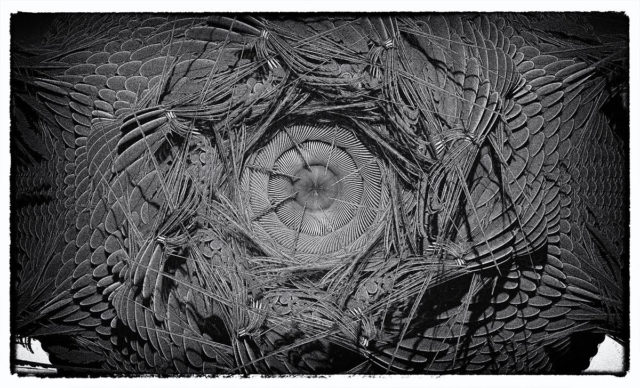

David Chalk, Untitled, digital print (image courtesy Everett Kane)

A Static Revolution

One Art Space

23 Warren Street, New York, NY

On view until August 15

Artists: David Chalk, Carla Gannis, Everett Kane, Peter Patchen, and Claudia Tait

Is digital art alone a complex and multifaceted enough curatorial theme for a group exhibition in 2016?

The medium has undergone a lot of changes in the last few years. The employment of digital methods is now so widespread that it’s almost unavoidable in the contemporary art field. Perhaps because of this, an exhibition based solely on the use of digital manipulations seems redundant.

I discovered this firsthand at the current exhibition A Static Revolution at One Art Space. Curated by Everett Kane, who is also included in the show, the exhibition gathers together five artists who employ digital techniques in their artistic practices to address the effects of digitalization on our lives. The simplistic curatorial focus, coupled with the increasing prevalence of digital art, leaves the exhibition feeling lifeless and rather boring. This provides an unfortunate contrast with the claims to revolution in its title.

To be fair, Kane expresses the desire to push the exhibition’s theme beyond just digital art. The press release ambitiously contextualizes the participating artists’ technological prowess with national politics: “The American election has forced many to revise their concepts of the absurd and the plausible,” it begins. “As questions surrounding the manipulation of government through entertainment deepen so do the politics of image manipulation.”

But this feels like a stretch. While some of the artists present politically-minded work, none of it conveys a practical relationship to electoral politics.

A greater organizational force may be that the majority of the artists in the show including Kane himself, teach at Pratt Institute’s Digital Arts program. When observed through this framework, the show becomes more of a musing on the aesthetic of that particular university program than a universal comment on digital strategies as a whole.

Claudia Tait, Stills Series #1, 2015, digital print (image courtesy Everett Kane)

On first glance, the exhibition appears indistinguishable from any other analogue gallery show. It feels inert. Much of this originates from the overrepresentation of wonky black-and-white digital print abstractions by David Chalk and Claudia Tait. Take, for example, Claudia Tait’s smooth and minimalistic still lifes. On one hand, their strange and ambiguous shapes disrupt the painterly tradition and usual recognizability of subjects like a bowl of fruit. And yet I can imagine a selection of the prints adorning a wall of a nearby office in the Financial District. They are familiar and safe.

The gallery also only includes one screen playing a selection of Carla Gannis’ videos such as her Duchampian Nude Descending A Staircase. Hung near the entrance, the television is separated from the main space of the gallery by a standing wall. This placement is an unfortunate curatorial decision, as it removes the work from a show in desperate need of movement and life.

Peter Patchen’s theramin and “Curiosity” from his Campfire Tales Series (image by author for Art F City)

The only literal static in the exhibition came from Peter Patchen’s theramin, which is part of his Campfire Tales series. Using 3-D printing and e-waste, Patchen mounts a deer head covered in code on a circuit board. The piece combines the natural and digital worlds, as well as references the gruesome trophy-taking impulse popular with hunters. However, the most exciting part of the theramin is that it actually works. Once played, its crackling noise fills the gallery space, adding an auditory and participatory component that livens up an otherwise dead show.

While the show may appear conservative to more seasoned art viewers, I recognize it may be much more challenging to the gallery’s average visitor. One Art Space is located across from City Hall on the edge of Tribeca and the Financial District. I typically associate digital artwork with the Lower East Side or hipper neighborhoods of Brooklyn. In an area where corporate collections reign supreme, the exhibition may be a refreshing change of pace.

Carla Gannis, Selfie Drawing 46 “Zelig,” 2015, digital drawing pigment print (image courtesy Everett Kane)

And indeed, the most successful works in the show thwart the conventions of corporate art. For example, Carla Gannis provided some much-needed satire of our image-obsessed selfie culture. Gannis’ Selfie Drawing 46, “Zelig” presents a combination of the past and the present. Juxtaposed with her use of digital drawing, “Zelig” features Gannis dressed like a turn of the century Gibson Girl with a coiled bun and flowing dress. She poses in front of a mirror holding a large antique camera, taking a vintage selfie.

On closer inspection, the early 20th century wardrobe and equipment gives way to small contemporary details such as white Apple EarPods or a small screen showing her own Nude Descending a Staircase. These sly nods to today’s technology, combined with 20th century tropes, assert that our insatiable urge for self-representation is nothing new. And yet, she also pokes fun at the contemporary material culture we have created to capture our own image like selfie sticks, cellphone cameras, Instagram or Snapchat.

Claudia Tait, Postpartum Boolean series, #1, 2015, crystal engraving (image courtesy Everett Kane)

Unlike Gannis’ exploration of our collective digital self-involvement, Claudia Tait’s Postpartum Boolean series do not, at first, appear especially political. Her small cubes feature ghostly bodies of both infant and mother whether a baby’s head poking out of nowhere or a headless nude woman’s body. These sculptures examine the bizarre physicality and surrealism of birth and motherhood. With women’s bodies an ever-present topic of debate, particularly with the upcoming election, Tait’s series takes on an increasing relevance.

Even Tait’s artistic method references the strange dualism of pregnancy and childbirth. Tait constructed the sculptures using the Boolean function in Maya software. This tool allows for the interaction and intersection between two distinct shapes. In the context of pregnancy and the body, this becomes a symbol of the interlinked and complex corporeal relationship between the bodies of mother and child.

Tait’s representation of the mutability of women’s bodies reflects the most significant point raised by the exhibition. As I see it, A Static Revolution is about the collective transformation of our lives and bodies in the digitized world. However as increasing digitization affects our everyday experiences, it also alters the terrain of the art world. This change necessitates a rethinking of the curation of digital art, requiring more inventive and nuanced themes than seen here.

Comments on this entry are closed.