruit. A Book of Instructions and Drawings, 1964, are different in tone and content than those of other Fluxus artists such as Young and Brecht who use matter-of-fact language to score simple actions that could be executed multiple ways. In 1960, Young instructs “Draw a straight line and follow it.” A Brecht score reads “Exit.” In contrast, Ono’s instructions are impractical or impossible and must be imagined, such as the 1962 instruction to “watch the sun until it becomes square.”

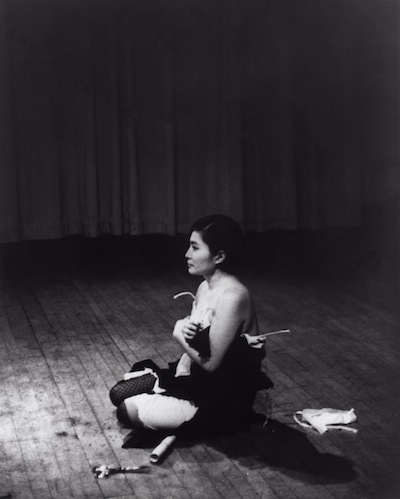

Yoko Ono Cut Piece, 1965 Performed by Yoko Ono Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, 1965 Photo: Minoru Niizuma © Courtesy LENONO PHOTO ARCHIVE

What the retrospective also makes clear is that Ono’s performances and films anticipate the feminist practices and body art of the 1970s. Having only seen photographs of Ono’s performance Cut Piece, 1964, it’s wonderful to have an opportunity to see a documentary of this performance in which Ono kneels on stage while audience members are invited to come on stage and cut a piece of her clothing (to be kept as a “souvenir” of the performance). While photographs present the artist as vulnerable and acquiescent in the hands of the audience, the film is also unsettling because the act of watching seems to implicate one in the ritual disrobing of the artist.

Yoko Ono Filmstill from Fly, 1970 16 mm film transferred to digital Color, sound, 25 min Collection of the artist © Yoko Ono

I also found Ono’s film Fly, 1971, more disturbing – and provocative – than I’d assumed based on descriptions. The camera follows the movements of a fly as it crawls among the curves and folds of a naked female body. Because of the association of flies with rubbish and death, it is difficult for me not to read this as a feminist indictment of the treatment of women. Then again, Ono resists the body as a symbol; a track on the 1971 album “The Fly” asserts “Body is the Scar of Your Mind” and the work We Are All Water, 2006, claims bodies are just containers.

Riddling the mind-body problem is a familiar game for Ono, as in my favorite work, the 1964 Morning Piece in which glass shards are labeled with dates. Each shard represents a morning in the future, on sale as part of 1964 and 1965 performances in which the artist peddled “future beginnings.” The 17 remaining mornings (“February 3, 1987 after sunrise” or “March 3, 1991 until sunrise”) are now in the past and can no longer be sold as future mornings. Or can they?

Morning Piece, a celebration of beginnings, draws attention to Ono’s practice of challenging habits of consumption. (Air Dispensers, 1971, sells capsules of air and Sky Machine, 1961/1966, dispenses cards penciled with the word “sky”.) Morning Piece also brings up the experience of time in Fluxus works. The point of most Fluxus instruction is that a given event can be done at any time by anyone anywhere so the “work” remains open and not pinned to time and place.

In keeping with the spirit of Ono’s work, the Schirn’s Half-A-Wind Show successfully negotiates the line between historical context and the present moment of open, recurring work, underscoring the artist’s own point about the impossibility of “keeping” time.

YOKO ONO: HALF-A-WIND SHOW, on view through May 12, will travel to the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, the Kunsthalle Krems, and the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao.

Comments on this entry are closed.