The Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalist Exhibition: Lauren Adams, Kyle Bauer, Shannon Collis, Marley Dawson, Neil Feather, Kyle Tata, and Stewart Watson

The Walters Art Museum

Runs through August 17, 2014

What’s on view: The ninth edition of the Janet and Walter Sondheim Prize, a juried competition for artists living in the Baltimore region (including Washington, D.C. and parts of Virginia and Pennsylvania). Each finalist receives a $2,500 prize; the winner receives $25,000.

Oddly, most of the work falls squarely on a spectrum between “Calder’s Circus” kinetic sculpture and Fred Wilson’s “Mining the Museum.” It’s an strange grouping, but the result is that almost all of the work falls under an ordained form of institutional critique. Jurors are Claire Gilman (curator at The Drawing Center), Sarah Oppenheimer (New York-based artist), and Olivia Shao (New York-based artist and curator)

Corinna: I really like the idea of there being a large prize given out to artists just because. Minnesota has a similar prize given out through the Jerome Foundation. You know who doesn’t have this? New York. We have the Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss Prize, but that’s not for emerging artists.

Unfortunately, most of artists we saw at the finalist exhibition seemed to make work related to Modernist discourse: Marley Dawson’s minimalist, machine-made drawings, Neil Feather’s John Cage-inspired Rube Goldberg machines, and Kyle Tata’s cyanotypes and Mies van der Rohe-inspired photographs. Rather than an exhibition of the best work, it seemed like the judges had gone ahead and curated an exhibition. I was disappointed.

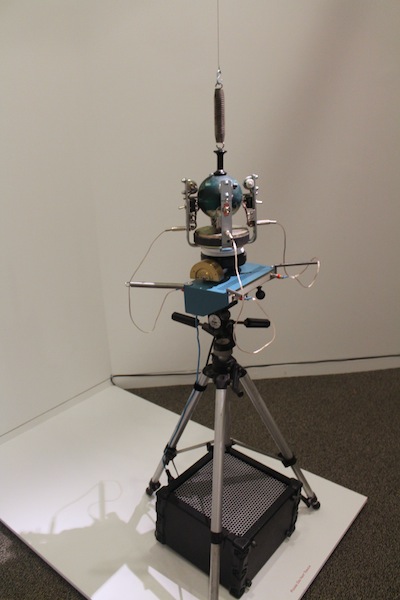

The winner ended up being Neil Feather. I can’t really say I know of another artist who uses a record player and a ping-pong balls to make audio work; he did stand out from the crowd of other finalists. Perhaps quirkiness and technical skill won over the judges.

Whitney: Kineticism did seem to be the main selection criteria. I heard somebody joke that the finalists were selected because of the official Artscape “Join the Movement” tagline; most of the finalists’ installations are literally movable-looking.

Feather’s stood out to me for his calculated use of tensions. In one long wooden contraption, a bowling ball dangles on a spring, with the wall text:

“Motor turns spring. Spring stores energy. Enough energy spins bowling ball. Dangling ball serves its purpose.”

This kind of logic was expressed in lots of varieties of vibrations, magnets, springs, and heavy balls. According to the wall text, Feather’s influenced both by Rube Goldberg machines and John Cage’s “Variations”, experimental compositions generated from simple geometric arrangement of lines, points, and axes. That’s interesting; it’s a bit of a paradox, to combine Goldberg’s futile-but-tightly-controlled logic with John Cage’s open formula for experimentation.

I’m not sure why Feather has chosen to combine those two ideas, though. While there’s more thinking here than the standard gallery stock, the results turn out to be pretty general.

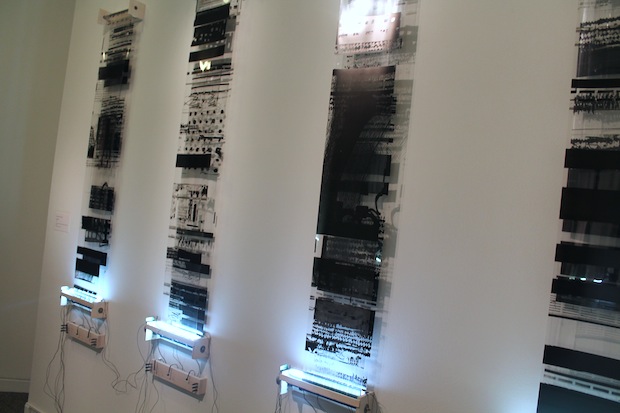

Shannon Collis’s drawing machines also draw from experimental sound history, this time from experimental composers Daphne Oram, Iannis Xenakis, and experimental filmmaker Oskar Fischinger. Wide, clear, wall-mounted rolling film strips covered in black drawings; when light is let through a clear part of the strips, it triggers little needles which make soft jingling sounds. It’s like a lie detector test sculpture, inspired by early graphical sound animations by people like Len Lye, Norman McLaren, and Harry Smith. Like experimental film, it’s kind of poetic. But again, like Feather’s, it’s not really poetry that expresses a mood or a point other than its own mechanics.

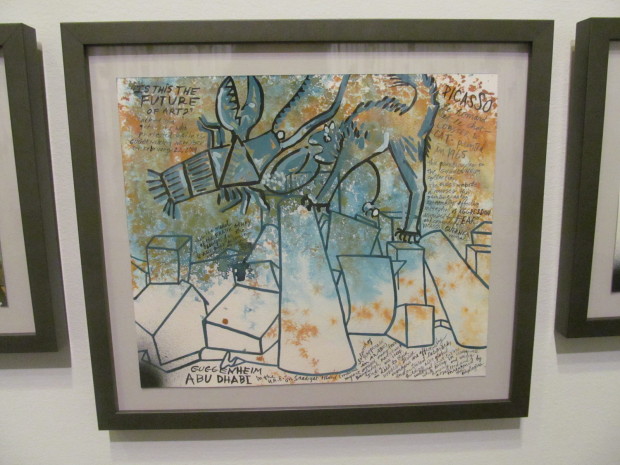

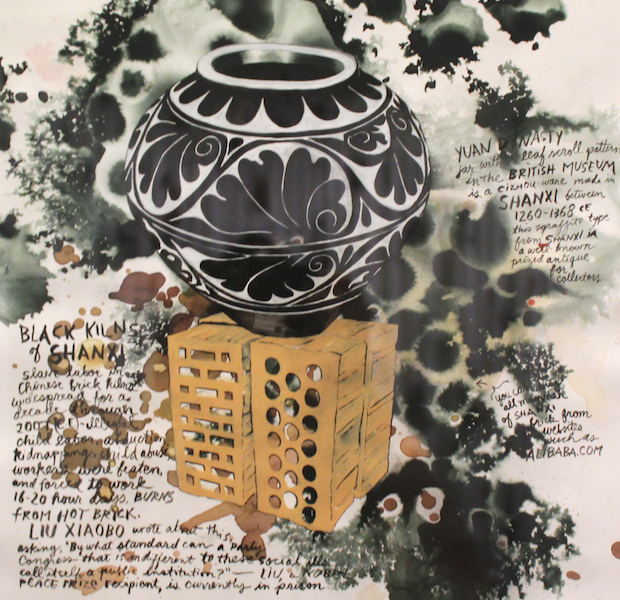

In a rare non-kinetic “Mining the Museum”-style exhibit, Lauren Frances Adams’s display easily offered the most to dig through, if simply because she’s dug through lots of material; the artist unearths slave history alongside contemporary slave stories in classical busts, paintings, and curtains. We learn, for example, that George Washington had a low opinion of the honesty and work ethic of his slaves; “Slave Killer Clubs” used painted wooden clubs to kill slaves at potlatch clubs; and in 2007, illegal Chinese brickyards tortured and enslaved children. And we’re all holding iPhones. The installation drove home the reminder that this isn’t some grim footnote in a history book, but continues to weave the fabric of everyday life. It made its point effectively, but again, tactics looked so familiar and polite that you could pass by without much thought. I wish that Adams would have made the issue inescapable.

Corinna: And it’s not that the work was bad—Kyle Tata’s work would feel right at home in any emerging art gallery the world over. But for the most the part (excluding Lauren Adams’s gouache paintings referencing Occupy), the work looked like it could’ve been 10, 20, or 30 years ago, as if nothing in the world has changed over the years. It has.

Stewart Watson’s “an indefatigable search for comfort,” an installation of family relics arranged as “potential disasters”

Comments on this entry are closed.