Is there a secret, intertwined history that ties together mass media, spiritualist con artists, pulp fiction and the unreliability of the image? Tony Oursler’s “Imponderable” would like you to think so. The multimedia artist’s latest work (on at MoMA through January 8th, 2017) is a 90-minute immersive video experience that attempts to draw connections between all of those topics as well as his own familial autobiography and other threads that relate to his collection of spiritualist memorabilia. Unfortunately, when the work seems to come close to solidifying a thematic relationship between its various subjects, it tends to feel a bit like a magician who has all the elements for his act, but never manages to execute a successful trick.

Through a series of vignettes, the artist tells the story of his real grandfather, Fulton Oursler, who was a multi-talented man working in stage magic. In partnership with Harry Houdini, Fulton made it his personal crusade to debunk the various spiritualist mediums and psychics that were popular during the 1920’s and 30’s. This was a time when illusionists functioned as men of science and trick photography techniques were easily mistaken as undeniable proof of ghosts walking among us.

This premise serves as a jumping-off point to explore Oursler’s (the artist) collection of ephemera from the time period, as well as connect the practices of old-school illusionists with modern mass media spectacle.

In addition to being a renaissance man who palled around with Houdini, Oursler’s grandfather was married to a writer of pulp novels and screenplays named Grace Perkins. She was a prolific author and a troubled drug abuser. Over the course of the video, Oursler rotates between vignettes that focus on the magicians debunking pseudoscience and Perkins feverishly writing and being committed to the looney bin. Perkins purpose in the narrative seems to represent the next stage of what entertainment would become and her mental breakdown doesn’t bode well for society.

Even though this premise is handled in a disjointed manner with all sorts of stylized visual effects, there’s a more straightforward narrative here than normally found in video art and Oursler is not particularly skilled at handling it. A title card will appear that’s written in that cheeky novelistic style that tells you what’s about to happen in this chapter and then that thing happens. There’s little wit to be found on these cards so they tend to spoil you rather than tease you. The scenes then play out with trippy multilayered imagery, unnatural dialogue and flat avant-garde acting.

On top of the title cards and “then this happened”-style of pacing, the gallery that one has to cross before entering the theater is populated with items from Oursler’s personal collection of spirit photographs, Houdini correspondence, Pulp movie posters, magician’s handcuffs and other similar objects. I love this kind of stuff and devoured everything in the room, which turned out to be a mistake. The items and their accompanying labels outline the basic story of the video and once you know it, the early parts of the main feature can get really tiresome. In the hands of a solid storyteller this would be a trivial matter, but Oursler’s strengths lay in deconstruction and visual experimentation.

As the story plays out, historical information is simply delivered while some lovely patterns and visual overlays spice up the aesthetics. Other times there are sequences that grasp towards the poetry that Oursler seems to want to convey. When Kim Gordon whips out a tambourine in an abrupt musical interlude, we’re thrust into a tour-de-force of noise and imagery. The whole video could have used more of this sort of unhinged, just-going-for-it attitude.

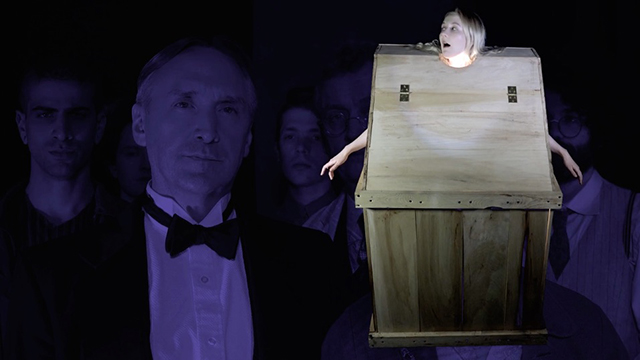

Another successful scene involves a psychic who is locked in a box by Houdini so that she can’t use any tricks to ring a bell with her mind. The sequence has a serious claustrophobia that’s heightened by physical pounding under the floorboards of the theater.

That pounding is part of what’s being dubbed a “5-D” experience. A lighting rig provides sensory effects and the screen itself has a few layers that produce an illusion of depth without requiring special glasses. This screen configuration adapts an old magician’s technique called Pepper’s Ghost. The meeting of conceptual form and content here matches up perfectly. It’s a delight to have little balls of light float off the screen and around the room, smell-o-vision scents waft across your nose and chilly winds blow in a snowy scene.

The one sequence that’s almost flawless, on a visceral level, actually illustrates the problem with the overall work, though. Harry Houdini is whisked over Niagara Falls while having a philosophical conversation with Fulton Oursler who yells from the shore. It’s all decidedly unrealistic and loopy. And as an experience, it brought me in, while the dialogue pushed me away. Fulton warns Harry of the encroaching ubiquity of the cinema. He pontificates on the dangerous architecture of the movie theater versus the live stage. It’s a sub-Godardian notion about how the audience knows the room is split in a live circumstance and they’re aware that deception lies behind the curtain, but the silver screen gives an illusion that will be harder for the public to navigate.

This is the only time in “Imponderable” where I thought the ideas were starting to come together. Theater design, visual illusions, illusions in the form of belief, allusions to an actual stunt by Houdini, the movies that will eventually supplant these entertainers in popular culture and the moralities at play in the work of an entertainer are all being touched upon. But when I start to dig into it, the implications seem just out of reach. A melancholy mood hangs over the piece, that is largely fueled by J.G. Thirlwell’s excellent score, but I’m not sure of what it mourns. Maybe a moment when popular entertainment became something more sinister? Maybe.

It’s easy to forgive an experiment for not proving its thesis; it’s harder to forgive a work that manages to be boring while it stimulates the viewer on every sensory level. The postmodern distancing devices (phony acting, multiple screens, gimmicky theater etc.) in the work seem to intend to make you aware of the manipulations going on in media. An echo of the manipulation employed by the con artists of the parlor. They work very well at pushing us out of the work. So well, that we disengage and there’s limited room for beauty.

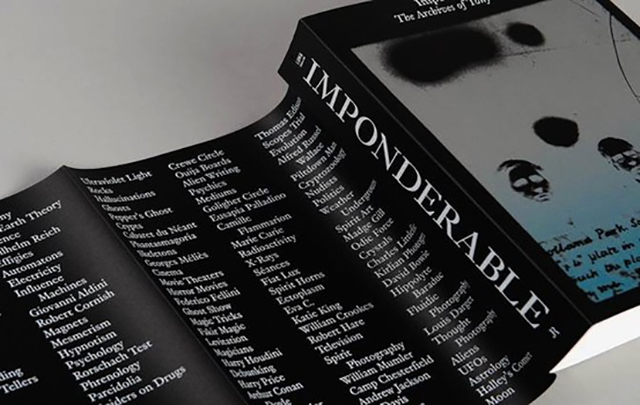

One element of the work that is entirely successful, though, is the accompanying book that MoMA’s put together of Oursler’s personal archives. It contains a lot more material than the first room and it’s impeccably designed. On the back of the jacket, there’s a list of the various materials that Oursler likes to collect and indeed it’s probably best to see the video as a collection as well. A collection of aesthetic and thematic fetishes that Oursler believes have a greater implication for our times than he is able to articulate.

After the video was over, I went to the top floor of MoMA to check out the Bruce Conner exhibition. Conner, a multi-disciplinary artist, was also into witchy, occult-ish aesthetics and there’s a quote listed on one of the works in which he talks about his fascination with religion’s ability to communicate a part of existence that nothing else can. I think there’s something to that and it even carries over to the world’s conjured by charlatans who claim to talk to the dead. They both address our inherent need to feel like there’s more to this physical world than meets the eye. Great art can do that too. But, like a mathematician trying to formulaically prove the phenomenon of awe, “Imponderable” never quite casts a spell.

Comments on this entry are closed.