From left: Whippersnapper’s programming director Josh Vettivelu, Deanna Bowen and Abbas Akhavan. Credit: Whippersnapper Gallery

On a sunny Sunday afternoon, the second floor of Toronto’s Theater Center was packed with artists for the panel DAMNED IF YOU DO: A Conversation on the Politics of Refusal. Co-presented by local artist-run center Whippersnapper Gallery, the panel focused on stories and strategies from the trenches of the “marginalized”: namely, the tricky pursuit of navigating art and funding systems as an “artist of colour” or “visible minority” or whatever fraught PC term can describe what it means to be a racialized body in the art world.

Led by artists Deanna Bowen and Abbas Akhavan, the talk was intentionally geared towards emerging artists, and addressed the varying level of anxieties one encounters when choosing to take advantage of cultural equity policies. Whether it’s the choice to apply for a culturally diverse grant, or even contending with a Black History Month group show invite, the talk surveyed the strings that come attached to tacitly accepting the advantages of “inclusion” and “access”: specifically, the expectations to “perform” a subscribed notion of identity politic.

“Get that money when you can get that money,” said Bowen bluntly during the course of the talk. Awareness, discussion and negotiation, we were told, is the clearest path to resistance. But cases in which artists refuse the money are rare, so what constitutes rejection seemed less clear. What happens to those who don’t take the money? Especially in a city like Toronto, where artist-run center culture is so dominant that one of the primary anxieties for artists is contending with the influence of institutional bureaucracy on their work. As my friend, the writer and academic Joseph Henry suggested, it’s akin to New York’s “market” and artists’ concern about making work that conforms to the prerogatives of the market.

Bowen and Akhavan were appropriate panelists to lead this conversation, especially given that the Toronto artists were recently validated by the same American institution. Bowen, a mid-career video installation and performance artist, is a 2016 Guggenheim fellow. The Tehran-born Akhavan was included in the Guggenheim’s current But a Storm Is Blowing From Paradise: Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa group show; its April 29 opening was overshadowed by the Guggenheim’s decision to break off talks with the Gulf Labor Coalition (GLC) regarding worker rights for the migrant labourers hired to build its Abu Dhabi outpost.

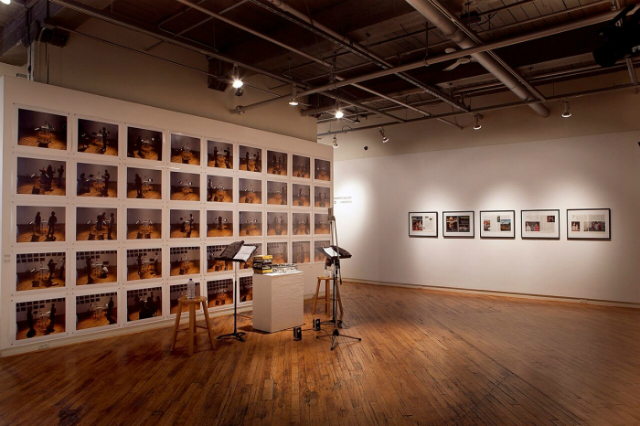

Installation view of Abbas Akhavan’s “Study for a Monument”, Mercer Union, 2015. The sculptural installation was recently acquired by the Guggenheim. Credit: Mercer Union

Akhavan was one of the show’s ten artists who signed and released a letter expressing disappointment with the Guggenheim’s abrupt decision. At the talk, he was candid about being an artist supportive of the GLC’s efforts, and only accepted being part of the show when he learned that the GLC’s obligation wasn’t to boycott all Guggenheims — just the Abu Dhabi location. He discussed how he had sold his work, Study for a Monument, to Guggenheim New York under the premise that it would never enter the collection or be lent to Abu Dhabi. At the time of the deal, he felt resolved with exercising his agency as an artist. Yet he felt blindsided when ten days before the show, Guggenheim Museum and Foundation Director Richard Armstrong had broken off talks with the GLC.

“It was just interesting to see the way at a moment of agency, you become a pawn to a moment that you have no control over,” he says. “So there was this great ambivalence in suddenly being complicit by being in a show that you felt you had protected yourself against its contradictions over labor law issues, and at the same time, ten days before the opening, basically all the artists [became] somehow complicit with that space, and also its politics.”

For Bowen, who grapples in her work with the collective histories of slavery, migration and racism, the Guggenheim fellowship gave her pause, especially since it coincided both with the Abu Dhabi controversy and the announcement of their new social practice art initiative. (She deemed the latter “a curiously-timed phenomenon.”) She was candid about why she accepted the fellowship cheque: “as a black queer feminist, when you get a really big cheque from an American institution” — drawing attention to the current value of the Canadian dollar — ”I didn’t turn it down, but I had to ask, ‘how far do I take my political concerns?’” Bowen came to the conclusion that “this year I’m taking the money, but I take it with a pause.”

Installation view of Deanna Bowen’s “Paul Good/Robert Sheldon Character Study,” 2012. Credit: John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation

From there, Bowen highlighted the pressures she has faced from American institutions who seems to think the “black art tendencies” of Canadian artists are the same as American. The irony, however, was that even Canadian institutions themselves “want you to create like you’re from somewhere else,’ she said ruefully. Bowen, for instance, has created work about her own African American ancestors who migrated north in the early 1900s and helped found one of the earliest black immigrant settlements in Northern Alberta. But as a third generation Canadian, she feels Canadian institutions are more comfortable perpetuating a historical narrative that may not include her own lineage. It’s easier to continue telling the same “new Canadians” story.

Akhavan discussed frankly the challenges he faces as an Iranian artist contending with a subscribed way of being an artist from that region. “I don’t have a topical conversation with a carpet,” he said, citing the Persian cultural object as an example of the trendiness he sees right now among artists toward manipulating “Middle Eastern instruments”. He expressed his frustration, however, with how an artist like Chris Burden could use such a common trope without ever being called out for it, just as Picasso had when he worked with African masks. He also commented on the pressure artists from marginalized communities face in having to “destroy [your lineage] in order to exist outside the shadow” of older generations. In other words, in order to carve out a niche for your own voice, you are expected to be different. This inevitably creates an antagonistic relationship that’s not always beneficial to either generation.

The conversation was an honest dialogue about the exhaustion that comes from being positioned as the “exceptional”: the “curatorial challenge,” according to Bowen, of being both “a unicorn” and then “a unicorn that no one knows what to do with.” Akhavan framed tokenism in terms of “hospitality”, and “how artists are placed within certain institutions to make them look good,” essentially becoming a predetermined placeholder to meet their POC quota.

Absent from the conversation, however, was the business of being a marginalized artist outside institutional frameworks, like pursuing an additional livelihood that’s not reliant on grant support. Given that the talk was organized by an artist-run center and focused on artists themselves navigating art and funding systems, I was surprised there wasn’t much talk about an artist-run center’s own place within these systems. So much of local artists’ livelihood, not to mention artist-run centers themselves, are dependant on government funding. It operates at such a scale in the city that if an artist-run center doesn’t get, say, a key chunk of their operational funding from the Ontario Arts Council, along with a Canada Council for the Arts project grant to support an exhibition in their programming, their reduced capacity has a huge impact on the health of the local arts community.

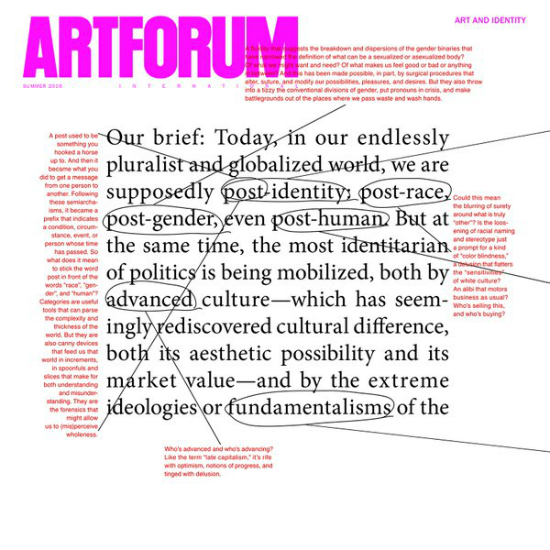

The Barbara Kruger cover of Artforum’s “Art and Identity” summer issue. Credit: Artforum

Further, as an artist of color, entrance into certain artist-run centers — especially those that came out of the cultural equity politics of the 1990s — are spaces that have their own hierarchies to contend with. Artist-run centers that survive on government funding must demonstrate they meet the set requirements. That requires it’s own song and dance, which trickles down to the artists they serve.

But the most unintentionally frustrating aspect of the conversation, which came up during the the Q&A period, was the acknowledgement that there was a lack of “inter-generational” dialogues within communities themselves. “People who are a decade older than I have done the same labor that I’m doing,” said Whippersnapper’s director of programming, Josh Vettivelu. Artforum’s summer issue is all about “Art and Identity”, and features a cover with “post-identity” text marked up with red edits by Barbara Kruger. If 1990s identity politics are so hot right now, why have we avoided introspection on how it has shaped and continues to shape our own local histories?

The frustration isn’t new, but in the context of this conversation, I thought Vettivelu’s observation deserve further parsing. After all, it was the work of local elders — I think in particular of figures like dub poet Lillian Allen and video artist Richard Fung — that contributed to the shaping of cultural equity policies to begin with. Occupy Wall Street founder Micah White has talked about how social movements require a long-term perspective. It’s taken us forty-plus years to see how artist-run center culture has shaped Toronto art-making. It’ll likely be another twenty years before we truly see how these activist-informed policies fully re-address systematic discrimination.

For a talk that was about the politics of refusal, and contending with the anxieties that come with the decision to check off boxes that mark you as a “visible” minority, the panel basically came to the conclusion that it’s OK to acknowledge your discomfort. As long as artists don’t let the artist-run system and granting landscape determine their art, taking the money that comes from this field should ultimately help, not hurt their practice.

Comments on this entry are closed.