“The story of twentieth century American art is already written—it is not a story about Chicago.” This opening line of Hairy Who & The Chicago Imagists situates Chicago art as a geographical “other,” placing regionalism at the forefront of viewers’ minds. Throughout the compelling documentary, the treatment of regionalism both reinforces the importance of place while challenging the pigeonholing that comes as a result of it. This film documents the history of Chicago’s most famous art movement that introduced the world to artists like Ed Paschke, Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, and Karl Wirsum, and brings to light the lasting effects of the city’s 1960s-era avant garde on contemporary practitioners. In short, you should watch the movie.

L-R: Karl Wirsum, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Suellen Rocca, Jim Nutt, 1967 (Photo by Charles Krejcsi)

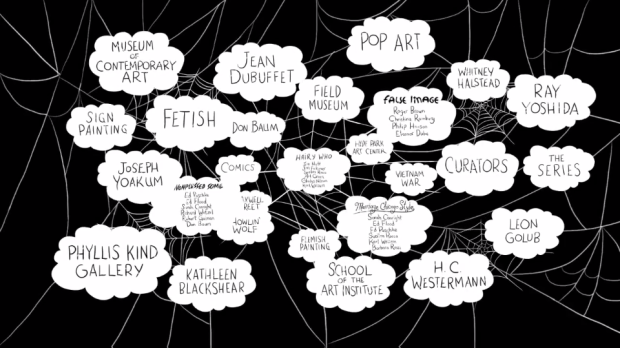

Directed by Leslie Buchbinder and written by John Corbett of Corbett vs. Dempsey (one of the main Chicago galleries representing Imagists artists and estates), Hairy Who tells the story of a group of School of the Art Institute of Chicago grads who made it big. Backed by a jazz-heavy soundtrack, animated vintage photographs, and drawn animations by Chicago artist Lilli Carré, the narrative outlines the figurative movement’s progression. This spans from “Hairy Who,” the first show curated by Don Baum in 1966 at the Hyde Park Art Center (HPAC), that would christen the name of this group of artists (Jim Nutt, Jim Falconer, Suellen Rocca, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, and Karl Wirsum), and the subsequent Imagist groups, Nonplussed Some (Ed Flood, Sarah Canright, Richard Wetzel, Robert Guinan, Ed Paschke, and Baum himself), and False Image (Roger Brown, Christina Ramberg, Philip Hanson, and Eleanor Dube), to the height of the artists’ international fame in the 70s and 80s with dealer Phyllis Kind.

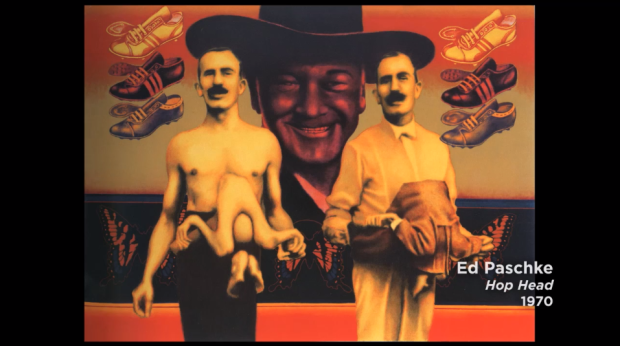

Mainly white but with an unusually large percentage of female members (the film names 7 women amongst 11 men officially included in those seminal HPAC exhibitions), the Imagists were known for bodies of work inspired by vernacular pop culture, though not in the cool, objective manner of New York’s contingent of Pop artists. These Chicagoans favored expressive, personalized approaches with pointed attention to craft, referencing everything from comic books and sideshow freaks, to psychosis, outsider art and surrealism, resulting in works that continue to be powerfully weird even by today’s standards.

While the narration of Hairy Who & The Chicago Imagists thankfully does not dedicate a lot of time outright comparing the importance of Chicagoans to their better-known peers from New York and Los Angeles, the doc features interviews from plenty of famous coastal artists. This helps illustrate how far-reaching the influence is of these “artists’ artists.” West coasters like Aaron Curry chime in about the impact of the Imagists on their own practices; from the East coast, Amy Sillman offers a historical note about how the cool conceptualism of the 1980s rejected the Imagists, their exuberance, and surrealism. They were regarded as very uncool. This perception lingers in Chicago today despite the fact that figurative painting regained popularity again in New York in the 80s, and that many of the artists taught and influenced by the Imagists have built wildly popular careers, Peter Doig and Jeff Koons amongst them. Koons shows up quite a bit in the film to say not much other than a cute anecdote about watching pregnant, tattooed dancers with Ed Paschke.

While the narration of Hairy Who & The Chicago Imagists thankfully does not dedicate a lot of time outright comparing the importance of Chicagoans to their better-known peers from New York and Los Angeles, the doc features interviews from plenty of famous coastal artists. This helps illustrate how far-reaching the influence is of these “artists’ artists.” West coasters like Aaron Curry chime in about the impact of the Imagists on their own practices; from the East coast, Amy Sillman offers a historical note about how the cool conceptualism of the 1980s rejected the Imagists, their exuberance, and surrealism. They were regarded as very uncool. This perception lingers in Chicago today despite the fact that figurative painting regained popularity again in New York in the 80s, and that many of the artists taught and influenced by the Imagists have built wildly popular careers, Peter Doig and Jeff Koons amongst them. Koons shows up quite a bit in the film to say not much other than a cute anecdote about watching pregnant, tattooed dancers with Ed Paschke.

Providing some of the clearest perspective on the presence of the Imagist legacy in artist history is Chicagoan Kerry James Marshall, who points out that while this type of art has fallen out of critical favor, the quality and significance of the works created then are still just as strong. He reminds us, “Ed Paschke has never not been an important artist.”

While the doc abbreviates the height of the international market for the Imagists in the 1970s and early 80s, it doesn’t end with the dissolution of the heyday. At this point in the film, Phyllis Kind gets accolades for her highly successful efforts in promoting the Chicago Imagists, while several artists express regret for all of the Imagists having been represented as a group by a single dealer for so long. Kind and local curators knew that marketing the Imagists as a regional group was doing an injustice to the individuality of these varying practices; it happened anyway as the work passed through the hands of outside curators, like Walter Hopps. Kind recalls a dispute with Hopps over this very issue, in which he explained, “Phyllis, none of the Pop artists wanted to be called ‘Pop.’ It has to happen. You show the work in a group context, and within 10 years, you’ll be able to take off one at a time.” This didn’t happen for the Imagists, though. Kind moved her gallery to New York, and eventually all of them were dropped or left the gallery, except for Wirsum.

Though Hairy Who & The Chicago Imagists opened with a broad case for regionalism, it closes with a look at the individuals. We see an aged Karl Wirsum plugging away in the studio, still using the same painted-encrusted wooden plank to keep the heel of his hand off the painting as he renders his impeccable edges. We follow Philip Hanson’s daily routine from the coffee shop for breakfast, onto the CTA bus, then to the studio, where he continues to churn out rich, graphic paintings at a steady clip. Of late, critical favor has been slowly coming around again for these two artists in particular, now in their 70s; Wirsum’s 2013 exhibition at New York’s Derek Eller Gallery was well received, and Hanson was included in the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Paschke was recently honored in Chicago with the opening of the Ed Paschke Art Center, and recently closed a nearly sold out show at Mary Boone gallery. However, much of the Imagists’ influence lives on through teaching, with Barbara Rossi, Nilsson, Hanson (retired last year), and Wirsum all still practicing artists and all on the faculty at SAIC—where they got their start in the first place.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 2 trackbacks }