In New York, history gets remade quietly. That’s, to some extent, the nature of the city—whether it means the overnight formation of an arts district, or waking up one morning to hear that millions of books have been removed from the New York Public Library, as it happened one night back in March.

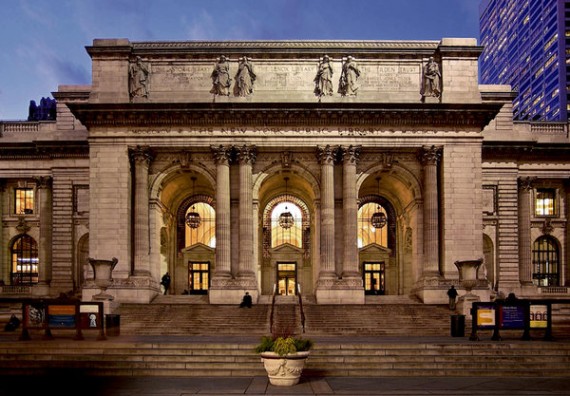

It’s also decided in New York Supreme courtrooms, where, on Tuesday morning, a mid-sized but rowdy group of scholars gathered to support two lawsuits against the Central Library Plan. This entails selling off two New York City libraries (Mid-Manhattan and SIBL) to developers, and consolidating them inside the iconic Stephen A. Schwarzman branch on 42nd Street. The plan also involves an extravagant, $300 million+ makeover of the Schwarzman building, tearing out the historic Carnegie Steel stacks and moving much of the rare book inventory to offsite storage, where they could be accessed by a circulating library system. Most of those books are already gone, to storage facilities in Princeton, New Jersey, and Dutchess County, New York.

Among the plaintiffs are Pulitzer Prize-winning authors, historians, architects. Defendants include the New York Public Library, the New York Parks Department, its head Veronica White, the city, and Mayor Bloomberg.

The case is one of many recent flashpoints in the rift between city developers and the public, which come down to dispute over simple facts.

One of the library’s main public arguments for doing this has been that the 42nd street branch’s historic stacks are deteriorating, and need to be saved by being moved to offsite storage.

There are other possible motives for the revamp. The Empire State Development Corporation would empty two libraries in prime Manhattan real estate.

“The stacks have been there for over a hundred years,” argued the plaintiffs’ lawyer Michael Hiller. “They moved the [books] out in anticipation of demolishing the stacks.”

“Now that we’re saying put the books back,” added Hiller, “they’re saying wait—as it turns out, the past hundred years there’s been a fire hazard here? With all due respect, that is absurd. There is a sprinkler system there.”

Michael Hiller, left at a rally with Citizens Defending Libraries (Image courtesy of Citizens Defending Libraries)

And as Hiller argued, storage facilities don’t necessarily keep books safe. “[I]f the city of New York is arguing that bringing all the books back to the stacks would be harmful to the books,” he said, “She’s making the point for us. Every time they move back and forth, it’s going to cause some harm. They should move back once.”

Even more troubling are the implications for researchers, who’ve argued that it’s impossible to know which books are needed, unless they’re readily accessible in New York. “Once those books are gone,” Hiller said, “They’re lost to history.”

It sounds melodramatic, but author (and plaintiff) Edmund Morris makes a strong case for the importance of the kind of “accidental discovery” he’s found at NYPL, while researching books about US Presidents. He describes following notes and clues to a century-old book:

And when the book is delivered, perhaps in fragile condition wrapped and tied with string, an old photograph may tumble out, tucked inside a hundred years ago by an anonymous person, and inscribed verso with a few copperplate words that reveal something hitherto unknown about both author and President.

It’s the kind of find that only happens after hours of careful hunting. And what if Morris hadn’t even known to request that book, but simply found it on a shelf? You can’t request a book from the circulating library if you don’t know it exists.

At the core, the case is a conflict of definitions of public space and historical value (made clear by the frequent snorts, laughter, and gasps from the audience). In reply, the library’s attorney Richard Leland argued that the plaintiff’s claims were “frivolous,” and that they are trying to unlawfully dictate the treatment of “books they don’t own.” (The audience gasped.)

Leland also unsuccessfully argued that the case is holding up construction. It’s not. As Justice Wooten eventually sussed out, the library won’t be ready to proceed for another few months, anyway, in which time the library will continue getting its permits in order. Leland then argued that the citizens are basically interfering with the project’s momentum.

“I’m prejudiced by the argument … by being forced into a position where the court is controlling the process in a case which I say should plainly be dismissed,” Leland said. “We would like to go forward. We have more than just these plaintiffs to represent in putting this project—putting this plan—together. To be hamstrung by plaintiffs who don’t have standing who are raising claims that are … legally insufficient and frivolous … I believe it’s backwards, your honor.”

As backwards as Leland finds the claims, the library has repeatedly anticipated such holdups. For example, the public only found out about the removal of the books after they were removed from the library, late one night in March. Often the defending lawyers would claim that information is “all on the website,” though plaintiffs claimed to have been ignored when requesting information from the Department of Buildings. Leland opened his counter-argument by handing out photocopies of a brand-new letter of resolution from the State Historic Preservation Office. The audience roared with laughter.

Justice Wooten chimed in. “You’re giving [Hiller] a very important penitentiary document at the core of the case, which he hasn’t seen.”

Later, Leland again tried to argue that the plaintiffs lacked sufficient evidence to put together a case.

“Your point is that they have to go by the information they have,” Wooten argued. “You’re arguing rightness, but how will the plaintiff know when the case will be right? If they don’t have information from the library, they don’t have information from you, they don’t have information from the Department of Buildings, how are they ever to know when the case becomes right? That’s their argument.”

Still, the case seems tenuous, given that the crux of plaintiffs’ argument is that the court must uphold a 1978 agreement between the city and library trustees. The agreement stipulates that the library’s trustees must act in the public’s interest, but it also grants them discretion in doing so.

Justice Wooten mentioned a few alternatives. “Aren’t the stacks landmarked?” he asked at one point. “Have you thought about trying this as a taxpayer lawsuit?”

I had to leave before the hearing for the second lawsuit, because like most people, I had to go back to work. When I left, the library agreed to a temporary restraining order until the facts of the case can be decided. In the end, they apparently agreed to wait to move forward until they get approval from the State Historic Preservation Office, which is legally necessary to proceed with demolition, anyway. Given that the head of that department, Veronica White, was named as a defendant in this case, I wonder whether that’ll be a problem.

UPDATE 12/20/2013: It’s important to note that the lawsuits aren’t the only impediment to the Central Library Plan; Bill de Blasio has voiced his opposition publicly.

{ 1 comment }

Now that Bill de Blasio is Mayor of New York 2014 wonder if the developers will stop the push of the backroom deals agreed with Bloomberg for development in that area.

Comments on this entry are closed.