Donald Trump wants to build a wall to keep out the Mexicans. Now, Scott Walker wants one to keep out the Canadians. If contemporary American political ambitions are starting to resemble policies out of the Ming Dynasty, it begs the question: who are the Mongol raiders they’re so afraid of? From memes depicting Syrian refugees as terrorists to the urgency of the #iftheygunnedmedown movement, it seems like the (conservative) white Western world’s recent representations of “the other” are fraught with paranoia, militancy, and old-school racism that’s thinly veiled as fear.

This leaves many artists in a fertile, but complicated place. Performing expectations of “otherness” has historically been a tried-and-tested strategy for subversion in identity-informed art, often with costume. But as the the dominant media portrayal of “the other” becomes increasingly militant and threatening—from domestic rioter to foreign zealot—artists responding to it are handed a pretty bleak palette. For artists looking to dress the part, this season’s must-have accessory is an AK 47.

Last week, two multi-media exhibitions opened within the space of two days, each showcasing artists enacting the roles of rebels, stateless militias, and ambiguous terrorists. In #blacktivist at the Goethe Institut’s Ludlow 38 Curatorial Residencies, German video artist Mario Pfeifer collaborated with director Drew Arnold and political rap group Flatbush ZOMBIES on a two-channel video installation that mashes up the Black Lives Matter movement with visual language from “rebel” groups across the political spectrum’s fringes. In The Accidental Pursuit of the Stateless, at BravinLee programs, Elektra KB asserts herself and a cohort of masked migrant women as esoteric soldiers—performing in videos and photographs presented alongside a variety of art objects that take design cues from both the aesthetics of the state and those oppressed by it.

One screen of #blacktivist is a Flatbush ZOMBIES music video, which begins by subverting the conspicuous-consumption tropes of commercial hip-hop imagery: a close-up on what appears to be a “blingy” diamond ring pans out to reveal a set of jewel encrusted handcuffs. From there, the violence of the imagery intensifies to news coverage of police brutality and ultimately, footage modelled on ISIS videos. The video ends with the group—Erick Arc Elliott, Meechy Darko, and Zombie Juice—posing as masked militants in front of a black-and-white banner that’s a combination of the Confederate battle flag and the iconic Islamic State logo. They’re preparing to decapitate a kneeling, hooded figure. When they remove the hood, their victim is revealed as a President Obama look-a-like.

The message behind the loaded imagery is unclear, but it lends itself to several timely interpretations. The black artists could be assuming the role of white supremacists who have repeatedly stymied the efforts of the relatively progressive Obama administration, and comparing those efforts to the violence perpetrated by ISIS. It could also be seen as an exasperated expression of frustration with the utter failure of the US government in regards to its black citizens. Here, perhaps any and all symbols of rebellion against the American hegemony are up for grabs as stand-ins to communicate rage. The battle flag is raised, no matter the direction it’s blowing. Then again, the scene might be a parody of the mainstream media’s paranoid depictions of marginalized groups—from casting Black Lives Matter protesters as “thugs” to CNN’s comic over-reaction to the sight of a dildo-covered ISIS flag at a gay pride event. Pfiefer states his “work explores representational structures and conventions in the medium of film.” As such, the inability of a moving image to convey a singular, fixed meaning is undoubtedly part of the medium’s appeal.

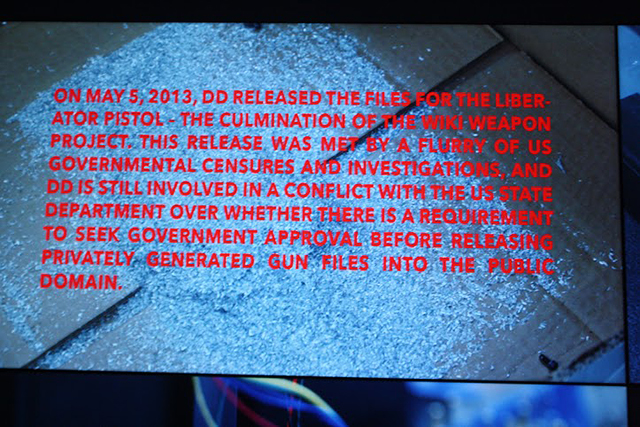

That implosion of right-wing aesthetics with leftist concerns is inverted in a second, documentary-like video. It has a vaguely cyberpunk tone, with the Flatbush ZOMBIES discussing race/class inequality, redistributing the means of production, and footage of 3D printers. The scrolling text, however, informs the viewer that the machines are fabricating open-source assault weapons. Defending the 2nd Amendment is repeatedly referenced in the text—a political concern almost exclusively associated with extreme conservatism and the white libertarian movement. I left unsure if the piece was intended as a rallying cry for oppressed groups to adopt the tactics of right-wing militias and arm themselves against a hostile state, or merely as a display of the escalating animosity against the American government from every corner of the socio-political arena. Either way, the video was deeply unsettling. While watching the short piece loop several times, I found myself performing acts of mental gymnastics in an effort to resist associating anti-gun control activism (which tends to have extremely racist overtones) with the social justice movements I’ve always trusted as benevolent and pacifist at heart.

![Elektra KB, "Undoing Gender Beings of T.R.O.G." 2014. [Note: T.R.O.G. refers to "The Republic of Gaia" an allegorical feminist nation-state within Elekta KB's mythology where the constructs of gender, class, race, national identity, and religion are battled, negated, and remixed. ]](http://artfcity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/undoing-beings.jpg)

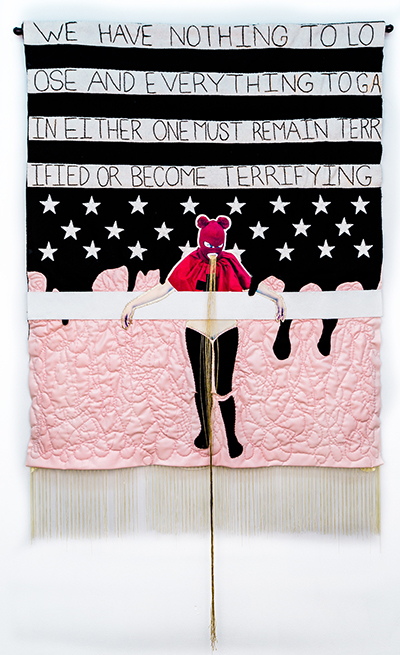

Elektra KB, “Undoing Gender Beings of T.R.O.G.” 2014. [Note: T.R.O.G. refers to “The Republic of Gaia” an allegorical feminist nation-state within Elekta KB’s mythology where the constructs of gender, class, race, national identity, and religion are battled, negated, and remixed. ]

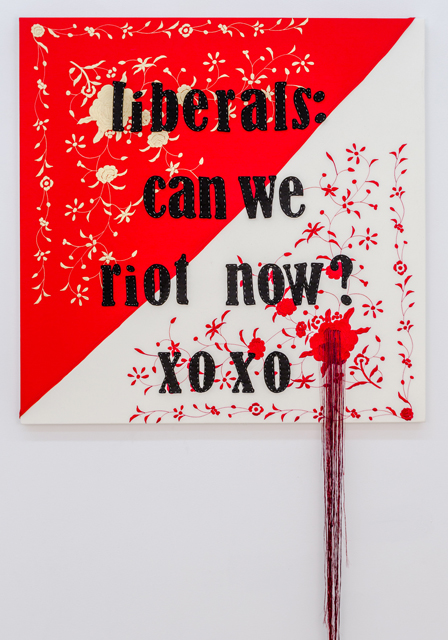

Far from the cold sleekness of the 3D-printed gun and polished video, KB’s work presents an alternate take on DIY production as a rallying cry for resistance. In xerox prints, hand-embellished fiber pieces with titles such as “The Otherness” and “Spatial and Gender Migration”, and endearingly guerilla videos; her craftsmanship is visible in an impressive array of media carried out with a somewhat anarcho-punk design ethos. These works feature unlikely combinations of pre-Columbian architecture, ominous female figures, and militant aesthetics that flirt between fascist and rebellious.

In “The Accidental Pursuit of the Stateless,” the exhibition’s eponymous video, masked immigrant women make their way through a German supermarket. Paradoxically, their strange costumes lend the women visibility and anonymity at the same time—granting them the attention it’s implied they aren’t given while removing them from the gazes of the male and surveillance state alike. This cuts to a video collage pantheon of female figures: nuns wearing inverted crosses, strangely-hooded soldier figures, and others that resist easy identification as any given archetype. Later, they dance on Central American pyramids while holding automatic weapons. A fleet of UFOs flies above them. It’s a totalizing vision of threatening otherness—simultaneously mocking the fear of the “illegal alien” while ominously bringing to mind the Jean Genet quote “The arrogance of the strong will be met with the violence of the weak.”That’s a warning the world should probably take to heart.

![From Elektra KB, "The Accidental Pursuit of the Stateless," 2015. [Installation view]](http://artfcity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/IMG_6974.jpg)

Comments on this entry are closed.