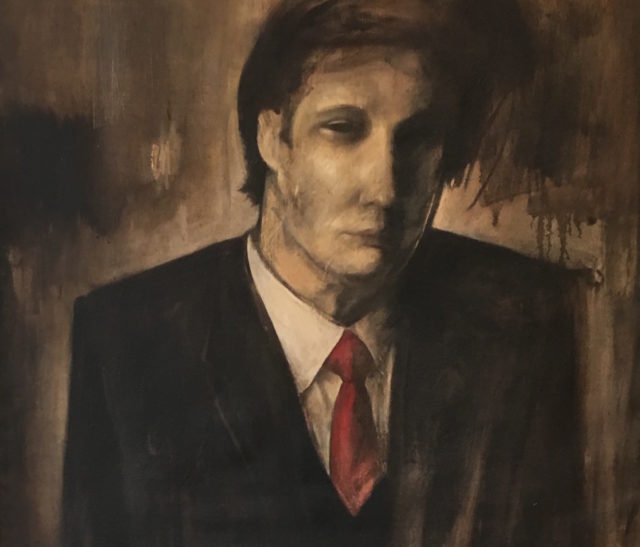

Detail of Andrew Castrucci’s Untitled (Donald Trump) (all photos by author for Art F City)

Martha Rosler: If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ve!!

Mitchell-Innes & Nash

534 West 26th Street, New York, NY

On view until July 9, 2016

One of the first works you see in Martha Rosler’s exhibition If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ve!! is a dark and ominous portrait of Donald Trump. Leaning against a wall, the Trump tableau sits behind three glass bottles filled with urine. Is the piece a biting comment on Trump’s pissant Republican presidential campaign? Is it a playful but terrifying foreshadowing of his future official White House portrait?

Andrew Castrucci’s Untitled (Donald Trump) is neither. A quick glance at a nearby wall label confirms Castrucci’s Trump was painted in 1986. Created well before Trump’s presidential ambitions, Castrucci’s work instead critiques Trump as a reckless developer gobbling up large swaths of New York and Atlantic City real estate. As relevant then as it is now, Untitled (Donald Trump) reveals the uncanny confusion between the past and present that runs rampant throughout Rosler’s overstuffed exhibition at Mitchell-Innes & Nash.

Titled after a dismissive quote by former New York City Mayor Ed Koch, If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ve!! is a revival and expansion of Rosler’s 1989 three-part exhibition If You Lived Here…. The original exhibition at Dia Art Foundation’s former Wooster Street space brought together artists, squatters rights groups, an organization of homeless people called Homeward Bound and numerous additional activists. These participants addressed homelessness, housing inequities and other issues facing tenants in overcrowded cities such as–but not restricted to–New York. In addition to the three shows, If You Lived Here… also presented four community forums to bring the visual dialogue forged in the exhibition to the public.

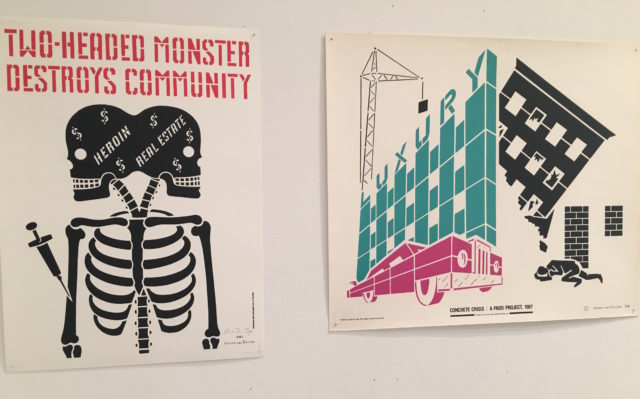

Anton Van Dalen, Two-Headed Monster, 1983 and Concrete Crisis, 1986

Nearly 30 years later, Rosler returns to If You Lived Here… with the help of a mysterious autonomous group, The Temporary Office of Urban Disturbances, which takes over Mitchell-Innes & Nash after their formation in May 2016. This is not the first time If You Lived Here has been revisited in an exhibition format. In 2009, e-flux launched an archival project If You Lived Here Still featuring boxes of photographs, documents and other assorted ephemera related to the organization of Rosler’s storied 1989 exhibition. While the same materials appear in If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ve!!, the new show perhaps too ambitiously extends e-flux’s precise archival focus to include today’s artists and activists.

Grappling with a multitude of disparate voices, the layout of the exhibition is unsurprisingly overwhelming. The exhibition–like its original–is separated into three sections: Home Front (on gentrification and tenants’ rights), Homelessness: The Street and Other Venues and City: Visions and Revisions. With the first two parts recently shown at the New Foundation Seattle, the Mitchell-Innes & Nash installment represents a combination of all three segments including an expanded version of City: Visions and Revisions, according to the press release.

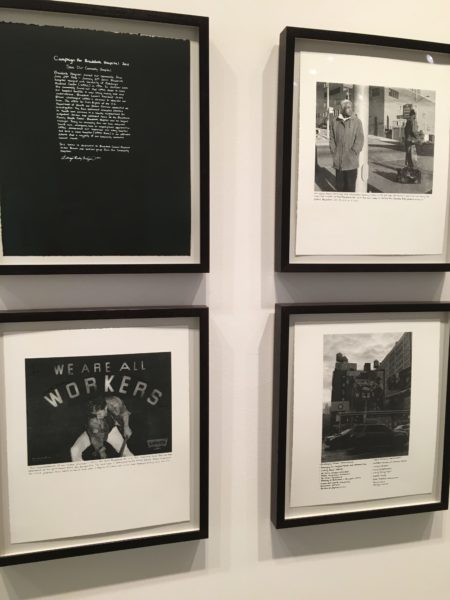

Installation view of “If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ve!!” at Mitchell-Innes & Nash

Even though the press release explains these themes quite plainly, that clarity is lost in the exhibition itself. The gallery is covered from floor to ceiling with art, activist posters, banners, flyers, videos, enlarged newspaper articles and tables of tightly arranged and overlapping ephemera. Quotes including the iconic protest slogan “Under the cobblestones, the beach” are emblazoned on the walls in a colorful shock of spraypaint. Even the gallery’s structural columns are plastered in flyers, rendering the exhibition an ADD-sufferer’s worst nightmare.

The exhibition’s chock-full aesthetic is, on some level, understandable–a retro throwback to the artist-organized, politically motivated exhibitions of the 1980s and 1990s by art collectives such as Collaborative Projects (Colab) or Group Material. However, even though I went to the gallery three times, I found it challenging to fully digest the exhibition. I felt inundated by the endless possibilities of reading materials.

Mel Rosenthal, The South Bronx of America, 1970s

A potentially inadvertent effect of this overhung exhibition is that the divisions between the art included in the original exhibition and more contemporary work become indistinguishable. Like Andrew Castrucci’s Untitled (Donald Trump), this slippage between the past and the present can be seen in Mel Rosenthal’s post-apocalyptic photographs of the economically devastated South Bronx in the 1970s. Rosenthal’s photographs are irrevocably tied to a distinctive place and time when the Bronx was still burning. And yet, without captions, these images of urban decay could also be reflections of today’s struggling cities like Detroit.

This interchangeability of real estate concerns seems to indicate that issues of homelessness, tenants’ rights, greedy property owners and gentrification may never end. But, as the exhibition depicts, neither will artists and activists’ passionate attempts to fight back. The collectives and individuals artists continually pinpoint pressing problems in their own communities and demand change whether through art or direct action.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, From the Braddock Hospital Photo Campaign, 2011

Nowhere is this more apparent than in artist LaToya Ruby Frazier’s 2011 photographic series Braddock Hospital Photo Campaign, which narrates the closure of the local hospital in her struggling hometown Braddock, Pennsylvania. In a handwritten introduction, Frazier describes the shuttering of Braddock Hospital as not only a traumatic loss of adequate healthcare, but also the loss of the region’s biggest employer. With many Braddock residents suffering from chronic illnesses due to their proximity to the steel plants (including Frazier herself who lives with lupus), Braddock Hospital became a de facto community that disappeared when the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) built a new hospital in a more affluent suburb.

In her series, Frazier places photographs of Braddock residents protesting the closure of Braddock Hospital with the romanticized vision of Braddock in Levi’s “Ready To Work” campaign. Capturing Levi’s billboards in Manhattan, Frazier presents a damning juxtaposition between ads of Braddock as a rugged working town at the same time the city’s biggest employer shuts down.

As she forges an emotional connection between the often forgotten poor residents of Braddock and the typical upwardly mobile Chelsea gallery-goer, Frazier demonstrates the strength of If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ve!! Despite its overpowering installation, the exhibition lays out the ideas of artists and grassroots activists in a commercial gallery setting that is normally designed to motivate sales rather than political change. Refusing to isolate art from politics, If you can’t afford to live here, mo-o-ve!! just might inspire some unsuspecting viewers to mobilize.

Comments on this entry are closed.