Alice Neel at David Zwirner. Install shot. Image courtesy: David Zwirner

How much can a portrait or landscape tell us about a person or a time period? A shocking amount, if the Alice Neel exhibition at David Zwirner, (open through Saturday), is any indication. The work chronicles Neel’s life in excruciating detail, communicating the way a detailed and intimate diary might.

The exhibition itself showcases 50 drawings and watercolors from 1927-1978. In the early days—the 20’s—sadness seems to define the work. A steely-orange watercolor of her Cuban-born husband Carlos Enríquez around the time of their daughter’s death shows him lost in thought. A minimally worked watercolor of an empty park in blues and grey feels deeply bleak. You don’t need to know that she lost a child to spot the devastation—it’s all over the paintings.

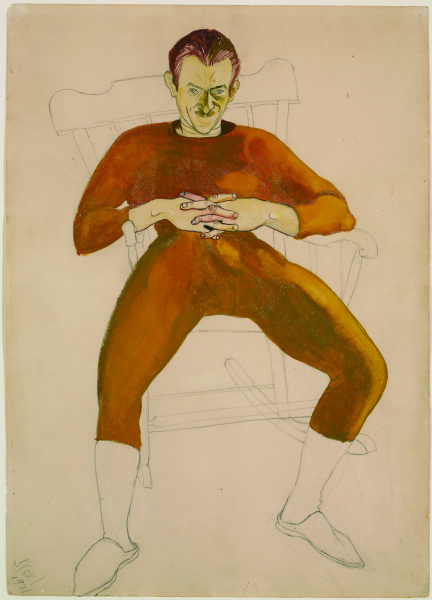

It’s images like these—parks, beaches, political rallies, and even illustrations for the Brothers Karmazov (1938)—that offer some respite from a show otherwise defined by portraits that expose the sitter in some way. Take, for example, her portraits of Kenneth Doolittle, a drug-addicted sailor who was also her lover. In one watercolor rendering, he sits in a rocking chair, smug, with his legs split open. He looks like the actor Sean Penn. In another piece, he sits hunched over, his eyes half open and his body withered. He’s pathetic, and Neel’s pen is unsparing.

Kenneth Doolittle, 1931

Watercolor and pencil on paper

14 x 10 inches (35.6 x 25.4 cm)

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Gift of Richard Neel, New York, NY, 1979

For me, those portraits were amongst the best in the show because they show people exactly as Neel sees them. And Neel is unusually perceptive—sensitive to both her own feelings and those of others. In a later self portrait-as-skull (1958) we see her eye bleed out and her teeth bared; her marriage with filmmaker Sam Brody had just fallen apart. Only a window separates the drawing from a heavily worked picture of Brody, executed around the same time. The marks fleshing out a shadow on his face are so dark you can hardly see him; it is as if he has emotionally retreated entirely and only his body remains. The contrast between the two figures couldn’t be more striking.

By the time we get to the 70’s some of that charge is gone. There’s less personal baggage on the line, and aside from a few angst-y pictures of her teenage daughter-in-law Ginny, many of the drawings feel more traditional. And perhaps that’s okay. After four decades of brutally raw portraits, sometimes a break is necessary.

Comments on this entry are closed.