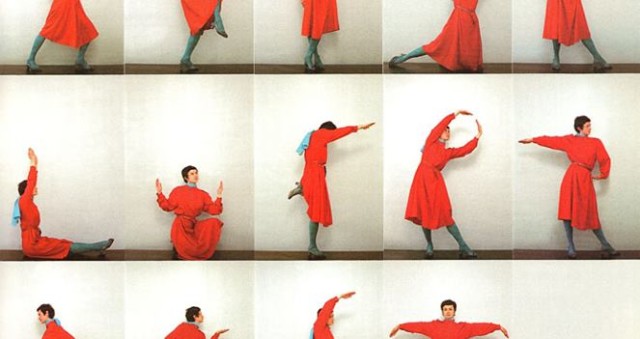

Paulina Olowska, “Alphabet,” 2005/12. From the Claire Bishop talk, “Déjà Vu: Contemporary Art and the Ghosts of Modernity”

Going to lectures where the speakers workshop their book on you sucks. This was the case last Wednesday evening, when a crowd of artists, students and academics packed an OCAD auditorium for “Déjà Vu: Contemporary Art and the Ghosts of Modernity”, a free public lecture by art historian Claire Bishop.

Bishop, currently a professor at CUNY, is best known for her take down on relational aesthetics and participatory art in Artificial Hells, as well as a much-debated 2012 Artforum essay about new media’s place in mainstream art. So when she gave a talk missing powerpoint slides and acknowledged that she was still developing her ideas, it was at first a bit refreshing. Even the best of us have to work out our thoughts and even if the ideas weren’t totally fleshed out, there was a lot to think about. But the novelty wore off quickly. She hadn’t even figured out an ending for her talk.

From what I could gather during the lecture, Bishop believes we’re stuck in a rut she describes as ’“reformatted modernism”. The self-invented term refers to a historicist strain of contemporary art, where our downloadable obsessions with Eames chairs, van der Rohe skyscrapers and archival forms of display (think slide projectors) have rendered Modernist references in art that are all image and no function.

Bishop easily supported this core idea. Take Vladimir Tatlin’s “Monument to the Third International” (1919), a frequently-referenced work Bishop sees as a “telling lens of the changing relationship to utopian Modernism in contemporary art.” The Constructivist twin helix tower was a post-Bolshevik Revolution utopian design aspiring to unseat the Eiffel Tower as the symbol of modernity. Tatlin’s Tower, however, was never built—Tatlin was more an artist than architect, and the Tower never went beyond the design stages.

Nonetheless, the monument has been quoted in dozens of art works. While Dan Flavin endeavored to memorialize Tatlin’s Tower in his “Monuments to Tatlin” series (1964-1982) as a postmodern joke—he used fluorescent tubing to realize a monumental sculpture of traditional grandeur—later reformatted Modernism quotations have been tinged with nostalgia. According to Bishop, works like Ai Weiwei’s “Working Progress (Foundation of Light)” (2007) or Michel Aubrey’s “Monument to the Third International Set to Music” (2008) are faithful, even awestruck reconstructions of an avant-garde memory. “The impossible beauty of revolutionary design”, in Bishop’s view, has become a reverential symbol of “failed artistic utopianism.”

Mark Lewis, “Above and Below the Minhocao”, 2014, film still

This type of interpretative connect-the-dot art historical analysis bore fruit in the sense that it also lead Bishop to point out regional variations informed by the geopolitics of those areas. Brazil, for instance, had a far different relationship with its Modernist architecture, given that many of their buildings were of an international style ported over by star European architects in the 1930s. In this case, the architecture became an empty formalist structure requiring clean lines and sharp angles that allowed the rich owners to remove any indigenous references that might remind them of the working class. (Bishop refers to this as “aesthetic cleansing”) In the 1990s another version of this aesthetic phenomenon: the city’s architecture began looming largely in the work of visiting North American and European artists: she cited Mark Lewis’s “Above and Below the Minhocao”, where a distant single camera shot pans over an elevated motorway in Sao Paolo, and in looking back revels in its ruin and disuse, while also affirming modernism’s stature. Nostalgia for the past almost implicitly signals a yearning for “better times”. At one point, in connecting artists’ reformatted Modernism fixations with the worldwide increase of PhD programs, Bishop expressed a fatigue for art practices “sublimated with research”: while the artists of her generation were “intelligent”, the “topics of their research was more fascinating than their work.”

As it became clear that Bishop’s selective reformatted Modernism grand narrative would be the talk’s dominant form of inquiry, the lecture began to feel like an epic long read of a Totally Looks Like meme of market-friendly biennale-baiting art.

In some ways, it felt as if Bishop herself was mired in citational modernism—and maybe I was able to recognize that based on my own experience working in the arts without an MFA, feeling both irritated and alienated by a lecture loaded with mostly eurocentric art references. We all get that we’re in this ghoulish cannibalistic cycle where artists are reformatting modernism — complete with saccharine nostalgia sans original progressive agenda — to the extent that they’re annihilating the past in an institutionally tasteful and collector-approved way.

While Bishop made some effort to point out works that were of this breed, she had a hard time pointing out works that offered a counter-perspective. She half-heartedly remarked during the question period that she found afrofuturism hopeful in how its looks to the future, recasting origin myths in a new way. Tellingly, she offered no names of artists creating afrofuturist works.

This bothered me, but then I wondered why I, like so many others, expect academics to know where we’re going. It’s not like two years in an MFA program or five in a PHD program so enlightens a student that they can solve all their job security issues when they graduate. And if we’ve learned anything from MFA programs, it’s that they often do little more than pump out tame, systematic art practices replete with Orwellian grant writing-honed artspeak. One could argue that affirming the current cultural moment is to the advantage of an academic like Claire Bishop.

Tanja Ritterbex, “Function Creep”, final expo De Ateliers Amsterdam (2015), Laff Box

If we’re going to fix this, it means we have to assess art-making practices that operate outside the institutionalized boundaries. Afrofuturism offers a telling counter-perspective to reformatted modernism because artists critically engage with technology and the notion of “the other” by using a speculative future as an entry point into the past. So too, does what’s being created in alternative spaces, like stand-up comedy clubs or gay bars. Toronto’s Life of a Craphead, for instance, has begun staging their popular Doored comedy-slash-performance art monthly elsewhere: in New York during a Flux Factory summer 2015 residency, or as part of an fall 2015 exhibition at Rotterdam’s Showroom MAMA that saw it become the Laff Box, a “pop-up comedy club”. Events like Hot Nuts, a popular “Queer West” drag party, has nurtured an exciting form of DIY drag performance.

These are just a few examples that take a broader view of the art making practice and are better for it. Perhaps if we follow this line of inquiry, something unexpected will happen: we’ll find out for ourselves where art is going.

Comments on this entry are closed.