As an installation, the components of Swedish-born artist Carol Bove’s exhibition at MoMA, The Equinox, practically vibrate together; as a set of sculptures, not so much. Currently, Bove’s more monumental sculptures are on view on the High Line; in contrast, her MoMA show features seven sculptures of varied scale, all arranged seemingly randomly on an elevated, white platform.

My expectations were not very high, given that, as the press release cites, the show deals with themes of utopia and the relationships between man and nature, the structured and the organic, and the new and the discarded. I feared tired ideas of man’s destruction through consumerism and the superior quality of the natural. I was pleasantly wrong. The Equinox is not a moral directive, but rather an examination of beauty in equality, achieved through the works’ repeated elements, juxtapositions, and placement. If it weren’t for the blandness of the individual sculptures, I would have loved the show.

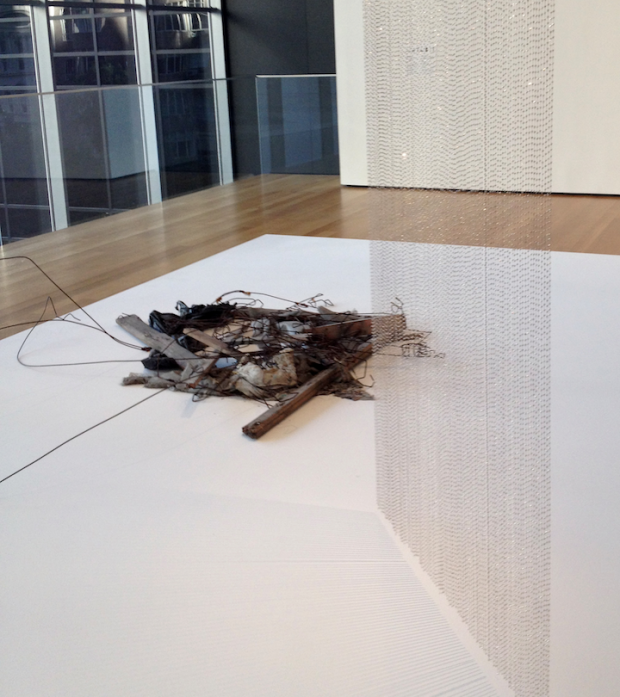

It’s no surprise that a show named The Equinox works wonders with balance: “Taoism” is the word that comes to mind for the arrangement of the sculptures. For example, a glitzy curtain— when seen from standing at a certain angle—hangs before a pile of, well, junk. This positioning does not give the impression that the curtain is eclipsing the old, or that the pile of discarded matter has more value than the attractive new-looking-ness of the curtain. By displaying the two, opposites in their own right, in conjunction, a balance is reached that is more than the sum of their individual worth.

This balancing act of opposites is made more explicit when the sculptures interact directly with one another through repeated motifs. A golden cube can either hang precariously in a system of found, organic objects (left, “Triguna”) or stack itself in a stable network of geometry (right, “Terma”). Both of these sculptures have a beauty to them—indeed, they’re the two strongest pieces in the show. “Triguna” finds beauty in nature, its elements so delicate that they move with the wind of passersby; “Terma” finds beauty in man’s creation, through the satisfying solidity and cohesiveness of basic geometry. Together, they offer both their individual merit and the satisfying tension of their interaction with one another.

The other two repeated elements—rusted iron and found wood—have a rather different effect. Two structures with found wood and rust lie across from one another on opposite sides of the display, and a third piece roughly equidistant from the two, also contains rust. Though these sculptures—a piece of driftwood against an iron pole, a collection of scrap pieces, and an iron joint—are obviously not identical, they do not rely on the same balancing of opposites as the gold cube. Rather, their dispersion creates their relationship, producing a sense of unity across the platform.

Indeed, when taken together, all these sculptures create something quite like magic. The Equinox itself feels precarious, resting on a series of effects that so nearly don’t work. Where, as it stands, each piece complements its opposite, the differences could easily be seen as clashing or disjointed, and their relationships could feel stale. This fragility, too, contributes to the mystical balance of The Equinox. The prominent use of disconnect in the individual pieces—the sectioned plastic tube and the large, iron connector piece connected to nothing—emphasizes the paradoxical unity. Indeed, the whole installation rests on a series of contradictions that twist our logic to the point of otherworldliness.

Unfortunately, The Equinox is not just an installation. The press release doesn’t use that word, instead dubbing it “an arrangement of seven sculptures.” As individual sculptures, the pieces fall flat. With the exceptions of “Triguna” and “Terma”, each work bears little interest on its own. The large, plastic tube, which, as part of the exhibition, shows disconnect and recalls balance through its resemblance to a yin-yang, becomes just a squiggle. The iron joint connected to nothing is not a paradoxical unifier but a piece of metal not doing its job. The pile of junk is a pile of junk; the piece of driftwood against iron is a piece of driftwood against iron; the glitzy curtain is a chintzy reminder of seventies interior design.

But I cannot change the intention of the work and, as it stands, The Equinox, is an unremarkable collection of sculptures, made into a fantastic (in the literal sense) experience by their unity.

Comments on this entry are closed.