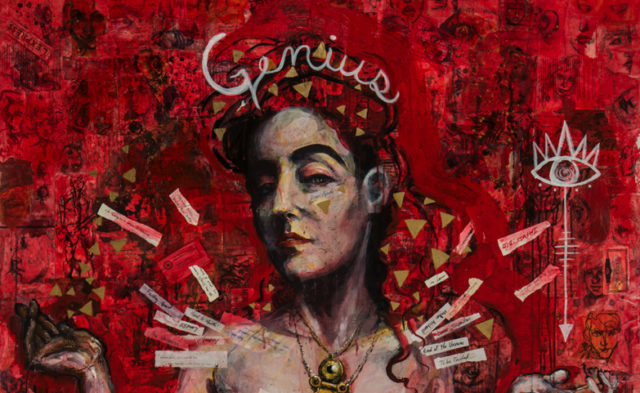

Molly Crabapple, detail of Kim Boekbinder, 2016, mixed media, collage and acrylic on canvas (courtesy the artist and Postmasters Gallery)

Molly Crabapple: Annotated Muses

Postmasters Gallery

54 Franklin Street, New York, NY

On view until October 15, 2016

The relationship between an artist and their muse is one of the most romanticized clichés about art making. Just think of the movie Titanic in which the protagonist, a penniless artist named Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) draws the wealthy first class passenger Rose (Kate Winslet). If you look beyond the tale of class mobility, the artist/muse relationship is one big power trip. And it is the (male) artist who has control.

Molly Crabapple entirely reshapes this relationship for her current exhibition Annotated Muses at Postmasters Gallery. While not as overtly political as her well-known revolution-focused Shell Game series, the exhibition returns agency to the muse, continuing Crabapple’s drive to break repressive power structures. It also allows for an increased intimacy between the viewer and the usually silent, passive muse.

The exhibition consists of eleven enormous, detailed portraits of Crabapple’s influences. The twist here, is that she asks her subjects to alter the work anyway they saw fit before its completion. Most of the muses’ contributions remain mysteriously integrated into the portraits. But, she also had one of her subjects–the porn performer, aerialist and writers Stoya–annotate her monumental Olympia-esque portrait live at the show’s opening.

Molly Crabapple, Stoya, 2016, mixed media, collage and acrylic on canvas (Courtesy the artist and Postmasters Gallery)

As seen in Stoya’s list of qualifications, Crabapple’s muses are not your typical Warholian superstars. They are witches, hackers, sex columnists, sex workers, philosophers, anarchists and revolutionaries. Whether friends, colleagues or role models, her subjects are kickass, unapologetic subcultural figures. And she makes sure you know it by presenting a sentence about each muse below their name on the exhibition’s checklist.

This move toward a multidimensional representation of the muse is further articulated in the portraits themselves, even though it may not be obvious at first glance. From a distance, the eleven portraits look like conventional nudes on vibrantly colored backgrounds. Painting tropes such as drips, scrawled text and collaged paper make these seem like they’d fit right in at a dimly lit burlesque club.

On closer inspection, the portraits are staggeringly complex. Take, for example, Stoya. Here, the larger-scale female figure is actually painted on layers upon layers of drawings of that person on scrap pieces of paper. With countless drawings, she creates an overwhelming and multifaceted vision of the subject at rest, at work, on stage or in their apartments. She also hones in on details of the muse’s body whether their hands, eyes or chests. Rather than offering a singular idealized image, these drawings complicate the portrait, offering a more nuanced view of the muse. However, they are maddeningly obsessive–not to mention classical–figurative drawings.

If you didn’t know these muses were willing participants, you might suggest they file restraining orders.

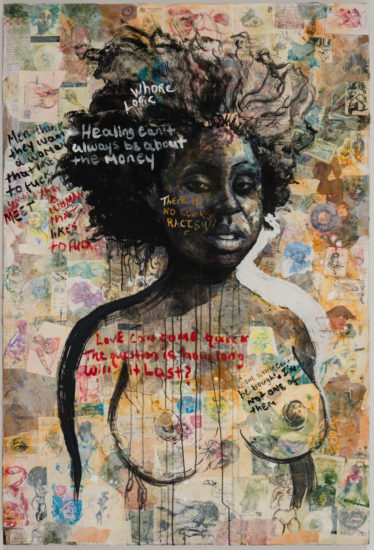

Molly Crabapple, Akynos, 2016, mixed media, collage and acrylic on canvas (Courtesy the artist and Postmasters Gallery)

In many cases, these papers, as well as the rest of the painting, seem to represent something personal about each muse. Take, for example, Akynos’ portrait, which with her direct sensual gaze seems both regal and defiant. Described as a “stripper, sex worker, and sex worker activist–as well as a producer, curator, writer,” Akynos’ background ephemera includes a Do Not Disturb sign and a coaster emblazoned with the insignia from a hotel. Neither of these objects would be alien to sex work and give a possible glimpse into her daily reality.

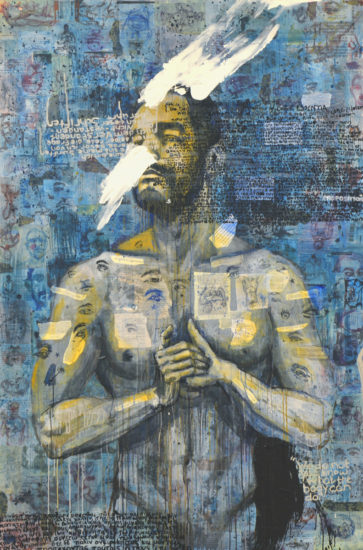

And yet, many of these papers could also come from Crabapple. The portrait of philosopher Fuck Theory, who is the only male muse in the show, features a page from Allen Ginsberg’s seminal poem Howl. Is this an important influence for Fuck Theory’s philosophical work? Or is it an addition made by Crabapple?

This confusion between the muse and the artist and the indefinable additions made by the muses themselves is what make her portraits in Annotated Muses feel just so radical and refreshing. Crabapple blurs the strict lines between the muse and artist, rearranging this long held powerful artistic relationship. She, instead, builds a different and more equal power dynamic between the muse and the artist.

Molly Crabapple, Fuck Theory, 2016, mixed media, collage and acrylic on canvas (Courtesy the artist and Postmasters Gallery)

The upset in the balance of power translates to the viewing experience as well. In order to notice the astounding level of detail, you have to lean in close to these monumental nude bodies. In portraits like Najva Sol, the subject’s bare breasts are almost right at eye level. But you find yourself looking beyond that surface image to the drawings underneath, as well as the text. It’s an incredibly physical and intimate experience that creates a consciousness of the often invisible but palpable influence of the muses’ hand. This allows for a connection between not just the viewer and the artist but also the viewer and the muse themselves.

Annotated Muses isn’t a show that you can take a quick spin around and leave (my typical modus operandi). Crabapple, through her elaborate work, encourages long consideration of the eleven muses. Admittedly, I didn’t know any of Crabapple’s chosen subjects before visiting the exhibition. However, on my return home, I researched each muse, struck by their identities presented in Crabapple’s work. Not only does Crabapple assert that these witches, writers and sex workers are worthy of monumental portraiture–something that might not be that interesting on its own, but she also gives them the power to tell their own story. Or at least, play an active role in piquing the viewer’s interest.

Comments on this entry are closed.