Throughout December, we’re highlighting Paddy Johnson’s film and video reviews from The Reeler. This piece was originally published on November 14, 2006.

How many times do I have to read about the fact that Teri Horton, the owner of a Jackson Pollock painting with disputed authenticity, only has an eighth grade education? She may not have finished school, but there’s no way you would know that if director Harry Moses hadn’t chosen to emphasize this bit of biographical information in his new documentary Who the #$&% is Jackson Pollock? (opening Wednesday at IFC Center), a film about a retired truck driver who has dedicated the last 14 years of her life trying to get the presumed Jackson Pollock painting she bought for five dollars authenticated. It doesn’t help that virtually every writer in the country (barring dealer and blogger Edward Winkleman) is dutifully repeating the information as though it is of great relevance to a story that actually has less to do with class in America than it does with perhaps the biggest unwitting thrift store find in history.

But this is what happens when you let marketing tell you what a movie is about rather than just watching the film and figuring it out on your own. The narrative itself is set up by Horton, whose crassness is uniquely charming. “You ain’t going to believe this shit,” she says, launching into a story about how she haggled a second-hand store owner down from eight dollars to five for a painting she intended to give to her friend. Said friend rejected the work, and upon Horton’s attempt to unload the piece at a yard sale, an art teacher suggested she hold on to it because it might be valuable. “Who the fuck is Jackson Pollock?” Horton asks, thus christening Moses’ film.

The rest of the film recounts Horton’s struggle to enlist the help of galleries who she said wouldn’t give her the time of day because of who she is. In 2000, she sent the work to the International Foundation for Art Research for authentication; they returned it with a document stating they don’t believe the painting to be a Pollock. There is no evidence implying that this has anything to do with Teri’s education or profession, but that didn’t mean she was satisfied with their decision either; Horton responded by hiring forensic scientist Peter Paul Biro to investigate the painting and enlisted the help of dealer Tod Volpe, who, in addition to having clients the likes of Joel Silver and Jack Nicholson, was sentenced to two years in prison for fraud in the 90’s.

I suppose if anyone knows about corruption in the art world, it would be Volpe, but I doubt his name is carries any weight with figures such as Thomas Hoving, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not that this matters greatly, since it seems like there is virtually nothing that could have curtailed Hoving’s arrogance, who at one point declares “[Horton] knows nothing. I’m an expert. She’s not.” In fairness, however, had he heard the same fabricated provenance (the painting’s lineage of ownership) Horton unabashedly tells the audience earlier in the movie, this would undoubtedly inform his poor behavior (not that it excuses it). After all, Horton (left) openly admits that once it was clear that the painting’s lack of provenance was preventing her from getting her foot in the door, she began inventing a history which concludes with Pollock signing the painting with his cock. It’s a mystery, really, why the art world didn’t take the woman seriously.

I suppose if anyone knows about corruption in the art world, it would be Volpe, but I doubt his name is carries any weight with figures such as Thomas Hoving, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not that this matters greatly, since it seems like there is virtually nothing that could have curtailed Hoving’s arrogance, who at one point declares “[Horton] knows nothing. I’m an expert. She’s not.” In fairness, however, had he heard the same fabricated provenance (the painting’s lineage of ownership) Horton unabashedly tells the audience earlier in the movie, this would undoubtedly inform his poor behavior (not that it excuses it). After all, Horton (left) openly admits that once it was clear that the painting’s lack of provenance was preventing her from getting her foot in the door, she began inventing a history which concludes with Pollock signing the painting with his cock. It’s a mystery, really, why the art world didn’t take the woman seriously.

The point here, though, is not why Hoving won’t consider the painting, but why, now that new research has been produced by forensic scientist Peter Paul Biro, the International Foundation for Art Research won’t revisit its original finding that the work was not done by the hand of Jackson Pollock. This proves to be a more difficult answer than I suspect the filmmakers anticipated, because for all the evidence put forth in the movie — including finger print identification, matching paint samples and compelling comparative studies of similar Pollocks (and less compelling evidence, such as famous ex-forger John Myatt’s testimony that he couldn’t produce a painting as good as that himself; this is a man noted for such laughably bad forgeries as a Giacometti drawing featuring a male head on a female body), there are no statements made by the art world establishment.

I’m no Pollock expert myself, but I have worked at enough blue chip galleries over the years to learn a few things, and the first is that this matter is more complex than a film about “class” is ever going to be able to address. Of course, if you can’t get any of the leading authorities to speak with you on the authenticity of the painting, perhaps your filmmaking options are limited. I asked Moses about this, who told me it wasn’t for lack of trying. “We went to Eugene Thaw, who is one of the three or four top Pollock experts in the world,” the filmmaker said. “He would not give us an interview. We went to Francis O’Connor, who was right up there with Thaw.” Both men authored the four- volume Jackson Pollock catalogue raisonne (a complete inventory of the artist’s works) which means they have more first-hand knowledge of the artist’s paintings, drawings, and other ephemera than probably anyone else in the world. “They were on the board of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation,” Moses continued. “You may not know this, but they were evaluating which was a Pollock and which was not, and then they got sued so they passed it on to IFAR.”

Now, you can’t sue anyone for a wrong opinion — even if there is a fair amount of money attached to it, it is, after all, only his or her thoughts — but you can launch an antitrust suit if you believe that the organization is engaging in unethical business practice. Public court records indicate that the Pollock-Krasner Foundation has not defended a serious suit of this nature recently(which makes sense since they have been deferring to IFAR for nearly a decade), but you can see why they’ve passed the responsibility of authentication on to an outside source and why the art world is generally so reluctant to make a statement of any kind. Of course it would appear as though the foundation is not entirely out of the business: This past February they engaged in a rather messy public affair, using the work of Richard Taylor, a scientist who identified the artist’s drippings to be fractal, to dispute the authenticity of Pollocks owned by the son (Alex Matter) of friends of the artist. I contacted Taylor for comment on Horton’s piece, but have received no response. And Mike Bidlo, an artist with an excellent reputation for imitation Pollocks, simply expressed to me his disinterest in the legal squabbles surrounding Pollock authentication.

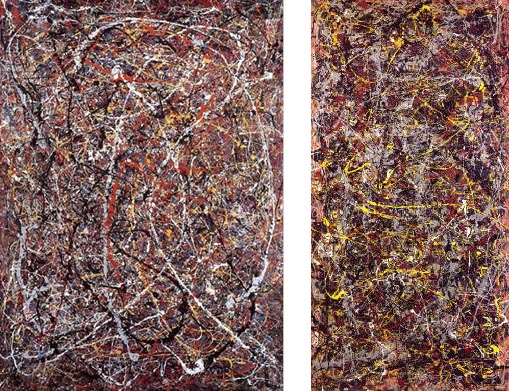

(L-R) Teri Horton’s disputed Pollock piece (66 3/4″ x 47 5/8″) alongside David Geffen’s Jackson Pollock No. 5 (48″ X 96″), which recently sold at auction for $140 million

Moses will tell you it doesn’t matter though, because the film isn’t about art anyway. “She could have just as well taken out a patent and invented something and because of who she is, couldn’t get anybody to see it,” he said. “I mean, I’m inventing that out of whole cloth, but that’s really what the movie is about. The movie is about this little person who is taking on the system.” But this conclusion has the feel of something that came to him after he realized he wasn’t going to get the interviews he needed to do the movie he intended in the first place. You can’t fault Moses for not being able to crack the art world elite, but it has to be said that if his intention was to reach those in the establishment (which on some level it has to be, since the movie will be a landmark if IFAR reconsiders its evaluation), then it has to be done on their terms.

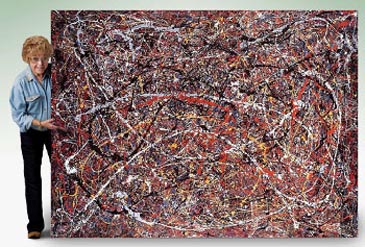

And I’m not sure he’s managed that. As someone who works in this field, I can tell you that all the forensic science in the world isn’t going to convince a fine art professional if he can’t come to the same conclusion based on what he sees. While it may seem a relatively minor point that throughout the movie the painting is displayed resting on an unattractive easel backed by a garish cinematic blue-gray light, I can guarantee you that the people Teri Horton, Harry Moses and Peter Paul Biro want to be taking this piece seriously don’t have anything to work with. For a film that by entertainment standards is a fine success, it will be an awful shame if the evaluation of the painting is held up because of lighting issues.

Comments on this entry are closed.