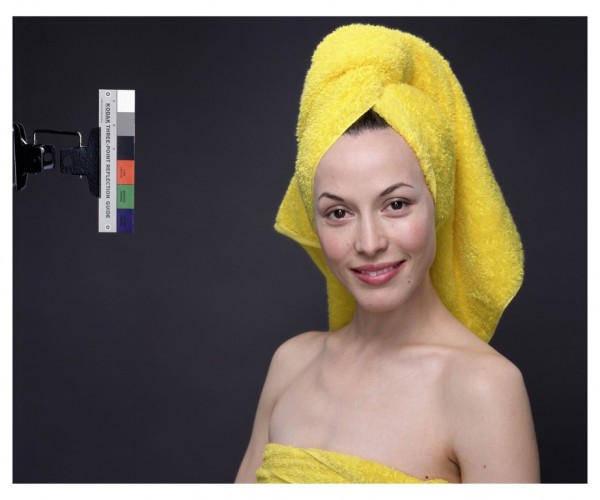

Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide, © 1968 Eastman Kodak Company, 1968. (Miko smiling), Vancouver, B.C., April 6, 2005, 2005. Image courtesy of David Zwirner Gallery.

Photographer Christopher Williams’s current retrospective at MoMA, Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, can feel a bit like he’s playing a trick on viewers. It’s a show that’s built around withholding information, meaning that what you see is rarely the whole story. When that trickery is successful, there’s usually some sort of reward for close-looking—a hidden detail or small clue that alters the photograph’s meaning and points to deeper complexities. However, what happens more often than not in Williams’s work is that so much is hidden from view that you just endlessly puzzle over the image before moving on.

In The Production Line of Happiness, the exhibition design itself is part of the art. Williams has done all he can to make sure that this show looks nothing like your standard retrospective: his high-production-value conceptual photographs are hung about a foot too low, and are neither ordered chronologically nor thematically. The effect of that is to confuse, with, for instance, an image of a Daniel Buren artwork placed next to a photograph of a shower door and an image of a red sock, with little that clearly connects them. If you want to find out more about these photographs, good luck—there are no wall labels.

Instead, any information about Williams’s photographs is buried inside a pamphlet that sets tiny black font against a dark red background, with columns and columns of text resembling a database printout. When you do find a work in the pamphlet, the titles are obnoxiously long; here’s an excerpt from a title for a photograph of a dishwasher:

Erratum

AGFA Color (oversaturated)

Camera: Robertson Process Model 31 580 Serial

#F97 – 116

Lens: Apo Nikkor 455 mm stopped down to f90

Lighting: 16,000 Watts Tungsten 3200 degrees Kelvin

Film: Kodak Plus-X Pan ASA 125

Kodak Pan Masking for contrast and color correction

There are 23 more lines after this.

To top it all off, Williams has put museum walls themselves on display: you’ll find cut-outs from the Art Institute of Chicago, fragments of walls from past MoMA shows, and the reconstruction of a 1958 Whitechapel Gallery wall—there are few hints, however, as to why.

All of those decisions are meant to infuriate you, as Williams wants this show to resist context and clear-cut meaning. If most retrospectives try to tie up an artist’s career into a coherent narrative, this one accomplishes the exact opposite. You encounter works with little sense of their background, why Williams might have made them, at what point in Williams’s life these were made, etc. This might be even more of an anti-retrospective than Maurizio Cattelan’s All.

Untitled (Study in Red) Dirk Schaper Studio, Berlin, April 30th, 2009, 2009. Image courtesy of David Zwirner Gallery.

It’s Williams’s later, studio-based work that shines in this show, because in them, Williams at once appropriates conventions and (subtly, though concisely) disrupts them. These works, mostly still-lives and portraiture, have the hyperreal gloss of magazine advertisements. But as generically familiar as these photographs are, there’s something slightly off to them. In “Untitled (Study in Red),” a model pulls a red sock over her foot. The photograph—beautifully made, but mostly unremarkable—would be right at home in a Uniqlo catalogue. It’s only after continued looking that you notice a healing blister on her ankle, breaking up the normally pristine world of advertisements.

That play between perfection and flaws continues in “Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide, © 1968 Eastman Kodak Company, 1968. (Miko smiling), Vancouver, B.C., April 6, 2005.” The photograph displays a woman wrapped in a bright yellow towel and posing for the camera. To her left, a “Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide” awkwardly juts into the frame. While guides like this are used to ensure the “correct” color in making prints, its very presence in the image throws the photograph’s composition. Coupled with the model’s subtle biting of her lip, this photograph feels like an off-kilter advertisement for nothing in particular. You start to wonder: are these just interventions by Williams, or are all ads full of these tiny (normally overlooked) flaws?

Williams’s best photographs are probably of cameras themselves, the single subject the artist returns to the most. Several works show cross-sections of camera bodies and hands gingerly touching a camera’s buttons. In one triptych, “Kiev 88, 4.6 lbs. (2.1 Kg), Manufacturer: Zavod Arsenal Factory, Kiev, Ukraine, Date of Production: 1983-87, Photography by the Douglas M. Parker Studio, Glendale, California, March 28, 2003, (No. 1-3),” a Kiev 88 camera hovers angelically amidst a white studio backdrop. The work is an ode to the sleek beauty of the camera’s design. In a show that’s otherwise light on emotional charge or physical contact, these photographs seem outright fetishistic.

Fig. 4: Changing the shutter speed, Exakta Varex IIa, 35 mm film SLR camera, Manufactured by Ihagee Kamerawerk Steenbergen & Co, Dresden, German Democratic Republic, Body serial no. 979625 (Production period: 1960–1963), Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar, 50mm f/2.8 lens, Manufactured by VEB Carl Zeiss Jena, Jena, German Democratic Republic, Serial no. 8034351 (Production period: 1967–1970), Model: Christoph Boland, Studio Thomas Borho, Oberkasseler Str. 39, Düsseldorf, Germany, June 19, 2012, 2012

Placed in the almost exact center of the galleries, “Kiev 88” begins to feel like the heart of the exhibition. After all, there’s something unique about the camera amongst Williams’ photographic subjects. While the camera is a mass-produced commodity, like many of the things Williams photographs, it’s the only object that also plays an active role in its consumption (through the creation of advertising imagery). Looking at this triptych, you begin to get a sense of just what exactly The Production Line of Happiness might refer to–it’s all somewhere entangled within the camera itself.

Other of Williams’s images have far less to offer, resisting even the most basic of interpretation. Take “Grande Dixance, Val de Dix, Switzerland, August 2, 1993 (No. 1-7)”, a group of seven images of a massive Swiss dam. Each photograph offers only a slightly differing view of the dam, but while some are more formally compelling than others, nothing sticks out about the group. The more you search for the same sort of cultural criticism that’s in Williams’s other works, the more you turn up empty-handed. These are photographs that prompt you to ask “why?”, but fail to offer even a semblance of an answer. That’s a question you’ll end up asking about many of The Production Line of Happiness’ photographs—why this jellyfish? Why these chocolate bars? Why this tire? To the show’s downfall, photographs like these, which do little more than leave the viewer confused, are the rule rather than the exception.

The exhibition, like Williams’s photographs, might itself have a key in the form of a grainy, black-and-white image of a curled-up dead beetle. The image looks like it could be ripped from the pages of a 1960s issue of National Geographic. A twist is buried in the work’s title, which tells us that the beetle is “Asbolus verrucosus,” or a “Death Feigning Beetle.” Meaning that in all likelihood, the beetle in this photograph isn’t actually dead, only pretending.

That act of feigning might be the conceptual core of Williams’s work. Williams wants to show us that, from the museum to ads to the camera itself, nothing is natural—in Williams’s view, even happiness has been assembled for us on the production line.

Williams’s strategy for revealing those constructs is never loud; instead, his practice is unassuming, more akin to subterfuge. He hides under familiar conventions (the advertising still-life, the museum retrospective) all while making minute changes to them, adding flaws and disrupting their original purpose. In individual images, that strategy works to great effect, giving you an uncanny sense of how mass-produced our daily lives are.

But as a show, The Production Line of Happiness just doesn’t add up. Williams’s reasoning is too hidden, his interventions too subtle. You know that a critique is being made, but you can’t quite figure out all the points. Which is a shame, because Williams undoubtedly has a lot to say—but without more clues to lead the viewer along the way, few are going to hear it.

Comments on this entry are closed.