In comic books, Modern art rarely makes an appearance. If it does, it’s usually seen as the backdrop to a crime—a museum heist, for instance. That’s what makes Grant Morrison’s “The Painting That Ate Paris,” a storyline running in DC Comics’ Doom Patrol, so rare; that comic took art and turned it into one of the most villainous creations ever known. In it, a painting swallows up entire cities. And with a weapon as rare as that, you may as well create an equally atypical group of supervillains—the Brotherhood of Dada—to take over the world with the help of this one ferocious painting. In the bonkers Doom Patrol-verse, this all makes sense.

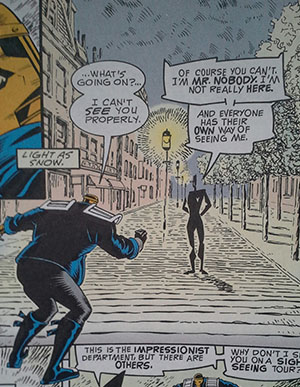

The comic starts off by introducing the Brotherhood of Dada, a ragtag group of villains led by Mr. Nobody, a self-proclaimed Dadaist who believes in an arty version of nihilism. Like Dada, he wants the world to be turned upside down. And like all good villains, Mr. Nobody wants to take over the world. That’s where the painting comes in.

It’s unclear how, exactly, people get sucked into the painting—if you’re close enough you get transported into it. If you recite a Dadaist poem, you’re transported, too. But what’s really interesting is how all this happens. Negative Man, one of the Doom Patrol members explains it as such:

It’s unclear how, exactly, people get sucked into the painting—if you’re close enough you get transported into it. If you recite a Dadaist poem, you’re transported, too. But what’s really interesting is how all this happens. Negative Man, one of the Doom Patrol members explains it as such:

“It’s activated by paradox modulation. Any contradictory ideas or images can be used to open a way into the painting.”

That’s a pretty basic metaphor for looking at a painting, evil or otherwise: open your mind to all sorts of viewpoints and you can “get into it.” But Mr. Nobody’s not going for improving everyone’s art appreciation skills. He just wants everyone to die. While throwing a throng of confused Parisians into the painting, he declares:

“Dada is useless, like everything else in life. And Dada has no pretensions, just as life should have none.”

Compare these lines to Tristan Tzara’s “Lecture on Dada” (1922). Mr. Nobody’s more than faithful to the original:

“Like everything in life, Dada is useless. Dada is without pretension, as life should be.”

For Mr. Nobody, the pinnacle of uselessness seems to be this oil-on-canvas, but there’s no such thing as pure uselessness in Dada. According to Tzara, Dada is one big “interlacing of opposites and of all contradictions.” Nothing could be more charming to a Dadaist like Mr. Nobody than turning that seemingly useless hulk of wood and canvas into a quite functional killing machine.

Outside the comic world, Dada never gave us artist-villains. There may have been talk about the value of chaos with Dadaists, but then real life stepped in. World War I caused these artists to hope for an anti-rationalism revolution; after years of facing the cold, cruel facts of death and war that stretched on for years, their hopes were dashed. In comics, just as soon as any cape-wearer wakes up in the morning, a war has already broken out. Heroes, mutants, and villains have gone numb to violence; death isn’t such a big deal. That’s why Dada was able to reach its end goal—not in art—but in comics reality.

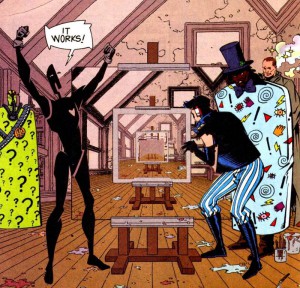

Now, the type of chaos sought by the Brotherhood of Dada was far more complicated than being a painting that eats people. As you can tell from the image, this small canvas is several levels deep, receding to infinity. Once inside the painting, nearly every level looks like Paris, but outfitted in a style from the Modernist canon: Surrealism, Russian Constructivism, Impressionism, and Futurism each have a world of their own. Watches melt on tree limbs, Cubist shards of buildings float mid-air, and fiery oranges and reds engulf the Fauvist sky. Unlike with Doom Patrol’s treatment of Dada, there’s not much in the way of constructing a worldview from these movements; they’re simply weapons in the painting’s arsenal, and they’re all terrifying.

Now, the type of chaos sought by the Brotherhood of Dada was far more complicated than being a painting that eats people. As you can tell from the image, this small canvas is several levels deep, receding to infinity. Once inside the painting, nearly every level looks like Paris, but outfitted in a style from the Modernist canon: Surrealism, Russian Constructivism, Impressionism, and Futurism each have a world of their own. Watches melt on tree limbs, Cubist shards of buildings float mid-air, and fiery oranges and reds engulf the Fauvist sky. Unlike with Doom Patrol’s treatment of Dada, there’s not much in the way of constructing a worldview from these movements; they’re simply weapons in the painting’s arsenal, and they’re all terrifying.

So what’s the point of making art into a more violent version of itself? There might be plenty of ways to answer this, but personally, I find it makes art into a humbling experience. Too often we see grace and beauty in art, even when another reaction might be more obvious. But with Doom Patrol, when art’s stretched out to its violent extremes, we get to see how utterly indecent art can be.

{ 1 comment }

Seems worth noting that this story was published in 1989. Back when there was still some semblance of arts education in American public schools.

Comments on this entry are closed.