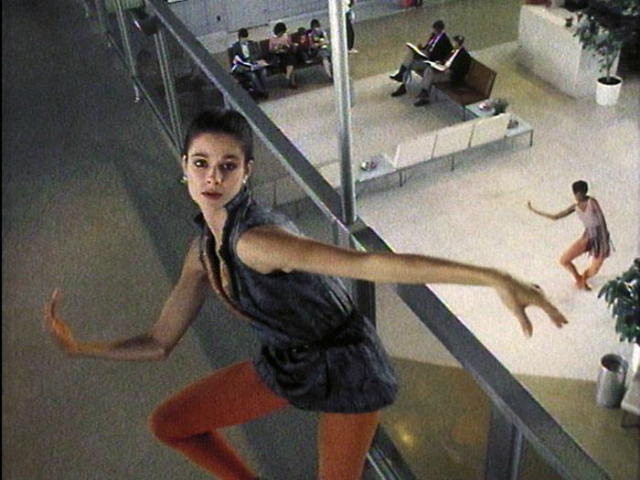

Charles Atlas’s “Ex-Romance” (1984-86). Video/dance for television. Choreography by Karole Armitage. Image courtesy of artist/Luhring Augustine

“The career of the American filmmaker Charles Atlas has been a steady but slow-burning fire for more than 40 years,” wrote Holland Cotter just last year. Despite pioneering the media-dance art form, and collaborating with dancers and performers like Michael Clark, Marina Abramović and Leigh Bowery, Atlas didn’t have his first solo until 1995 at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. That’s a big name institution to land a solo with, but it’s only been within the past decade that he’s had a steady stream of solo presentations at institutions and galleries. Those include the Tate Modern, London’s Vilma Gold, and Luhring Augustine in Chelsea.

Why the CV gap? This question naturally came up in the context of Atlas’s recent screening of his early works in Toronto. Organized by Pleasuredome, the event was a cross-section of motion movies, narratives and video featurettes accompanied by a book launch of his first monograph at Art Metropole.

“Since I worked a lot with dance, I really was considered part of another world,” he explained when I reached out to discuss the show and his work. “Now it’s super trendy to have dance in the art world, but for many years, it was considered something other. And art writers were afraid to write about it, because they didn’t want to be seen not knowing what they talked about. So I often fell in between the cracks.”

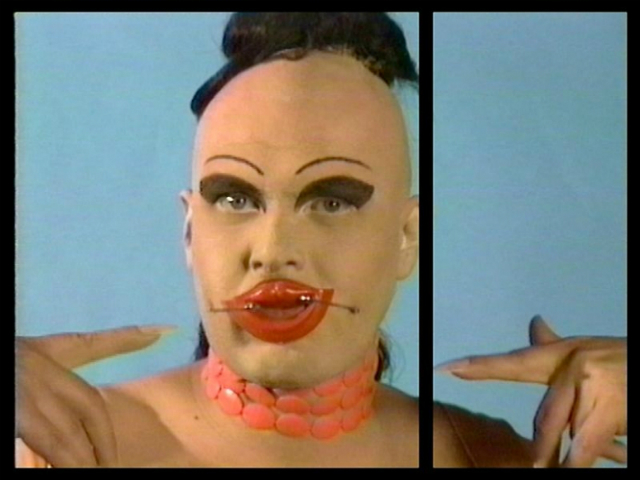

Exhibition view of Charles Atlas’s “Discount Body Parts” at De Hallen in 2012. Image courtesy of artist/Luhring Augustine

A self-taught filmmaker who made his first film in 1972, Atlas developed his media-dance form while he was the filmmaker-in-residence with the Merce Cunningham Company. When he left the Company in the 1983, he hit his niche producing what was referred to at the time as “video dance tapes” for public television. He later made documentaries, including 2002’s The Legend of Leigh Bowery, one of the first video records to take into account the legacy of Bowery’s psycho glam drag performance art and introduce his work to a larger audience. He even won a Peabody in 2008 as a director on the Art:21 series.

“I just did whatever to keep working,” he says. “I am interested in new technology, and what it can do.”

“At this point, what I do now is the sum of everything I have done before.”

It’s long been a challenge to connect the dots of Atlas’s varied career. Even now, if you don’t have a password to his catalogue on Electronic Arts Intermix, good luck: most of his early work isn’t online. When I emailed with Kevin Hegge, the filmmaker, writer and curator who co-curated the Pleasuredome programme about this period, he shared his own uphill battles in the past to view Atlas’s work. “It became frustrating because other than certain retrospectives that would pop up around Merce Cunningham, it was really impossible to see more of Charlie’s work as well.” When Hegge met Atlas at a festival screening of his Antony & The Johnsons music documentary Turning in Mexico City, Atlas confirmed that because works like Hail the New Puritan were commissioned by TV channels, he didn’t have access to the rights.

Charles Atlas’s “Hail the New Puritan” (1985-86). Video feature. Choreography by Michael Clark. Image courtesy of artist/Luhring Augustine

“I would release [Hail the New Puritan] as a film if I could, but right now, I’m not really allowed to show it,” says Atlas when I asked him. “You can’t really make money on documentaries. Someone would have to pay $200,000 for me to release it,” alluding to the rights fees for post-punk band The Fall’s soundtrack contributions.

Atlas is fine with his past being kept under the radar. “I like searching for things on the internet and not being able to find them immediately. I want people to be at least that interested in my work.”

Curators and writers like me may be less thrilled about the difficulty in accessing his early work. Atlas’s public television commissions remain exciting and innovative, especially at a time when Richard Serra and Carlota Fay Schoolman were adopting Neil Postman-like critiques about TV turning audiences into consumers. Atlas, who had also been a long time documenter of queer culture, saw opportunity in challenging normative ideas around narrative through TV’s mass viewership; stations like Channel 4 “seem to encourage the experimental approach.”

Charles Atlas’s “Teach” (1992-1996). Video installation. Image courtesy of artist/Luhring Augustine

“I always felt, even when I started out, that working with dance the way that what I did — no one would understand until a lot of other people tried it and saw what the other results were.” A self-confessed TV addict, Atlas often positioned the works as meta commentaries on the power and complicities of the broadcast medium. Ex-Romance (1987), for example, was a postmodern musical featuring choreography by Karole Armitage: fictionalized romantic entanglements danced out in settings like an airplane’s wing or a baggage conveyor belt, with Mystery Science Theatre 3000-meets-Everything Terrible! absurd commentary from two snobby public television hosts. (Fascinatingly enough, the hosts’ dialogues were written by writer Hilton Als.) “I was solving the problem of it having so many holes in the story that we didn’t get to shoot because we were being over-ambitious, so all the weird stuff came out of a non-creativity resolve,” he jokes.

Hail the New Puritan was a diaristic Hard Day’s Night riff on the notoriety and fame of then-bad boy of dance Michael Clark. The joke, of course, was Clark’s fame: he was still relatively unknown at the time, so the work was a self-mythologizing exercise, and the chance to see a dancer pogo in Leigh Bowery-designed asschaps.

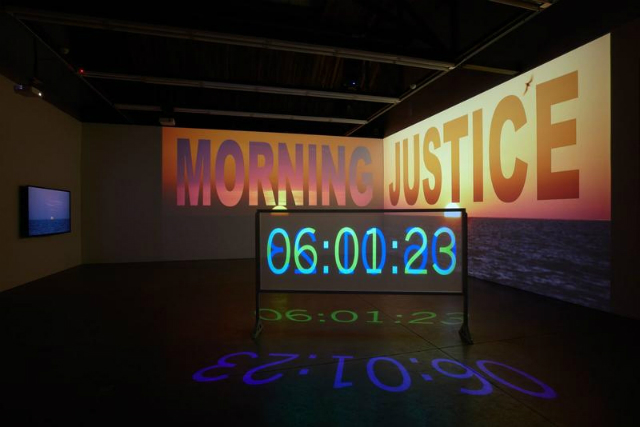

Installation view of Charles Atlas’s “The Waning of Justice” (2015) at Luhring Augustine.

Fast forwarding to his solo exhibitions, Atlas’s Waning Justice show was favorably reviewed when it was first mounted last year at Luhring Augustine. Featuring a timecoded sunset-over-water video projection alongside a politically sassy video portrait of Lady Bunny, the show went on to the Columbus College of Art and Design and will be at Toronto’s Trinity Square Video later this year. Two of his works, Teach and Ex-Romance, were acquired by the MET and MoMA, respectively. It finally seems like it is all coming together.

“Right now, I am doing another dance project, which I haven’t done in many years,” says Atlas. Made in collaboration with choreographers Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener, the project centers around a 3D film Atlas is now editing during a year-long residency at EMPAC. The film’s screening will be accompanied by live video and live performance.

After reel-to-reel editing machines and portapaks, his set-up now is often three live cameras, a hardware mixer, two laptops, and a bunch of DVDs if he wants to improvise during his live video performances. “I just roll with the punches,” he says of his relationship with the tools of his trade. “Everything’s gotten so much easier.”

“The equipment is cheaper, it’s available. When I think what I used to have to go through for video editing — oh my god, I’m scared thinking about it. It’s so different now.”

Comments on this entry are closed.