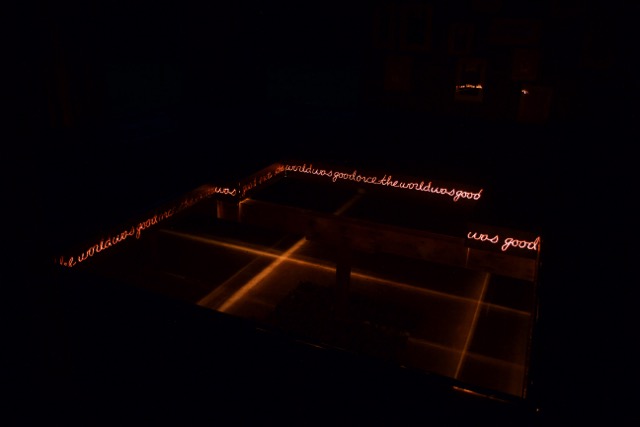

Peering inside Loren Nosan’s The World Was Good Once (Photo by Holden Brown; Courtesy Loren Nosan)

It’s not everyday that you have to sign a waiver before entering an art installation. However, that’s exactly how my trip to Loren Nosan’s The World Was Good Once began.

Turning off a main road, straight into a grassy field outside Wassaic, it became obvious why the waiver and my emergency contact information were necessary. Nosan’s installation is located in a looming, desolate and derelict barn that looks like it went through hell–or at least, a meth lab explosion. Before allowing viewers to look around the show, Nosan pointed out unsound areas of the barn’s floor, which were scattered with holes where the building’s property manager had previously fallen through. Yikes…

Outside of Loren Nosan’s The World Was Good Once (Photo by Holden Brown; Courtesy Loren Nosan)

This adrenaline-inducing introduction to the barn only further strengthened the sense of mystery that pervaded The World Was Good Once. Much of this has to do with the remoteness of the location and the secretive quality of its viewing. The only way to see the installation is to have Nosan and the barn’s property manager take you there. She even asked that I not reveal details of the barn’s exact location in this review. Of course, there’s also no stopping anyone who might wander into the abandoned barn unannounced. Just make sure to watch your step.

Sticking to the official means of viewing, Nosan approximates that only forty people will see the installation in total. This exclusivity, on one hand, limits the potential impact of the installation to just the viewers willing to make the trek. On the other hand, the intimacy and personal connection forged between the viewers and artist–from the car ride to a tour of the space–is unrivaled. There’s no anonymous art viewing here. And this turns out to be a good thing. The conversations about the work become, in some ways, more essential than the art itself.

Loren Nosan, The Weight, 2016, molted emu feathers and foam-coated wire (Photo by Holden Brown; Courtesy Loren Nosan)

Luckily, Nosan’s preoccupation with found objects provides more than enough fodder for storytelling. Multicolored strings hang from a wooden beam in order of their discovery by Nosan. A necklace swung around another beam, jutting from the wall, contains emu feathers gathered from “Mother,” a well-known and much-loved emu formerly living on a nearby farm. Slag from old iron works in the Wassaic area found during construction at The Lantern, the neighborhood watering hole, fills the barn’s basement as a part of a central site-specific solar-powered light installation.

Each chosen material derives from a distinctive time and place in Nosan’s life–both current and past. While most of the materials come from Wassaic, Nosan also displays a cone-like pile of picked-through Wissahickon Schist, the bedrock found in the Philadelphia area where Nosan used to live. Even the barn itself exists as a type of found object for Nosan who became fascinated by its deteriorating architecture after driving by it daily.

Loren Nosan, Shedding of, 2016, snakeskins found on-site (Outside of Loren Nosan’s The World Was Good Once (Photo by Holden Brown; Courtesy Loren Nosan)

Perhaps because of the found quality of the artwork itself, the divisions between Nosan’s art and the objects that originated in the barn are almost indistinguishable. She seamlessly integrates bird nests, artfully torn black plastic window coverings and overgrown vines with her wall of mounted and framed plastic bags and color-coordinated pieces from a television’s motherboard.

In some cases, the line between art and nature is more blurred than others. Take, for example, Shedding of, which consists of two snakeskins pinned to a support beam. Clearing out the barn for installation, Nosan–and a crew of helpful friends and neighbors–shoveled out stacks of wood, dust and a significant amount of various animal droppings. According to Nosan, she found two black snakes when moving a pile of wood. While she never saw the snakes again (thankfully), she discovered two snakeskins, which she then appropriated. The shed skins hang like flags marking the wild presence of nature and its transformations of the space.

Night view of Loren Nosan’s The World Was Good Once, 2016, site-specific solar-powered light installation (Photo by Holden Brown; Courtesy Loren Nosan)

Aspects of the installation, which look like Gordon Matta-Clark-esque interventions, are quirky and enigmatic features of the barn. For example, the light installation The World Was Good Once harnesses the bizarre geometric hole in the middle of the floor that exposes the barn’s basement as a place for a looping ring of the exhibition’s title phrase.

Nosan’s deference to the barn’s architecture and the surrounding natural environment allows for a sense of enchantment as viewers struggle to differentiate planned art from environmental happenstance. I attended the installation with a small group of Wassaic Project board members. Glancing at Nosan’s assemblage Correspondence, which featured two overexposed Polaroids and adding paper embedded with wild mushrooms, one board member asked, “Did these mushrooms grow here naturally?” As Nosan said to me later, “Clearly, they didn’t grow on the paper, but that viewer was willing to make that mental leap and suspend their disbelief. That’s incredible.”

Loren Nosan, Correspondence, 2015, bracket fungus, adding paper and Polaroid photos Outside of Loren Nosan’s The World Was Good Once (Photo by Holden Brown; Courtesy Loren Nosan)

Correspondence was successful in its own right due to the mirroring of color and form between the machine-created exposures in the Polaroids and the biological shapes of the mushrooms. However, witnessing that refreshingly guileless moment between the viewer, art and artist made the piece even more significant, and solidified the importance of the intimate viewing experience within The World Was Good Once. This occurred time and time again within the installation as Nosan illuminated her experiences with each piece. By energizing the work through her own narratives, Nosan shows that, with the right conversations between viewers and artists, this world is pretty good after all.

Comments on this entry are closed.