Hauser & Wirth

Philip Guston: Painter, 1957 – 1967

511 West 18th Street

New York, NY

20 June – 29 July

Philip Guston’s career was characterized by a few Madonna-like reinventions. I’m a fan of his later works, when he retreated upstate and made fun, painterly-figurative canvasses throughout the 1970s. These were mostly pink and playful, the “Confessions on a Dancefloor”of his oeuvre, to keep the Queen of Pop analogy going. Coincidentally, Hauser & Wirth is housed in a building that used to be a gay roller disco.

But the space’s current incarnation as a stern blue-chip gallery is quite a bit gloomier, and the 89 Guston works on view—from the decade-long tail end of his stint as a prominent member of the New York School Abstract Expressionists—are also a lot less fun. Think brooding clouds of fussy brushstrokes in a muddy palette, punctuated by occasional blobs of sap green that looks straight-out-of-the-tube. After the sheer scope of this curatorial endeavor sinks in, even the most devoted Guston fan might find themselves wandering Hauser & Wirth’s cavernous galleries, full of nearly-identical paintings, and asking: is all work by an important artist important?

Well, yes and no. Abstraction fatigue sets in rapidly, and most of the pieces here are repetitive without being disciplined. It works in their respective favors that they mostly belong to different private collections. Viewing them here all at once diminishes the preciousness of any individual canvas—at worst, less refined paintings appear to be studies for the more resolved works in each series. At best, a painting might shine in contrast to its muddier peers.

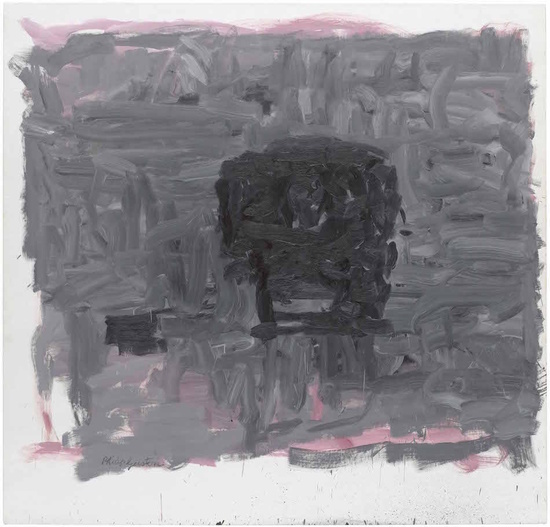

“Portrait I,” oil on canvas, 1965.

Realizing that I was unconsciously performing a series of value judgments on nearly-identical paintings was one of the precious few revelatory takeaways from Painter, 1957 – 1967. Consider, for example, two homologous paintings in a series from 1965: “Portrait I” (above) and “Inhabiter” (below). In the dim lighting of Hauser & Wirth, buried in a series of similar gray canvases, I was convinced “Portrait I” was a far superior painting (it’s less muddy! The brush strokes are more confident! Look at that flirtatious hint of cadmium red!). Later, I considered the charm of a visible process of decision making in “Inhabiter.” The forms are more nuanced; their lack of definition and meandering brushstrokes evidence of hesitancy and revisions. Never had I felt more like the obsequious assistant in The Devil Wears Prada, being scoffed at for her inability to decide between two absurdly alike turquoise belts.

“Inhabiter,” Oil on Canvas, 1965.

So, if you’re looking to re-calibrate your ab-ex appreciation (and really, who isn’t?), the show might be worth a visit before it closes on Friday. But it’s also a reminder of why Guston moved on to fleshy, cartoonish figuration in the last decade of his life—this show inadvertently makes the case that abstraction became a dead-end, or perhaps circuitous cul-de-sac, from which Guston desperately needed an exit. A substantial amount of the appeal here is tracing the development of the mark-making vocabulary Guston later put to better use. Indeed, the highlight is a grid of 48 simple drawings that read as an experiment in drafting a new alphabet. It’s a periodic table of the gestural elements the painter would later synthesize to reactionary effect. In an otherwise arbitrary-feeling exhibition, it feels deliberate and important—and maybe worth one more last-minute trip to Chelsea.

Installation view of Philip Guston’s charcoal and ink-and-brush drawings on paper.

Comments on this entry are closed.