Hermonie “Only” Williams, “Suttee,” charred wood.

Hermonie “Only” Williams: Not Now

Gallery Four

405 West Franklin Street, 4th floor

Baltimore, MD

On view until July 22nd, 2016

One of the first pieces a viewer encounters in Not Now is “Suttee,” two spiraling bundles of charred, sharpened dowels on side-by-side plinths. The title refers to the archaic Hindu tradition of a widow committing suicide by jumping into her husband’s funeral pyre. As in much of Hermonie “Only” Williams’ work, the notion of symmetry is problematized.

There’s a brutality to these meticulously-considered, simple shapes. The piece is “dark” on multiple levels—from certain angles, the charcoal crust absorbs so much light it feels like an optical illusion—a jagged black hole of velvet cut into the white cube. But from other perspectives, the remarkably uniform carbon surfaces catch the light, revealing subtle flaws in sudden relief. It’s an extraordinary quality of a ubiquitous, albeit loaded, element—carbon is the building block of life, and humanity’s re-shuffling of it from one form to another will likely be what causes our extinction—ashes to ashes. But this odd lustre might only be fully appreciated and exploited to such affect by someone who spends a lot of time staring at charcoal and graphite, someone who obsessively seeks out imperfections or idiosyncrasies in otherwise perfect geometries. Looking at the rest of the work in Not Now, one gets the impression that Hermonie does a lot of the above.

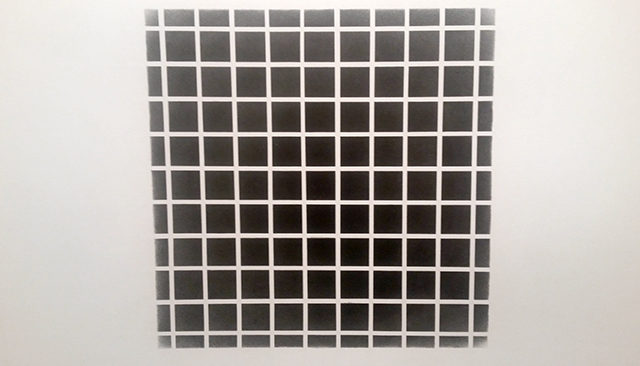

One half of “Omnipresence,” graphite on paper.

In “Omnipresence,” a diptych comprising one black-on-white and one white-on-black grid, there’s a faint, almost mechanically-rendered gradient in the “black” graphite. It took me a moment to realize the impossibly-precise grid was defined by shades of gray, darkest at the center and almost imperceptibly lighter towards the edges. It’s a feat of seemingly superhuman mastery over the clumsy art of drawing. The effect is akin to a medium format photograph of a fabricated minimalist artwork, fed through some Instagram filter to add a softening vignette. Ironically, cell phone photography does no justice to the work.

There’s a similar element of improbable perfection in another, untitled graphite work on paper (below). The step-and-repeat pattern of shaded rectangular prisms recalls assembly-line printing techniques, though minute discrepancies between each gradient reveal that the work was in fact hand drawn.

“Untitled,” graphite on paper.

But perhaps the “screen saver” is a more fitting point of technological comparison for the composition of cascading boxes—in a sense, this piece is all about passing time. Idle hands, much like a static image on a monitor, are generally prescribed against. And therein lies the vulnerability in Hermonie’s seemingly sterile practice. According to the artist, “These artworks are an investigation into the ethical and aesthetic problems at the core of ‘personal expression’.” Her artist statement speaks of depression and anxiety, and we get the impression those ailments can be escaped by becoming a machine of sorts. How much easier would it be to exist as a CNC plotter—fulfilling a command to endlessly, mechanically render cold forms—than to emotively inhabit the archetype of tortured artist?

If the millennial zeitgeist is to play out our personal-as-political dramas using new media—from cyberfeminist subversions of social media to ironic hijacking of surveillance strategies, oversharing-digital avatars, or 3D-printed self portraiture—Hermonie’s work exists as an anachronism that looks both to the art-historical past and a dystopic future. Her practice is Not Now indeed. Rather than insert her ghost into the machine, she performs as machine; an escapist cyborg. These drawing instruments are the prosthesis of a mind that aspires to be more like a computer, somewhat ironically using the classical materials of Studio Art 101 (charcoal, graphite on paper) to approach the detached vocabulary of late modernist minimalism. In her words: “Graphite, inherently dark and reflective, recedes from the viewer with an introspection so severe that it appears to cave in on itself. Drawings that seem so heavily obvious as to make ascribing further significance uncomfortable.”

“We’ve All Been There,” polished enamel and MDF.

And yet the aesthetics of the fabricated object do carry their own emotional associations. Chiefly: desire. One of the most successful 3D works in Not Now is a flawlessly sanded, black-enameled, and polished slab of MDF in the shape of a rigid pillow. Called “We’ve All Been There,” it resembles a laptop, or perhaps an oversized version of an early-model iPhone as it would’ve looked fresh from the assembly-line. It’s sexy. It looks expensive.

This is the strange tension at the heart of Hermonie “Only” Williams’ practice: the aesthetics of mass-production elicit a desire to consume and possess. Yet the knowledge that an object or image is handmade compels us to seek out our own empathic response as viewers. When the two align, we’re left in a state of wonder in front of something doubly precious. Sometimes trying to produce something devoid of an emotional reading can result in work that’s loaded and moving beyond expectations.

“Be That as it May,” inkjet print, polished enamel, MDF. The print is, to the best of my knowledge, the only work without evidence of Hermonie’s hand.

“Some More than Others,” charcoal pigmented cement. Slightly-off symmetry is a recurring theme in Hermonie’s work.

From left to right: “After and Before,” “Then When,” and “Not Now,” polycarbonate, installation view.

From left to right: “After and Before,” and “Not Now,” (edition of two, both here) polycarbonate, installation view.

“Well,” charcoal pigmented cement.

“Might as Well Get Used to It,” charcoal pigmented cement.

Comments on this entry are closed.