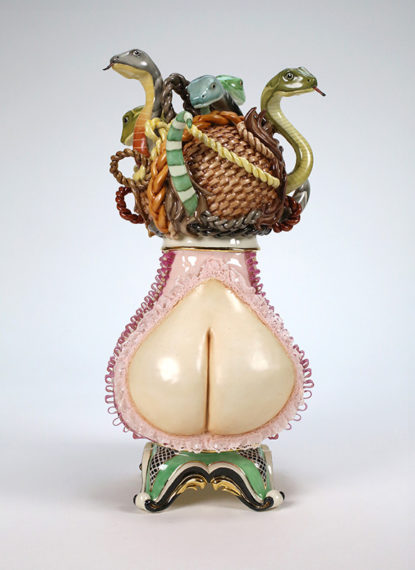

Jessica Stoller, Untitled (slip), 2016, porcelain, glaze, china paint, lustre (Courtesy of the artist and P•P•O•W, New York)

Dainty and delicate, porcelain is not the typical medium for radical feminist art. However, Brooklyn-based artist Jessica Stoller’s porcelain sculptures seem closer to Karen Finley’s chocolate sauce-drenched performances than precious Royal Doulton figurines.

Depicting oozing glaze, dripping sickeningly sweet confections, rippling flesh and cavorting nudes, Stoller’s sculptures shatter the normally quaint porcelain subject matter. She subverts long held standards of female beauty, consumption and femininity by using this historically charged medium to portray the grotesque.

It becomes immediately clear when talking to Stoller that she remains enthralled by the history of porcelain. “Porcelain means pig vagina–look it up!” she exclaims. With one statement, Stoller shows her transgressive hand. Buried under all the historical and academic interest in the material lies an in-your-face confrontation of the subjugation of women in society.

Fittingly, a selection of Stoller’s porcelains are currently on view in PPOW Gallery’s summer group show The Woman Destroyed. Curated by Anneliis Beadnell, the exhibition takes inspiration from its namesake–Simone de Beauvoir’s 1967 feminist text. De Beauvoir in The Woman Destroyed critiques the treatment of women as seen through the eyes of three middle-aged characters. While the exhibition features a refreshingly diverse lineup of artists, Stoller’s sculptures stand out due to their anachronistic medium and alluringly abject content.

I spoke with Stoller over email on her motivation to work with porcelain, the importance of sweets in her sculptures and how she sees her art engaging with feminism.

How did you first begin working with porcelain and what inspires you about the material?

I started working with porcelain several years ago and became really fascinated with the European history of creating a material that rivaled that of Asia. In a nutshell, the resulting story involves an audacious alchemist, visionary artists and a porcelain-crazed king. Janet Gleeson wrote a great book on the subject entitled The Arcanum that reads like fiction yet is historically based.

I am interested in clay, specifically porcelain, for a myriad of reasons. The history of the material is so vast (spanning cultures/centuries) and from a technical standpoint, there is always more to learn and new ways to experiment. The material is also full of contradictions. It was once emblematic of distinct imperialist taste and later dismissed for being decorative, hence “feminine.” The physicality of the clay and the transformative process is really satisfying–not to mention clay is the master mimicker and can be modeled to resemble a thigh speckled with cellulite, a rotten apple or a strand of pearls. I am drawn to this tumult of history and interpretation; it serves as endless fodder for the work.

Jessica Stoller, Untitled (weave), 2015, porcelain, glaze, china paint, lustre (Courtesy of the artist and P•P•O•W, New York)

Filled with flesh, sumptuous garments and dripping desserts, your sculptures tread the line between the saccharine and the sickening. What is the role of abjection in your art?

It serves to disrupt the narrow parameters of a kind of static, idealized femininity. Most women can relate to a body without fixed borders–one that leaks, swells and oozes. I think these natural impulses tap into a large continuum of life and death. I am interested in ideas of excess and restraint and how those visuals become potent metaphors to challenge expectations and tropes.

I’m particularly interested in the use of food in pieces like Untitled (Spoil). There is a long history of women employing food in subversive feminist art such as Carolee Schneemann’s Meat Joy. What interests you about portraying this overabundance of sweets and do you see your work as engaging with the history of food in art?

Right. I think the use of food in my work ties into many traditions from vanitas painting, feminist art and the broad use of clay as a functional vessel. Back to your question regarding sweets, sugar was once highly valuable and was modeled into allegorical figures and elaborate scenes that adorned grand dining displays of 18th century courts. As sugar became more available–as a result of colonialism, I assume, porcelain became the new desired material that signified wealth and taste and was displayed in similar ways. Therefore, the overabundance of sweets takes on many complicated meanings that tie into patriarchy, imperialism and ultimately, the subversion of said markers through the work.

I am also interested in the ideas of the “feminization” of sugar and how once ubiquitous, it was no longer tied to wealth and male power. It became “feminized.” Later in the 19th century, it was sold and marketed to women as being innately connected to their gender with the implied subtext of being frivolous and lacking value.

Several of your new porcelains are on view in PPOW Gallery’s current group show The Woman Destroyed. How does your art address contemporary women’s issues?

I do see the work engaging with contemporary women’s issues and the tone of that dialogue changes with different works. My methods vary–from the explicit to the subtle, from humor to grief. To be honest, I think of my work as a kind of refuge from the often depressing treatment of women and girls in the world. My sculptures serve as a vehicle for me to dismantle, reimagine and revisit historic and contemporary issues, myths and the current culture.

Jessica Stoller, Untitled (gather), 2016, porcelain, glaze, china paint (Courtesy of the artist and P•P•O•W, New York)

Your sculpture Untitled (Gather) reminds me of the last scene in the film The Witch with its nude–or almost nude–women in a dense forest. It has this supernatural and fairytale quality. While clearly art history is an essential influence for you, do you draw inspiration from other cultural sources? What are they?

Untitled (Gather) was inspired by a few ideas, in particular an image of an 18th century engraving by Charles Eisen, which depicted “the devil defeated by vaginal display.” I loved this idea/phrase/image, and it sent me to research its history. As a result, I learned about ana-suromai–a Greek word essentially meaning “to raise one’s clothes.” I came to find this phenomenon stems back to the ancient Egyptians, as recorded by the Greeks, and spans continents and cultures. A practice that could scare away advancing armies or increase harvests and fertility. I learned much of this history in Catherine Blackledge’s The Story of V.

Another point of cultural influence was hysteria and my research led me to the Greeks essentially thinking the female womb “wandered,” hence making them sick by their very design. Ultimately, this thinking would be the basis for the 19th century invention of hysteria–a fascinating but deeply troubling “female affliction.” I also liked the art historical motif of the three graces, hence three women not one. I liked the idea of–instead of being seen as hysterical–the women were getting back in touch with a deep-seated power.

In general, I am always looking and taking in the world around me for inspiration: fashion, current events, art history, popular culture, my body, etc.

Beyond their content, the physical presence of your sculptures fascinates me. At the opening of The Woman Destroyed, I was terrified I would knock down one of your sculptures. I remember feeling the same way at your 2014 solo show Spoil. What do you think the physicality of the porcelain adds to the sculptures?

Paradoxically, ceramic material is incredibly strong. In my work, however, I do have many filigree-like components that tend to make the work really fragile. I have wrestled with ideas about display. Do I put it on a vitrine or not? I think that without the vitrine, viewers are even more careful when viewing the work. That implied fragility is right in their face and adds an extra layer. The mash-up of textures, forms, pattern and color gives the work a truly tactile sense that is really seductive. I am a maximalist at heart and clay allows me to really investigate the physicality of the material in both content and form. I also like the duality of the work looking very fragile yet the content of the sculpture is very powerful and provocative.

Comments on this entry are closed.