Tierra de Esperanza, installation view with “War is Over,” 1969, “Cascos/Helmets,” 2001-2016, and “Tres Montículos,” (Three Mounds) 1999-2016. The mounds are made of nearly-identical looking soil from across the Americas.

Yoko Ono: Tierra de Esperanza

Museo Memoria y Tolerancia

Plaza Juárez, Centro Histórico,Ciudad de México

On view until May 29th, 2016

Last Summer, I went to MoMA’s Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, a major retrospective that I thought was pretty terrible. The MoMA exhibition seemed so focused on didactically canonizing Ono’s eccentric practice that visitors were given precious few moments to actually engage with the work, let alone enjoy it. Conceptual art objects were neutered of their (im)practical uses and presented as precious artifacts. It felt less like a retrospective of a living artist staged by a curator, and more like an anthropologist’s attempt to explain the significance of a figure from a long-dead civilization. Mostly, the show lacked any of the fun or surprises or deadpan ambiguous absurdity that makes Yoko Ono’s work so singularly endearing.

It was refreshing, then, to see an exhibition in Mexico City that—for better or for worse—felt a little closer to a Yoko Ono happening. In Tierra de Esperanza (Land of Hope) we’re still presented with many of the same iconic excerpts from Ono’s oeuvre, but here they share the small exhibition space with hands-on pieces that change (sometimes unexpectedly) and less familiar works that still retain a sense of mystery. There’s a non-hierarchical flow to the small gallery, which positions 1960s conceptual works alongside pieces from the turn of the millennium and new Mexico-specific projects. 1964’s “Bag Piece” was presented as just the bag itself and an invitation for a pair of viewers to climb inside. Nearby, a bank of screens displays several decades worth of Yoko Ono films. Every corner of the exhibition feels activated without being cluttered. Most importantly, it’s not boring.

Watching the black and white documentation of “Cut Piece” always stirs some uncomfortable feeling of suspense, no matter how many times I’ve seen it. The 1965 performance comprises Ono looking awkwardly vulnerable on a stage while audience members snip away her clothing with scissors. In the beginning, different participants look alternately bashful and mischievous, though as time progresses, the cutting gestures become increasingly violent and the tone becomes much more sinister. It’s widely considered a performance art classic. But in this exhibition, it manages to feel surprisingly timely—here it’s contextualized with newer works that explore themes of consent, the artist-viewer relationship, and violence against women.

In “Resurgiendo,” an ongoing piece from 2013, Ono invites women to submit photographs of their eyes alongside personal stories of gender-based discrimination or abuse. These accumulate into a towering formal grid of informal-feeling 8.5×11 printer pages. The narrow bands of eyes at times read like a face glimpsed through a burqa or Zapatista-esque balaclava. It’s an unsettling viewing experience, because up close one is compelled to engage with each individual story. At a distance, the sheer volume of eyes and their blocks of text become overwhelming—one could not possibly read each of these tragedies. It’s a powerful installation for Mexico, where outside the capital, the drug wars and poverty have created a climate of violence with rape and murder rates so high they’re frequently described as an epidemic.

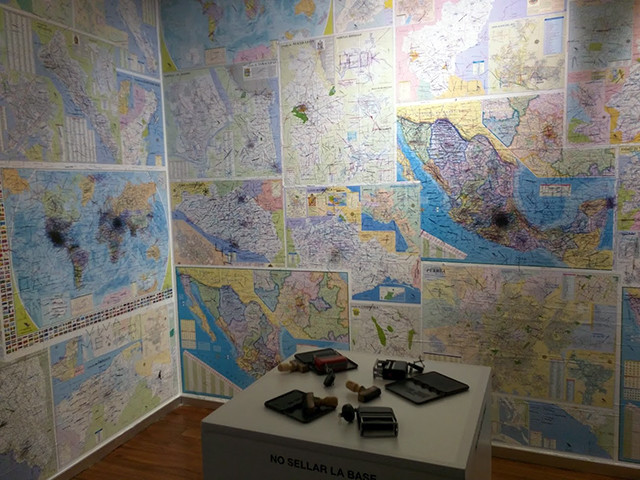

“Imagina la Paz. Pieza de Mapas” (Imagine Peace. Piece of Maps) 2003 – 2016, installation view.

While Resurgiendo bucks the exhibition’s titular optimism, most of the other works in Tierra de Esperanza reflect it. In “Imagina la Paz. Pieza de Mapas” (2003-2016), one corner of the gallery is wallpapered with maps, from global to local. Visitors are invited to blot out the arbitrary names and delineations of political entities with rubber stamps that read “IMAGINA LA PAZ” (imagine peace). Yes, it sounds extremely cheesy. But I surprisingly didn’t hate it. That might boil down to optics—the crowdsourced stamps tended to congregate in satisfying constellations, blurring the US/Mexican border or replacing those fist-shakingly-ill-conceived political boundaries of the Middle East with a black hole.

Mostly, though, it’s nice to see Ono’s work as something dynamic and interactive (as she intended) and not a static relic of more free-spirited times. Nothing here felt too precious, a quality best exemplified by “Pieza de Reparación,” where viewers were invited to reassemble broken pieces of colorful pottery with tacky glue, a pedestrian take on the Japanese kintsugi tradition of using gold to mend cracks in porcelain. It’s hard to visit this show without thinking how much more enjoyable Yoko Ono’s work is when it’s actually, tangibly accessible rather than being spoon-fed as an art history lesson.

At MoMA, it felt as though the institution was compelling us to take Yoko Ono very, gravely seriously. At the Museo Memoria y Tolerancia, the suggestion seemed to be to enjoy the unironic absurdity of playful (but politically-informed) gestures. It’s a light-handed curatorial tone that’s appropriate—after all, the rest of the museum is devoted to pretty grim reflections on violence. Yoko Ono is at her best when she’s allowed to plainly—if not either too obviously or cryptically—speak for herself. Indeed, “Teléfono en Asombro” (a re-staging of the 1971 “Telephone in Amaze”) consists simply of a transparent plexiglass maze with a telephone in the middle. It’s surprisingly harder to navigate than it looks. At the center, there’s a phone, along with a note that says Yoko Ono will call whenever she’s ready to talk. It’s direct and inscrutable at the same time—exactly why Ono’s loveable.

“Gente Invisible” (Invisible People) 2011-2016. This is a pitch-black room to the side of the gallery full of cartoon-like plastic figures. When a visitor is about to bump into one, a strobe is set off. I didn’t realize until reviewing this GIF that the flashing image is the ruins of Hiroshima.

Comments on this entry are closed.