Art subtly, but noticeably, frees up in a city where artists work less, live cheap, curate their own shows, and run their own spaces. I’m basing these assumptions on a superficial New York tourist’s perspective, of course, but from a month of studio visits in Philadelphia, I’ve found that performances seem to evolve onstage; ideas are passed around among friends; and whereas “networking” greases the wheels in New York, collaboration is the engine driving Philly’s artist-run spaces. Art isn’t just a career; it’s life. As Baltimore critic Michael Farley observed recently, “I feel like people go to New York to sell what they think they are; people come here to figure out who they are.” It feels a little like that in Philly, too.

This can mean that you’ll have fewer museum-readies and neat conceptual narratives; statements can be less defined, and, as one curator mentioned recently, smaller-town clubbiness can stifle innovation. On the other hand, if it’s a choice between that and a Brooklyn closet, I know where I’d rather be making art.

So without further ado, here are eight artists from Philadelphia who do it their way.

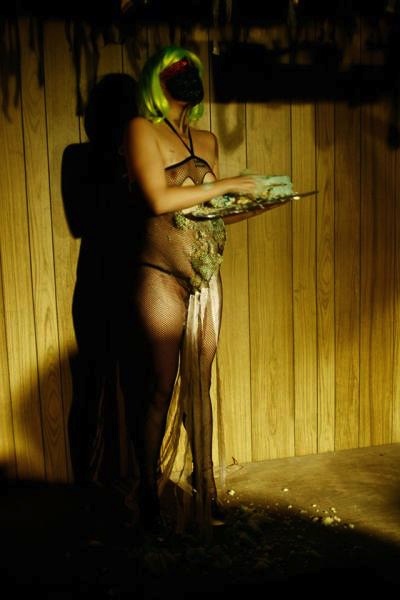

Eileen Doyle opens “Garbage World” with a rendition of “Que Sera Sera”, while stuffing cake down her fishnets. (Image courtesy of s+S Project tumblr)

Eileen Doyle, Garbage World

Uninspired by the 1970’s pedagogical conceptualism, and the dance-heavy Goat Island mode of performance, Eileen Doyle set out to create the opposite. And so, while attending The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) she founded the performance series, “Garbage World“.

“A lot of limitations were put on messiness,” she remembered of her undergrad. “Which I kind of wanted to delve into because the artists I look at are really messy, my friends are pretty gross. So the first one was in a mud basement in Chicago, which was fitting.”

Doyle’s been running Garbage World nights periodically in Chicago and Philly, since 2009. It’s a space where boundaries will be pushed, fearlessly, and no viewer gets bored; Doyle achieves this by MCing the evening in character as Gertie Garbage, wearing high heels, and stuffing donuts down the legs of her breastless fishnet bodysuit. All the while, Doyle makes sure everybody is in place for the performance.

“The person who’s going first can feel more pressure, and it can set the mood for the entire night,” Doyle told me. “Performers like it, because it makes it, like, yeah, okay, I’m gonna go for it. When there’s someone constantly doing weird shit, it’s a good motivator for people to kind of push things a little bit. It’s a way for me to be incredibly awkward, but have it be okay, in public, just to complement my own neuroses,” she said. “So sometimes I’m having a good day, sometimes it’s a bad day, but as Gertie Garbage, I can just do whatever. I don’t have to worry about stuttering, or jumbling words…it’s a mask for me to be myself.”

“Immediately, people who walk in and see me know, okay, we’re in for…something.”

In a sense, Garbage World’s freakiness is a tribute to life. Doyle started Garbage World a year after her sister was diagnosed with cancer; after intense chemo, and even enrolling in grad school in Austin, her sister’s health took another turn for the worse. She passed away in 2012. Doyle writes on her site:

There is something universal in our struggles with mortality. Artists give themselves the role as reality-producers and are ever-grasping for the meanings and workings of their worlds. Often, what comes is a world unto their own with its own definitions to be asserted. They are worlds of illusions to veil our vulnerabilities, but it’s necessary to form our illusions if we are to move through life not in quaking terror.

Inhibitions are left at the door: on any given night, you might find poop, stand up race comedy, knife fights, and golden deities. Let’s begin with Ishtar Bukkake (whose name is derived from Babylonian goddess of sex/death and a Japanese ritual sex act), a character created by the Chicago-based artist José Hernandez. In one performance, he created “The Stations of Ishtar Bukkake”, which involved anal play with hot dogs, and pooping in a bucket, all while wearing the finest sequined godlike robes. “So it was sacred-profane play,” Doyle reflected. “Garbage World was a place where these kinds of things could happen.”

Perhaps most representative of the series, though, is Mothergirl’s “Hair People”: a stand up comedy performance about race, but the jokes are told by a comedian whose body is primarily made of hair. When the jokes bomb, she shouts at the audience, “Come on, loosen up, folks, I thought you were all supposed to be a bunch of desperate weirdos!” But after a few too many self-deprecating hair jokes, another Hair Person heckles from the audience. “You don’t give a fuck about Hair People.”

“No. YOU don’t give a fuck about Hair People.”

The argument devolves into screaming and crying, about making jokes at your own expense for an ignorant crowd. But whether or not anybody gives a fuck about Hair People, both performers end up with pie on their faces.

Beth Heinly and Maureen Cummings

If you’ve ever been a teenage girl, then you know that it takes balls to publish your unedited high school journal. Nevertheless, fresh out of art school, Beth Heinly threw her inhibitions to the wind and published “The 3:00 Book”, a composition notebook full of comics she drew with her best friend Maureen Cummings. At around 220 pages, and with only 500 copies, the book has earned a bit of a cult status in the zine/comics world.

The book is a lot of what you’d expect: doodles and jokes about smoking pot, and doing it. One strip, “The First Time” basically consists of the punchline: “POP goes the weasel!” One recurring character, “Pumpkinhead”, is often depicted peeing gasoline on people and lighting them on fire.

Others are darker. “Mostly, it’s Maureen and I being assholes,” Heinly observed. “I’m pretty sure it got me banned from this Zine Fest.”

Heinly remembered one reading in particular. “As I was reading them aloud, I was like, “Oh, my God. This is actually really disturbing. There’s stuff in there about suicide.” We had a member of our school get cancer, and there are notes in there of me being like, I don’t care, she’s still a bitch. Really evil stuff. There’s an insert of Maureen saying I’m so starving, I feel like Ivan Denisovich– which is a book we were reading in high school about a Holocaust survivor.”

“It’s terrible,” she sighed. “That’s why I kind of like it, because it’s so honest in that way, and raw. I use it as inspiration for how I think about my art today, and when I think oh maybe I shouldn’t do that. Somebody’s gonna do it. I feel that way with performance art too. Performance art that I enjoy is really about testing boundaries.”

For example, Heinly and Cummings reunited for a Garbage World performance, “Girl Knife Fight”, a knife fight “ influenced by Actionism for snuff consumers” (per the YouTube description). Cummings and Heinly, wearing white Ts and tube socks, basically bitch each other out before stabbing each other to death.

“I really love collaborating and having girl friendship or kinship, so Maureen’s been good enough [to play along],” Heinly told me. “Even though she’s not into art or interested in being an artist, she’s my friend, and she has a creative side of her personality, and she’s kind of a muse to me.”

For Heinly, that kind of fucked-up humor shared between friends makes great fuel for art. Heinly also published a series of zines featuring drawings of SEPTA ads. The drawings identified bullshit messages– ads for suicide hotlines, food stamps, an AT&T ad mixed with birth control with tampon jokes. Backed by composition notebook paper, the work makes poverty feel like you’re being lectured to in a neverending high school detention session.

“I feel like when I went to art school I lost my sense of humor,” Heinly said. “After art school, part of my rebirth as an artist was rediscovering this funny part of myself.”

You can read Heinly’s comics weekly under “The 3:00 Book”, at theartblog.org. (And spend some time on her website and old archive, it’s amazing).

Sister Spaceship Gives Advice from Sister Spaceship on Vimeo.

Sister Spaceship: Angie Melchin and Kristen Mills

Given that most of the Philadelphia art community is run by artists, for artists, it comes as no surprise that studio visits frequently circle back to the idea of doing it yourself, or doing it yourself, collaboratively.

This came up on a Skype call recently with Kristen Mills, about her collaboration with Angie Melchin, as “Sister Spaceship”– episodic videos about two characters who man a spaceship, but whose attitudes command no authority. The two women perform as sort of spaceship pilots/talk show hosts on clumsy missions to, for example, dispense advice, and fix mechanical problems. In “Sister Spaceship Deals With Depression”, Angie’s character can’t afford her pills anymore, so Kristen’s has to make her a Bloody Mary. In “Sister Spaceship on Self Sufficiency”, Angie has to fix the ship, but Kristen keeps draining the battery when she uses the blender. They’re disheveled and a little spacey, but they manage every time.

“Angie and I…have a lot of similar understandings,” Mills reflected. “We both grew up in New England, and we both grew up very, very middle or low-class. So this kind of understanding of…your own tenacity to make something happen and to make something work. And how you understand the world.”

That sensibility can be found in Mills’ other collaboration, “Cloud Coffee”, a coffee truck which she operates with fellow Tyler MFA grad Matthew Craig. Fed up with working multiple jobs, cleaning houses, and running paper routes, the two friends started the business as a way of supporting their own artistic lives after school. From the truck, they’ve even started a juried annual cash competition for artists, with the ICA’s Anthony Elms as a recent guest judge.

“There’s a certain formlessness in Philly that I feel like Matthew and I were like, we can do it our way, we can create this how we want it to be,” Mills told me.

“I also see that space between artist and viewer as a similar space between producer and consumer,” she said. “And those are some of the issues that Sister Spaceship tries to deal with, as well, in their own fumbling kind of way.”

I emailed her later to ask what she meant by the similarities between consumption and art production. “The questioning that happens in both [Sister Spaceship and Cloud Coffee] hopefully instigates a revision of what art (and/or service) is, or where it is, or even more so – when it is,” she wrote back.

“I think it was Sue Hubbard who asked: Are we meant to deconstruct the shibboleths that underlie contemporary artistic practice, and question the accepted rules of how art should be made?

My answer is yes.”

Andrew Jeffrey Wright and The New Dreamz

Like many in Philadelphia, Andrew Jeffrey Wright cites Providence’s collective and music venue, Fort Thunder as a major influence. The warehouse-based collective, which ran from 1995-2001, has impacted a seemingly endless number of alt zines, colorful cartoons, printmaking (you can even find the stylistic sensibility on Cartoon Network). Wright is a direct product of that time—he spent a few years there as a young artist, before going on to co-found Space 1026, in 1997. When nearby collective Vox Populi guest-curated a show from Space 1026’s archives, which they felt defined them, they chose a Fort Thunder retrospective.

Like Beth Heinly, Wright takes particular delight in twisting mainstream advertising. This is evident in his early 2000s animations of flipping through the pages of a magazine; Wright and collaborator Clare E. Rojas used hand-drawn animation with Wite-out and marker to transform models into aliens, Bart Simpson, and Michelin-Man nudes.

Lately, Wright’s been performing as a collective with The New Dreamz; their “Fashion Show” series use what look like thrift store finds to transform themselves into a coked-up 80s fashion party, with twerking. Wright covers his rattail with a curtain of long blonde hair, and instantly, he takes on a kind of goddess power; with fans and mannequins, their expressions alternate from seduction to disinterest to fierceness. But their movements in general don’t quite target any particular fashion trope– just a sense of self-importance, like every movement is somehow more enjoyable, more significant, and revolutionary, than ours.

“I like when the shots linger too long,” Wright told me, “when you realize, what am I looking at?”

You can read Wright’s regular comic strip “Bananazz” weekly at theartblog.org.

To Party Too from Kristofer & William on Vimeo.

Will Haughery and Kris Harzinski

Are they a couple? The question is inevitably brought up about all male performance duos, like Gilbert and George, Andrew Andrew– and now, Will and Kris.

I didn’t ask, because I prefer not knowing. It makes their performances of mutual exchanges– like bros, playing out dom-sub scenarios, through the lens of instructional performance art– all the weirder. These scenarios range from the extreme, like “Surrender”, in which one of them plants a white flag in the other’s ass, to marital, like “To Party Too”, which involves a mutual rubbing of Crisco and Nutella on each other’s bodies, while simultaneously holding up opposing flags. Clothes are often mutually sliced off with kitchen knives. Spit is passed back and forth, in a variety of ways. The power tension immediately reminded me of AA Bronson and Nayland Blake’s kiss, but it seems more of a mass cultural critique than that; acts are all performed while wearing tightie whities, polo shirts, or nothing, in front of party streamers and pastel backgrounds.

This can get a little didactic– straight-faced, dead-on confessional acts seemed to make more sense for early video art, when there were pronouncements to be made, and an art constitution to be written. Now it’s a stock format.

Despite that, I’m not sure what the Constitution of Will and Kris is, exactly, and I think that’s the work’s best quality. Who’s in charge? What kind of a relationship is this? Is this a feminist or gay critique– and why would it have to be? With bro culture, the laws seem due for a rewrite.

{ 1 comment }

I grew up in Philadelphia, went to high school in the early 90s…. All any of us artist-types wanted to do was get the hell out of there, and I did, a long time ago. So it’s kind of weird to hear about Phila becoming this pulsating node of desire that people come to from elsewhere to figure out who they are or whatever….

Anyway.

OK so I’m not trying to troll, but am asking honestly, because I am interested and I would like to think they exist:

As long as you’re doing an overview of the scene, where are all the artists of color, not to mention of apparently any age besides 22-30 and from some other background besides an MFA?

Comments on this entry are closed.