One trend we identified at NADA was the ubiquity of paintings (noun) with a deliberate absence of painting (verb). Perhaps reactionary to provisional painting—and all its polarizing discourse on authorship, ego, and craft—there was nary an identifiable brushstroke on many of the fair’s plentiful canvases. Which isn’t to say that the work didn’t look painterly: paintings are an easy thing to bring to a fair and sell, but it seemed like no one wanted to paint. What we ended up with is a sampling of strategies to mitigate, or negate entirely, the apparent hand of the artist from the process of mark-making.

While this might not be a brand-new trend, it’s worth noting a zeitgeist: most of the painters showing at NADA deal less with the realm of the image and more with the construction and deconstruction of surface. Painting’s new use seems to be as an index of abrasions: grinding, smearing, soaking, and staining. It seems like an oddly old discussion for 2015, but it’s apparently the one we are having. And it’s surprising how many artists have managed to make ontological fussing seem relevant again.

The most extreme example of this trend was a pair of “paintings” by Michael Manning at the Smart Objects booth. The pieces were fabricated with a 3D printer that constructed brushstrokes, drips, and spray-paint marks by adding successive layers of texture and pigment. They look exactly like the squiggly pastel paintings one might’ve seen making the rounds on tumblr or fairs like NADA in recent years. Manning’s work seems to suggest that one could seamlessly produce an authorless physical commodity out of the ether of social media in much the same way the artwork present at the fairs is endlessly photographed, reblogged, and copied across the digital world.

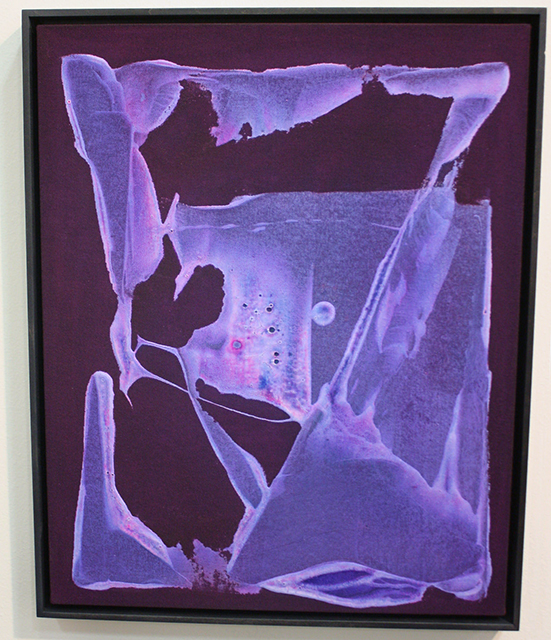

Across the fair, at ltd los angeles’s booth, Seth Adelsberger’s “paintings” are conversely visceral surfaces designed to read as sleek digital abstractions when photographed and disseminated on the net. They are, again, produced without a brush—Adelsberger sloshes gesso across canvas with a squeegie and then submerges the canvas in dye. The result is a gradient effect mapping the topography of the surface.

Even in the standout, painterly figurative work by Genieve Figgis at Half Gallery (currently blowing up Instagram), singular brushstrokes are almost entirely absent. The artist allows puddles of watery acrylics to coagulate, marbleize, and ooze across her paintings. The end result is a barely legible image that’s authored equally by Figgis’s hand and the chance movements of fluids. They’re gorgeous and are totally the show-stoppers at NADA—literally—we spent several minutes transfixed by them—an eternity in art-fair time.

We’re not entirely sure why brush strokes are suddenly so rare. Maybe everyone is just bored with them? Afraid of their capacity to read as either flippant or declarative? Tired of washing brushes? But it seems like we need a new vocabulary for describing two-dimensional work. When I asked Andrew Laumann, who has several works in Springsteen‘s booth, to define his medium he replied: “Painting… They’re collaged together but I consider them painting?”

Shawn Kuruneru at David Peterson Gallery. Of all the brush-less paintings, these kind of seemed like a miss.

Joe Reihsen at The Hole. In real life, this smeary (pallet knife?) painting (Right) plays some of the same optical tricks as Seth Adelsberger’s paintings. Sadly, it’s not as photogenic.

Dustin Pevey at Bill Brady. I saw a whole show of these in Miami during Basel and like them more as a huge series. They strike me as contemporary wallpaper comprised of everything that’s been trendy in visual culture in the past few years: normcore logos, digital images mixing with provisional painting, and plenty of the collage and alternative-painting-making techniques that characterized this fair. When it’s all combined, it implies that the aesthetic signifiers of “relevance” tend to reduce content to mere decoration.

Comments on this entry are closed.