This interview series is produced in partnership with MATTE Magazine, a publication produced by writer and curator Matthew Leifheit that focuses on the work of a single photographer per issue.

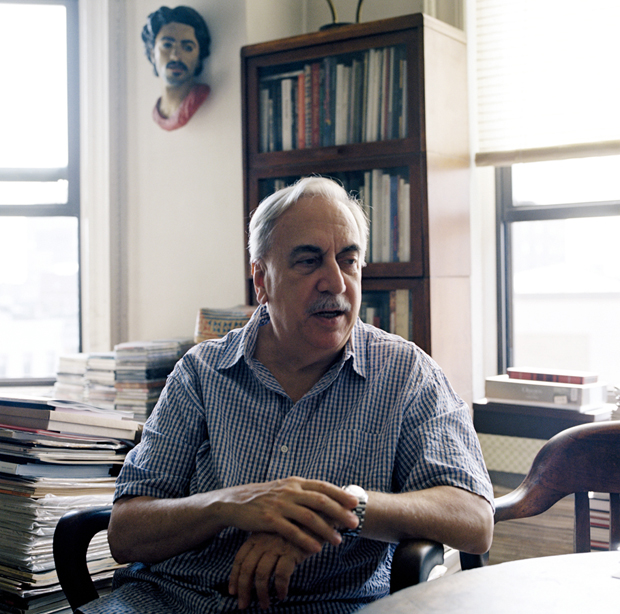

Vince Aletti has been allotted more firsts (and almost firsts) in his life than the average person. He was the first person to write about disco. He’s one of the few critics to build a career on photography criticism, and regularly reviews photo shows for The New Yorker in addition to writing a regular feature on photo books in Photograph Magazine. He is the only person to have penned, “This is Not a Fashion Photo” a regular online column in W Magazine, where he choses pictures that look like they were made for a fashion publication but weren’t. It’s all part of his interest in niche culture, photography and fashion. I sat down with Aletti to talk about how he’s spent the last forty years studying, curating and reporting on culture.

I’m interested in your path as a writer. You started writing about music?

When I came to New York in 1968, one of the guys I went to college with remembered I used to write, and he was involved with a newspaper called The Rat. The Rat was a radical underground newspaper published in this neighborhood [East Village] with very serious leftist politics. But they also covered music and culture. I started writing for The Rat, but it wasn’t like I was getting paid or anything.

At what point did you start writing for other people?

Fairly quickly. I wrote early on for Rolling Stone, Fusion, Crawdaddy, and a number of other smaller NY papers about music. Around 1970, I got very serious about freelancing, mostly for Rolling Stone on R&B, and black pop music. It was the music that most interested me, and it ended up being a valuable niche for me, because there were not a lot of writers who were focusing on that. So when an Aretha album came up, or the Jackson 5, or Parliament, I was often the first person they thought to ask.

And that led into disco, another niche.

Disco is just an evolution out of R&B, black pop, Motown, Philly International. All the music I liked was part of the early development of disco. So it was something I inevitably fell into. Just the same way I was one of the few critics to write about black pop, I was really the only critic to take disco seriously. I was going out dancing. Had I not been going to clubs, I wouldn’t have heard disco evolve, and I also wouldn’t have been involved in it that way a dancer is involved in that music. Most critics were not dancers or clubgoers, so they really didn’t understand disco from the point of view of the way the music was designed.

When did you start meeting photographers and writing about photographs?

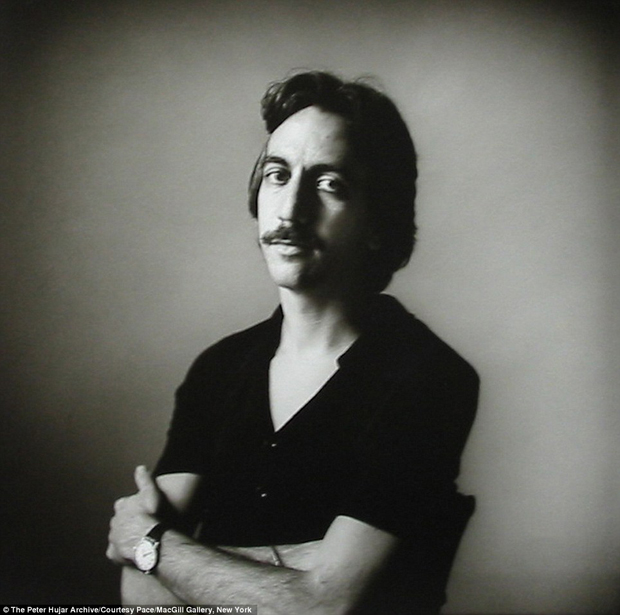

I had been going to galleries since I came to New York, and I was interested in photography because I knew photographers. Peter Hujar was a good friend of mine. So I’ve always been interested in photography from the point of view of the working photographer. I’m curious about why people do what they do and how they make a living out of it, as well as the art involved. And knowing someone who was struggling to make a living made it very real to me. At that point (early to mid ‘80s), I was working at the Village Voice. I was a regular writer at first, with a regular column on singles, and a column on music videos.

But I was dissatisfied with the reviews and the attention to photography at the Voice, and when there was a chance to start doing it on my own, I did. I started writing very brief weekly reviews of photography shows for the calendar listings. And that made a very easy transition. I was writing a hundred words. And that’s essentially what I’m still doing.

I started writing a series of full-page profiles of photographers whose whose work interested me. People who were having their first or second show. The first one I did was Dawoud Bey. Barbara Ess. Neil Winokur. Sally Mann. I also did profiles of people who were involved in the world of photography: I wrote about Maria Morris Hambourg when she was the photo curator at the Met, and Peter Galassi, when he took over John Szarkowski’s job at the Museum of Modern Art. People whose work made me wonder why they did it and where it came from in their lives.

On the subject of Peter Hujar—I interviewed the executor of his estate, Stephen Koch, last week, and he gave me a catalog for a show at the Gray Gallery where you were interviewed. So you were friends with him, and he’s part of the reason you became interested in photography, from knowing him personally?

Right. I met him through a good friend of mine who was his boyfriend at the time. This is 1968 or 69. After they broke up, I remained friendly with Peter. When I moved here, Peter lived directly across the street from me, directly above the movie house [points out the window]. So we were neighbors but we were also close friends. He was really a great person to talk to about pictures. Not a theoretical person, but somebody who really looked at pictures. He would come over, and we would sit and pour through fashion magazines because both of us were interested in fashion photography.

I don’t remember that we went to galleries much together; I tend to do that on my own. But we talked a lot about work. I looked at his work, and it was really interesting to me to see how someone creates a career in photography, to see the difficulties of that. The strain of trying to get your work out into the world while you’re making it, while you’re engaged in it. But primarily Peter was a great pair of eyes to share photography with. And I don’t think I would have gotten so caught up in the world of photography had it not been for him.

You were also kind of a patron, right? You hired him to take some pictures.

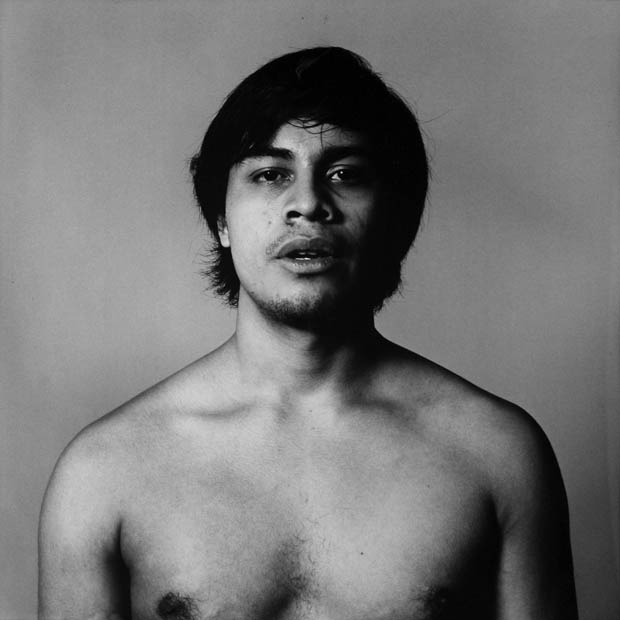

When I had enough money that I could say, “Peter, would you photograph this boyfriend of mine?” I knew that he would make a picture that really meant something to me. And knowing that he was always struggling and needing commissions, when I could afford that, it was a pleasure.

They’re personal pictures, for you. But it was also an experience of understanding how he saw.

It gave me some insight into the person from his point of view. He photographed this friend of mine named Manny. It turned into something much more interesting for Peter than I had expected it would be. He used four pictures from that session in books and shows later. And that’s not typical of Peter. There were times he didn’t even get one picture he was happy with. So I was really intrigued that he and Manny had connected in this way. I always tried to set up people whose looks I liked with Peter, and now I miss him as a photographer, if only for that reason, because I always want to have a real portrait of people that I like.

So you’re writing about photography for the Voice. At what point does it start to consume you? Because it seems like you were consumed.

I’m consumed in many different directions. I became increasingly focused on photography and started moving away from music in the mid-80s. I was still reviewing Madonna and Aretha. I didn’t feel like the authority that I once was. I couldn’t keep up with it. I never stopped being interested in music, but I didn’t feel as engaged as I was before, and I realized that I couldn’t do both. So I really did switch entirely to photography in the late ‘80s.

Shortly after that I became the art editor at the Village Voice. That put me in a different position, and made it necessary for me to focus very completely on art and photography. At the beginning I was editing Peter Schjeldahl and Kim Levin. Both of those writers also taught me a tremendous amount about writing, and about ways to approach art.

Especially Kim, because Kim was writing the brief “choices” about art. So both of us were learning how to compress something into 100 words. And she is a master at that. I learned a lot from reading and editing her and Peter, although he really required no editing. And then when Peter left for The New Yorker, I brought in Jerry Saltz.

Photography in the late ‘80s is probably a very different world than it is now. That’s about when it was starting to be understood as Art, right?

There had already been plenty of museum exhibitions, but it was when photography started being understood in a larger context. When I first started writing about photography, you really only saw it in a number of small photo galleries that didn’t get much attention at all. It wasn’t like there were people like Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, or Jeff Wall who were making huge pictures that got attention outside the photography world. So yeah, a lot changed. The Pictures Generation had a lot to do with that, but also there was a growing interest in the history of photography. Galleries like Matthew Marks, who was primarily showing contemporary art, would show Robert Adams, and already had Nan Goldin in the stable. So there was a real opening up of photography, and a real sense that it was not some isolated ghetto world. It gave me a much broader range of things to write about, and many more serious shows to pay attention to.

In your opinion, what makes a great photograph?

My immediate reaction is, it has something soulful that I can relate to. For me, a great photograph is a portrait. That’s what I’m most drawn to. But then, a great photograph could be James Welling’s pictures of draped fabric and bits of dust.

I have to feel some kind of emotional connection. Something that touches me and makes me feel like the work is coming from a real place. There’s a lot of work being made that’s all about strategy and ideas. I’d just as soon read about that work as see it.

When did you become interested in pictures of men?

[Laughs] From the very beginning. I was never not interested in pictures of men.

It started with physique pictures, which were inexpensive, and to me, surprisingly rich. There was a store not far from me called Physique Memorabilia, that was a kind of loft space that you had to know they guy who ran it in order to get in. It was a place I could go on a rainy day and spend a couple of hours looking through bins of photos. It was like a dollar a picture. It was for me a way of training my eye in a really specific area. Identifying styles, finding a range of pictures that were interesting, and also the prints themselves were really beautiful. Very handsomely done in terms of the quality and the paper. So I was coming home with these really great little images, mostly of naked men. And that gave me the beginning of a collection, and a beginning of a way of thinking about pictures of masculinity, and the way men are portrayed.

It seems like you see a lot of value in specificity.

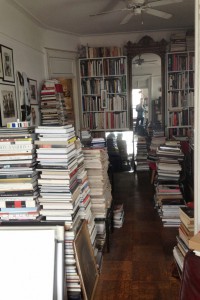

Niche, right. At the same time, partly because of Peter, but partly because of my interest in Avedon and Penn, I was spending more time with fashion magazines. As you can see, there’s all these pictures of men, but also piles and piles of magazines with pictures of women. So there is an odd kind of balance here.

I became more and more obsessed with collecting fashion magazines at the same time I got serious about collecting photography.

Collecting fashion magazines? How do you mean?

Like putting together a complete run of Harpers Bazaar and Vogue.

You’ve curated a series of shows for ICP on fashion.

I’d been interested in fashion for a long time, and it’s one of the things I wrote about at The Voice.

So, an issue of Vogue would come out, and you would review the photographs in it?

Sometimes. This is one of the many things that was fun about the Voice. Once you were there, it was possible to follow your instincts. Since I was not only writing the photo reviews, but editing the section that they appeared in, I could do whatever I wanted to. So, there were times when alongside reviewing a photography show, I would review the latest Steven Meisel campaign for Calvin Klein. For me, that was equivalent to a great photography show, and it was much more accessible to everybody. So yeah, there were times when I would review an entire issue of a magazine, but more often I would review a fashion campaign, especially if it appeared on billboards and was very visible to a lot of people. Because I thought, and I continue to think, that there are great fashion photographers at work, most of whom never have a show, rarely have a book, and aren’t seen outside of the context of a magazine.

The show at ICP I worked on with Carol Squiers, Weird Beauty, was all about fashion in the magazine. Party because both of us realized we were working with material that had never been in a museum before, that had rarely been even on a wall. And a lot of the photographers we were working with weren’t making prints for exhibition. So we were really happy to just put tear sheets on the wall.

So where do your interests lie now?

My interests haven’t varied from the kind of images I’ve been collecting and thinking about for a long time. Still fashion, still pictures of men. My interests as a critic aren’t narrow at all. I have to write about everything. I’m interested in photographic abstraction; I’m interested in conceptualism when it’s well done. I’m interested in photobooks. It’s something I’ve been interested in a long time, and I’m glad photobooks are getting more attention.

Before the 80s, when there were no photo galleries (and very little place for photographers), the book was their way to get the work out into the world. Books were key to the understanding of photography for a lot of people, and to its development as an art form. The book continues to be really important to photographers as a way of organizing their work; sometimes it’s more important than an exhibition.

Do you think that’s true today?

Absolutely. I think it’s a way for photographers to shape the work themselves—by way of sequencing, choosing a scale, thinking about reproduction— and the way it’s presented to the world. It lasts longer than a gallery show. So I think a lot of photographers—Alec Soth is one example— really think about books as their prime output.

You started to write for The New Yorker and Photograph when you left the Voice in 2005?

I was determined to be a freelancer for a while, but I got hired right away by The New Yorker to write weekly reviews of photo shows. So that’s my main platform at the moment. Every other month I have a column in Photograph about photobooks. I’m writing a little more regularly for Artforum. And I started a regular web feature for W magazine’s website called “This is Not a Fashion Photo” where I choose pictures that have kind of a fashion feel to them, but they weren’t made for fashion.

What is the goal of blurring the line between fashion and in some cases vernacular photography, and fine art photography?

For me it’s a way of getting people to think in a more open way about fashion. Most fashion photographers are not influenced so much by early fashion work—most of them could care less about Horst and Beaton and all the people who came before them. They’re really more influenced by Nan Goldin and Walker Evans and Francesca Woodman: people who didn’t make their pictures with a fashion intent. But when you look at Nan Goldin, you could really see those pictures as fashion pictures.

So, you’re doing many things right now.

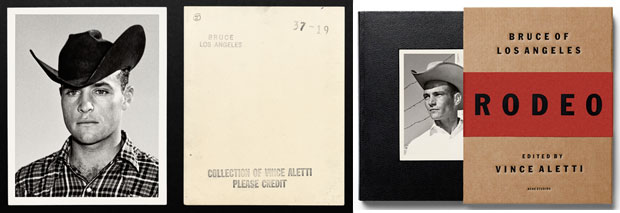

I did this book for Acne, the clothing company, and it was primarily distributed in their stores this spring. These are pictures primarily from my own collection. They’re Bruce of L.A., who is essentially a physique photographer, but who spent a lot of time at rodeos. I really think the guys are charming, the pictures are kind of great, and I like the authenticity of the setting, the people, everything. I thought it was a great body of work that hadn’t been seen.

What’s next?

There’s going to be a Peter Hujar show at Fraenkel in San Francisco in January, and I’m writing an essay for the catalogue of that show. It’s called “Love and Lust,” and it includes kind of erotic material, but also pictures of couples. So, that’s actually my next writing.

What is it like looking back on his pictures now?

Ask me when I’m done. I’m always thinking about his work. I’m surrounded by his work. So, I need to stop and think about it in a way that’s actually useful.

Do you think there’s any lingering influence from beginning to understand photography through Peter’s work, which hinges on a human element?

Oh, definitely. But that was something I was interested in all along, that I was looking for already. But Peter certainly cemented that feeling, made it very real for me.

{ 3 comments }

What did Vince “pour” over the books? Honey?

Also, ’80s is written thus, not ‘80s or 80s. Your blog is not an Underwood typewriter.

What’s with all the snide copy editing notes you leave on blogs?

Somebody’s gotta know better. That somebody would be me.

Comments on this entry are closed.