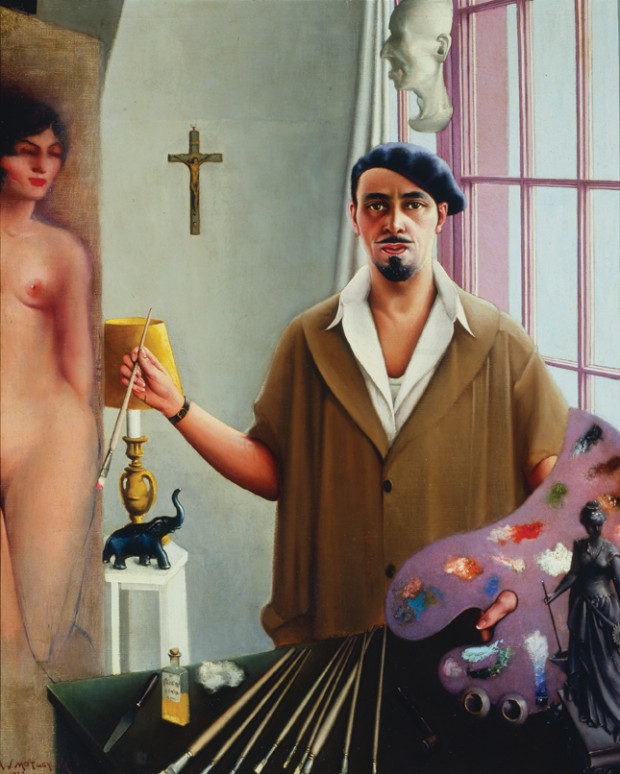

Archibald J. Motley Jr., Self-Portrait (Myself at Work), 1933. Oil on canvas, 57.125 x 45.25 inches (145.1 x 114.9 cm). Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne. Image courtesy of the Chicago History Museum, Chicago, Illinois. © Valerie Gerrard Browne.

“Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist” will soon reintroduce the world to a pretty engrossing oddball. Motley, once well-exhibited with the Harlem Renaissance, is generally known for his paintings of mid-20th century Chicago’s African American social scenes. But up close, theatrical streets and portraits are filled with fly-by-night stylistic changes, racy caricatures, loving tributes to women, fuzzy areas, abrupt compositions, psychedelic lighting, and out-of-this-world color choices. They’re fascinating.

Thanks to curator Richard J. Powell, the tight retrospective at Duke University’s Nasher Museum is brought to life with unusually good wall text and an extensive catalogue. (The show is set for a national tour). Roughly arranged chronologically from the 1920s to the 60s, the work is grouped by Motley’s family portraits, African American life from Chicago’s “Bronzeville” district to farmland, and trips to Paris and Mexico.

The opening painting “Self-Portrait (Myself at Work)” (1933) primes us for the grabbag of styles to come. A realistic portrait, Motley surrounds himself with Greco-Roman statuettes in front of his half-finished Impressionist portrait of a white nude. He himself looks like someone out of a Mexican muralist painting (though it’s unclear whether the style resemblance is simply because the worked-up paint has made sharper lines). The different references could read as straightforward identity politics, but then for some reason, he’s given himself delicate, feminine hands. Could be symbolic; could be because hands are just hard to paint from life. With claw-like thumbs and unarticulated fingers, hands seem to have been a challenge throughout.

Archibald J. Motley Jr., The Octoroon Girl, 1925. Oil on canvas, 38 x 30.25 inches (96.5 x 76.8 cm). Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, New York. © Valerie Gerrard Browne.

Slippery aesthetics run throughout all the early paintings, mostly of the women in his life. A hyper-detailed portrait of his grandmother Mending Socks, 1924, looks like what might happen if Whistler’s Mother were updated for the cover of Saturday Evening Post. On the other hand, he airbrushes sexual partners like his wife (who was white) to Kewpie Doll levels of smoothness.

As Amy M. Mooney points out in her catalogue essay, the twenties were a era for expanding beauty beyond whiteness, and Motley wanted to present a spectrum. Title terms include “mulatress”, (½ African American descent) “quadroon,” (¼ African American descent) and “octoroon” (⅛ African American descent). “[T]hey’re not all black, they’re not all, as they used to say years ago, high yellow, they’re not all brown,” he told Dennis Barrie in a 1978 interview. “I try to give each one of them character as individuals.” Motley, according to wall text, felt that “The Octoroon Girl” was one of the best pictures he’d ever painted. Objectively, the painting is a straight-on depiction of a girl looking vacantly beautiful, and by far the most conventional painting in the retrospective.

The rest of the show moves on to a more cartoony style, like a campy version of German Expressionism, which Motley seems to have developed around a 1929 trip to Paris on a Guggenheim grant. His Paris paintings– composed, colorful cafe and street scenes– are surprisingly stiff, with awkward people clumpings and smushy features. It’s like he was experiencing Paris life through a telescope. The distance isn’t surprising, considering Motley’s cavelike existence detailed in pages and pages in Olivier Meslay’s surprisingly unflattering catalogue essay, “Missed Opportunities”. “It proved possible to live on the same block as Man Ray, a few meters away from Braque, to pass Louis Aragon and Elsa Triolet every day on the street,” he writes, “and never to exchange so much as a word with any of them.” If you feel bad about binge-watching Netflix in your studio, it appears that even Golden Age painters squandered nightlife and networking opportunities. The man turned down a six-month grant extension from the Guggenheim!

The whole episode is interesting, because Motley presented a very different version of events to the Guggenheim, citing various new classical influences like Delacroix, Courbet, and Franz Hals, from mostly made-up trips to the Louvre. As he told reviewer Dennis Barrie again in 1978: “The biggest thing I ever wanted to do in art was paint like the old masters. There are no modern painters, with the exception possibly of George Bellows—none of them have ever influenced me.” (100-101) But Motley’s work looks nothing like Old Master paintings.

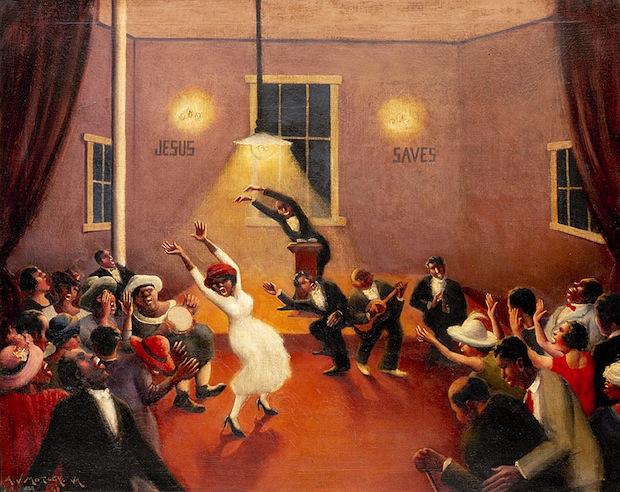

Archibald J. Motley Jr., Tongues (Holy Rollers), 1929. Oil on canvas, 29.25 x 36.125 inches (74.3 x 91.8 cm). Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne. Image courtesy of the Chicago History Museum, Chicago, Illinois. © Valerie Gerrard Browne.

The rest is filled with tropical-colored scenes, mostly of Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. Motley didn’t live in Bronzeville, but had grown up nearby in the mostly-white neighborhood of Englewood. The paintings could read as burning satire– the wailing mammies, screaming Holy Rollers, passed-out tourist, faceless whites– but the choices seem innocent. Of a group of men smoking and drinking in a pool hall, Motley remarked, “I used to sit there and study them, and I found that they had such a peculiar and wonderful sense of humor.”

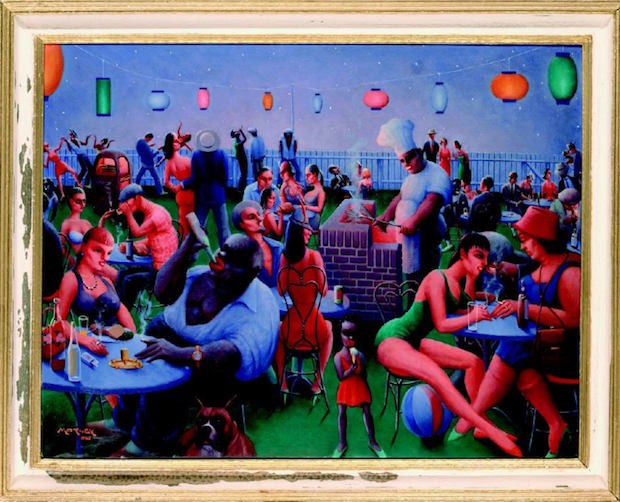

Archibald J. Motley Jr., Barbecue, 1960. Oil on canvas, 30.375 x 40 inches (77.2 x 101.6 cm). Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne. Image courtesy of the Chicago History Museum, Chicago, Illinois. © Valerie Gerrard Browne

The most bizarre picture of all is “Barbeque” (1960): a Southern scene of a mixed-race barbeque party against neon green grass. As is true of many of Motley’s paintings, grinning drinkers are lit from inside with an almost Hell-like glow. It’s beautiful, and strange, and makes it unclear whether this is a celebration of people having fun, or a cynically lurid depiction of hedonism. This sense of ambiguity echoes in a quote where Motley explains his understanding of identity, as it was being redefined by African American poets, musicians, and actors.

There is nothing borrowed, nothing copied, just an unravelling of the Negro soul. So why should the Negro painter, the Negro sculptor mimic that which the white man is doing, when he has such an enormous colossal field all of his own; portraying his people, historically, dramatically, but honestly? And who knows the Negro Race, the Negro Soul, the Negro Heart, better than himself?

So it feels accurate that Motley has described himself as, not Chicagoan, but just ‘peculiarly American’: belligerently independent, migratory, and full of contradictions.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 3 trackbacks }