Hardworking People from woodrow morris on Vimeo.

I first heard of the recent Goldsmiths graduate Woody Morris in 2011, when I watched Moseley Green: his documentary about a local artist who had assembled several random “woodstacks” (vertical piles of treetrunk segments) in Gloucestershire’s Forest of Dean, in what appeared to be an act of protest against the Forestry Commission, who had massacred the plot of land that he walked across daily. Even though it emerged that the local artist in question was making the woodstacks for aesthetic reasons, too, I thought it was an unusual example of how land art could be a powerful form of protest and identity, even on a small scale. Woody sent me a copy.

A few years down the line, Woody has emerged as a prominent figure in unpaid internship campaigning (see him dressed as Santa to protest about an unpaid role at The Serpentine here), and has continued to make documentaries, filtered through his informed political agenda, that shed light on small, underserved British community groups. For Woody, the two are linked, and his work seeks to reveal how.

Woody’s latest, Hardworking People, is a beautiful and insightful example of this. Using diptych frames to narrate an untold story and display relative archive footage simultaneously, the documentary follows little-covered 1986 protests by the Association of Island Communities against the Thatcher administration’s plans to regenerate the docklands area of east London. Following the closure of London’s docks that began in the ‘70s, Thatcher’s government viewed the docklands as post-industrial wasteland, and quickly established the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) in 1981 to provide a regenerative solution. Instead of working collaboratively with the local Isle of Dogs community (who were already suffering since the closure of the docks), the LDDC took away planning powers from the local authority and built the Canary Wharf banking district, which would displace the tight-knit communities and working class jobs that were already there.

After public outcry, rallies and protests, the local working class community are inevitably replaced with an upscale international banking district. Forced to give up on their local neighbourhood, the local community (a large percentage of which were dockworkers) reluctantly accept payouts that the government offer them, and move away. Nearing the age of retirement, and with skills no longer deemed valuable, it was the best chance that they had.

Following a solemn soundtrack of The Miners Hymns by Johann Johannson, a final shot follows former dockworkerand activist Brian Smith, who took a job in a London post room after the docks were closed. Unable to wrap his mind around an industry which doesn’t make anything but handle money, Smith muses about the perception that poor communities simply need to “work harder” in order to improve their economic conditions. “You talk about people working hard– you give ‘em a job and they’ll work hard. Why shouldn’t we be angry? Why shouldn’t we be radical?” It’s just one test case of the impact of globalisation on working people.

You cite that an unusual protest by The Association of Island Communities (AIC) became the starting point for making Hardworking People.

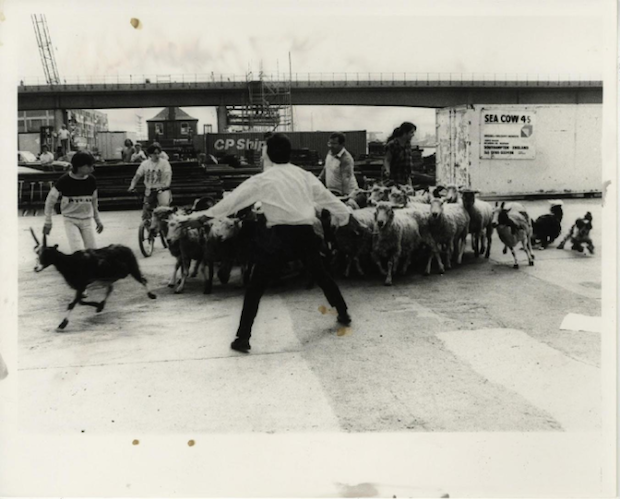

Yeah. It was 1986, and there was a ceremony to celebrate the symbolic first turning of soil for the Canary Wharf Development. Already by this point, various community groups represented by the AIC felt they were being ignored, and felt they were under threat from the developers. Essentially, they hijacked the proceedings using a herd of sheep and two beehives from the Mudchute Farm. It was a carefully planned protest. They chose their moment carefully, when the governor of the Bank of England was making a speech.

Association of Island Communities (AIC) protest at the turning of the first sod of the Canary Wharf Development proceedings, July 1986. Photo by Peter Dunne.

Was it this unusual mode of protest which made you want to make the film?

It certainly caught my eye. As a filmmaker, I am always looking for a starting point, or a way in. And this seemed like a perfect story, in a perfect place to make the kind of film I wanted to make.

I’m still struggling to get my head around the creativity of the AIC protests. The AIC as an organisation seems important—it was able to bring together various different community groups as well as activists and artists—the result was some pretty impressive protests [other stand-out examples include sailing down the Thames in boats with sails that read ‘Give Us Back Our Land’ and a funeral procession for the Isle of Dogs] That said, Canary Wharf was of course built, with the community not seeming to gain much from it. In that sense the protests ultimately failed.

So, the LDDC should have been putting money into local businesses, schools— investing in the community, basically, and instead they invested in banking giants like Barclays, Credit Suisse, and J.P Morgan?

Yeah, the closure of the docks ripped the heart out of the community, and the Canary Wharf development certainly didn’t replace it. When you think of the money that still kicks about in those towers…it could have been so different if the new financial district had been integrated with the community that was already there. Schools, youth clubs, leisure centres, community centres, local shops and pubs—all the things that make communities thrive.

Instead Canary Wharf was just plonked on the Isle of Dogs. The gated communities have only exacerbated the problem.

I can definitely see the influence or Jeremy Deller and Ken Loach in Hardworking People in its subject and style; you uncover a specific overlooked section of the British working class with a kind of Deller-esque poetry.

Yeah Jeremy Deller and Ken Loach are both important people for me. In Jeremy Deller’s project about the wrestler Adrian Street (So Many Ways to Hurt You, The Life and Times of Adrian Street, 2010), he has said that the photo of Adrian standing in front of his father’s mine in South Wales is the most important photograph of the 20th century, capturing the transition in the economy from industry to service. I would say that the photographs of the sheep hold the same power—depicting the final resistance of community and industry against globalisation and neo-liberal economics.

Tell us about the people that you met when making Hardworking People. Were they happy to share their stories with you?

The people I interviewed were all 50-years plus, and yet all in some way engaged with their community in a way that scarily doesn’t seem to be happening for our generation. People my age [25] just aren’t engaged with their local community in the same way, or even at all. Every time I met with people they would tell me a story about a different protest. I think the radical streak that revealed itself in the 80s is still very much present today.

[Ed note: The film unusually showcases blue collar workers in colorful communal protests, and adopting the language of radicals– taking control of their own fate. Notably, when the film closes with Brian Smith asking, “Why shouldn’t we be radical?”, it’s clear that Smith finds his own attitude to be out of step with the rest of the social strata].

Image of the “People’s Armada”, in which the AIC sailed up to the Thames Barrier and back to the Development Corporation’s offices. Photo by Mike Seaborne.

In Hardworking People, we’re given glimpses and hints into who the central figures of the AIC protests were through second-hand interviews and newspaper clippings. Throughout the documentary, Ted Johns keeps cropping up.

Yeah Ted Johns was one of the key figures of the AIC protests. He was a highly respected community organiser and central to much of what happened on the Island. He was responsible for an attempt in the 70s to declare the Isle of Dogs as an independent republic. There’s so much to uncover. My plan is to try and gain funding to continue my work on The Isle of Dogs. There are a number of ways that I want to continue the project, perhaps with 2016 being a focus as it will be 30 years since many of the AIC protests.

The footage you captured of Brian Smith—a docker who became a postroom worker in the when Canary Wharf was built— picking up debris from the beach at Newcastle Draw Dock is particularly hard to watch. It suggests that the (post-docker) banker generation have no regard or respect for the land that they are working on, its history, or the local community that it destroyed.

Brian is the person I spent most time with when making the film. Out of anyone that I met I would say that the changes that occurred on The Island have affected him most. He sees how those decisions back then have played out today and it hurts him.

Is that why you used the clip of George Osborne (Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer) making a speech in March this year about welfare changes and employment, at the beginning of the documentary? He keeps using the phrase ‘hard working jobs for hard working people’ without defining what “hard work” actually means.

Yeah George Osborne is a major culprit for using this divisive language. When I saw that he had made a speech at Tilbury Docks (where many dockers from East London moved to) I thought it would be a good clip to use. I think it’s important to be reminded of the contemporary situation we’re in: precarious work, zero hour contracts, demoralising temporary work. The focus and blame is shifted away from large scale corporate tax avoidance and placed firmly on the poor. The focus on benefit fraud is politically motivated, the phrase ‘hardworking people’ is an attempt to distract and divide. Most people on benefits are working people, having to supplement their income through the state because the minimum wage places people in poverty. I didn’t want to it to be a film about the 80s that didn’t relate to today. And that is something that struck me when making the film. The people that I filmed are all still critically engaged with the political situation of today, they care about the situation young people are in perhaps more so even than young people themselves.

Is that why you chose the title Hardworking People?

I had noticed the increasing use of the phrase by all of the major political parties: There are some people who aren’t working hard, and they are the problem; if you work hard we’ll support you. What that phrase doesn’t say is Britain loses substantially more through tax avoidance than through benefit fraud. The problem is not the poor, but the rich.

I hope people might begin to question what ‘hardworking people’ means. One of the main points of the film is to see the de-industrialisation of the 80s as a process that we have seen culminate in the precarious and ultimately limited work prospects of our generation. Zero-hour contracts are what we have now.

Some would say the docks died because they weren’t “flexible” enough to adapt. As Brian says in the film, his grandson goes to work on a Monday, at the end of the day they say, “Alright, we’ll see you Thursday.” Flexibility is everything today, which for many means flexibility to be fucked around.

Thanks Woody.

Comments on this entry are closed.