Last fall, ahead of its centennial, the Baltimore Museum of Art reopened its grand front entrance. It’s a monumental hunk of building that looks a lot like what one imagines upon hearing the word “museum” (it was designed by John Russell Pope, architect of the Jefferson Memorial and National Gallery of Art). As a force of habit, I still use the more “modest” east entrance from the early 1980s, despite the fact that it feels a little like an airport terminal—complete with its taxi drop-off, concierge desk, bag check, gift shop, and cafe. It hadn’t occurred to me that I had never used the main entrance until I was standing in Sara VanDerBeek’s front room exhibition, a collection of photographic prints and sculptures that reference neoclassical architecture. Her body of work—a column, slabs, and images of marble—almost feels as if fragments of the museum’s facade had been transposed to the white box of the Contemporary Wing and arranged for inspection.

The exhibition, like much of VanDerBeek’s work, is intended to “reflect on the personal role of memory”—here, as it relates to the artist’s return to her hometown of Baltimore. These pieces feel slightly different, however, from other work of hers I’ve seen. VanDerBeek is known for limited-palette photographs of sculptural assemblages. They’ve always struck me as formally beautiful, but perhaps too sentimental and oddly empty at the same time. Here, rather than reducing a three-dimensional object to slick surface, photographic images of flat marble surfaces are treated as a sculptural material.

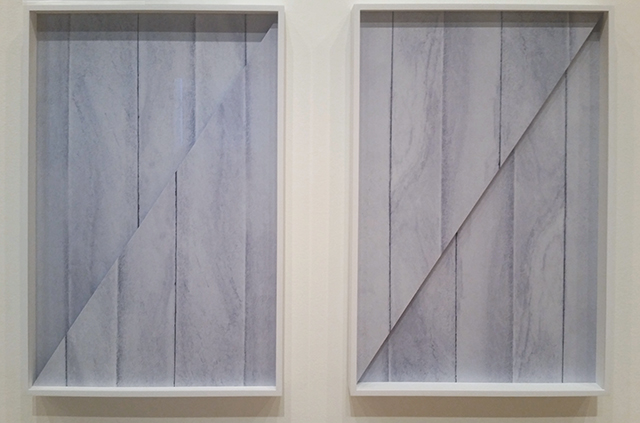

In “Threshold,” “Threshold II,” and “The Movement of Memory,” inverted prints of the same marble surfaces are shadowboxed to overlap. The creation of a physical depth between the two flat surfaces functions surprisingly well as a strategy to imply a sense of weight, materiality, or mystery to the prints; they can be read as both singular image and assemblage of physical objects. I found myself wondering where this particular slab of stone was located—VanDerBeek’s childhood home? The museum itself? An anonymous Baltimore rowhouse? What had it witnessed to accumulate its scars?

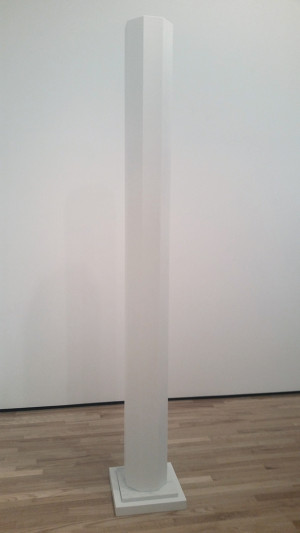

Sara VanDerBeek, Installation view

Conversely, a sculpture of a column in the corner stands in as an anonymous signifier of architecture, rather than a specific place. Collectively, the body of work floats in a strange limbo between minimalist sculpture and classical allusion. The exhibition almost makes too much sense for its context; somewhere between between idealistic “city beautiful” and crumbling ruins, the ivory tower of the institution, the civic, and—perhaps uniquely Baltimorean—the domestic.

As in many old cities dominated by pre-war architecture, marble features prominently in the Baltimore streetscape. But rather than serving as a material to be seen and signify grandeur—as in the banks of London, office lobbies of New York, subways of Moscow, or civic buildings of Washington—Baltimore’s marble exists on a humble, tactile scale. It’s touched, sat upon, and inhabited without much pomp in the city’s vernacular residential architecture. The marble stoop has long been the informal social space between the domestic and public; a butt-cooling front porch in a city where summers are hot and most buildings pre-date central air conditioning. Even in the city’s most notoriously post-apocalyptic-feeling neighborhoods—where dilapidated houses literally cost less than some high-end countertops—thresholds are decadently slathered with marble blocks. In Baltimore, the ubiquity of marble and stoop-sitting has created a sort of local semiotic inversion from “precious” to everyday.

That’s obviously the reference made by “Steps,” a string of marble blocks blended with paint to resemble a monolithic slab bisecting the gallery. But the piece is confusing. Its placement in the gallery and reference to row-house architecture could (and probably should) invite the viewer to sit down. But it has a frustratingly precious feeling. I almost wanted to ask if we were supposed to sit/walk on it, but I would’ve felt really embarrassed if not (even though there were tourists climbing all over two touch-friendly Franz West sculptures one room over). Instead, Steps comes across as a barrier between the gallery’s entrance and the work on the wall. Perhaps that’s the point. Then again, it could be that VanDerBeek—as in so much of her work—has reduced the object to an image of itself rather than the tactile, utilitarian thing it once was.

This, and a few other works, were exceptions in an otherwise satisfying show. “Orpheus,” another collage-like print, is a miss. The photos are of dancers at University of Maryland Baltimore County, where VanDerBeek’s father (experimental filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek) was a professor. But the inclusion of figures in this one piece feels arbitrary, especially when the body is reduced to decorative furniture—a jumble of legs treated as little more than a design motif in a composition.

Leaving the exhibition, I was inspired to use the BMA’s glamorous front door for the first time. Descending those steps back into the city, I was struck by what a nuanced take on site-specificity VanDerBeek’s work offers. She approaches the very building blocks of the universally-experienced built environment from an unapologetically personal perspective. Unexpectedly, I drew a connection to my experience of Victoria Fu’s recent work here at The Contemporary, where the artist’s video projections playfully interacted with one of the city’s few remaining pieces of Brutalist architecture. Both projects were refreshing to see in Baltimore, which—like many predominantly poor, predominantly minority cities—can often be a prime context for what feels like cultural carpetbagging. It’s easy for transient artist populations to tackle site-specificity by picking low-hanging, obvious fruit (race, income inequality, institutional critique) through didactic, often patronizing projects that fail to contribute anything substantive or original to an already ongoing discourse. But both recent exhibitions inhabited their sites with a gentle touch, gifting viewers space to draw their own conclusions rather than be force-fed content. It’s a courtesy not often afforded to audiences here enough.

{ 2 comments }

how do you think they carried that big marble log into that room without bumping into corners?

It was actually 5 separate stoop-sized pieces that are placed end to end.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }