Installation view of Alex Da Corte’s ‘A Man Full Of Trouble’ at Maccarone (Courtesy of the artist and Maccarone, NY/LA)

Alex Da Corte: A Man Full Of Trouble

Maccarone

630 Greenwich Street

New York, NY

On view until December 17, 2016

Now that the country has elected a threatening Wizard of Oz figure for president, any art that takes aim at the myth of American exceptionalism feels pretty relevant. The democratic dream created in 1787 looks a lot like a nightmare in 2016. And with the news of White House staff and potential Cabinet appointments reading like a list of supervillains, it’s refreshing when art can articulate a pointed skepticism of America’s promise.

Alex Da Corte’s A Man Full Of Trouble at Maccarone provides some of that much-needed critique. The work here launches a timely reassessment of America through a combination of its storied colonial past and its kitsch-filled, worn out present.

Titled for a Pre-Revolutionary War bar in the historic district of Da Corte’s native Philadelphia, A Man Full Of Trouble looks as if viewers tumbled with Alice down the rabbit hole. The show is full of recognizable but strangely oversized objects. Da Corte immediately greets viewers with a giant circular sculpture affixed with a laughing blue moon and two black-and-white googly-eyed Kit Kat clocks. Stepping around Blue Moon Tic Tac, viewers find various sculptures scattered around the gallery such as a blow-up cranky-looking pig and a monumental abstracted fluorescent rose named after a P.J. Harvey song.

Alex Da Corte, “The Last Living Rose,” 2016 (Courtesy of the artist and Maccarone, NY/LA)

With this over-the-top presentation and the use of mass-produced materials, the exhibition could easily be brushed off as yet another raising low culture to high art. But, Da Corte transcends these Pop Art clichés by referencing Philadelphia’s fabled colonial and post-Revolutionary war history through his chosen objects. The most obvious example is his A Lily Livered Pitted Pot, which includes a canister of Quaker Oats emblazoned with Pennsylvania’s founder William Penn’s smiling face. Here, Da Corte highlights the transformation of a respected historical figure into a consumerist symbol largely associated with oatmeal. Admittedly, it’s simplistic.

Not all his critical symbolism is that on the nose. Take his grouping of sculptures Luncheon on Eye, which plops ragged dolls on colonial era American furniture. It looks like he robbed the Met’s American Wing before moving onto a thrift store. Of course, an artist can’t use grime-ridden stuffed animals without recalling Mike Kelley. And it would feel downright naive if an artist did unintentionally. For Da Corte, though, this nod seems purposeful. The stuffed animals’ placement in Luncheon on Eye mirror his inclusion of one of Kelley’s sculptures in his spooky exhibition Die Hexe at Luxembourg & Dayan last year. In that show, Da Corte similarly set Kelley’s floppy Arena #8 (Leopard) on a stool.

Installation view of one sculpture in Alex Da Corte’s “Luncheon on Eye,” 2016 (Courtesy of the artist and Maccarone, NY/LA)

Kelley’s visual language provides a key into Da Corte’s thinking. Like Kelley before him, Da Corte sees cheap everyday objects as richly layered symbols, representative of both personal and political narratives. One sculpture of Luncheon on Eye is a fan chair, designed in the late 18th century by inventor John Cram. Da Corte places a slumped over bunny on its seat and attaches knock-off Yeezy heels to its legs. Not only does this weirdly anthropomorphize the chair, but it also combines Philadelphia history with the tacky present day.

The exceptionalism of Post-Revolutionary Philadelphia is repeated ad nauseum to Americans beginning in grade school. These historical narratives are practically legend and continue to affect our delusional electoral politics, seen most obviously in groups like the Tea Party. With this in mind, it’s jarring to see the artifacts from that storied era conflated with discarded bargain bin trash. Not only does it seem like Da Corte points out how far the country has fallen, but it also feels like he’s questioning of the fantasy of America all together.

This juxtaposition between the delusional excitement of discovery (whether inventions or the country as a whole) and a gnawing sense of disappointment or horror runs throughout the exhibition. Even the carpet features an image of people either gasping in awe or screaming. And yet, this critique of the fantasy (or delusion) of America is most compellingly achieved through references to The Wizard Of Oz.

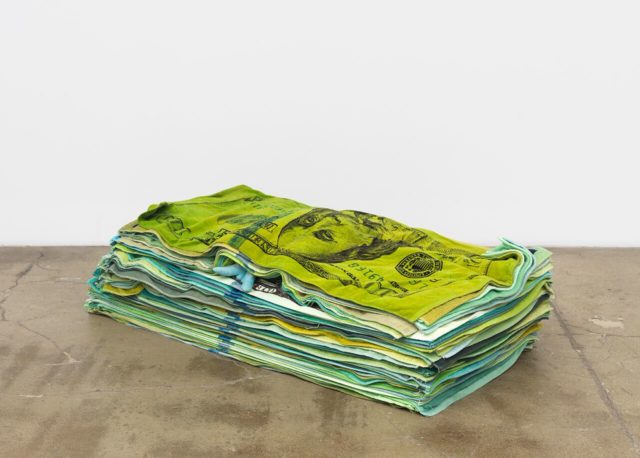

Alex Da Corte, “Stacks,” 2016 (Courtesy of the artist and Maccarone, NY/LA)

Granted, using The Wizard of Oz as a symbol for promise without substance isn’t exactly cutting edge, but here, it’s done so cleverly that it avoids feeling cliché. Take, for example, Stacks. As the title indicates, the work represents a wad of cash in the form of a pile of multicolored towels printed with the hundred-dollar bill. Not losing sight of the Philadelphia narrative, these bills also represent the face of Founding Father Benjamin Franklin.

Viewers could easily miss the key part of this sculpture. On the far side of the piece, angled closely to the corner of a wall, there are two plush feet poking out from the towels. While wearing sensible blue shoes rather than ruby red slippers like the Wicked Witch of the East, this victim’s time in Oz was crushed by the reality of capitalist democracy rather than Dorothy’s house. I know the feeling.

That blow felt hard-hitting in the context of last week’s election The concept of democracy and the constitutional decisions made in the late 18th century in Philadelphia (namely the electoral college) look pretty suspect right now. Da Corte’s show offered some necessary catharsis by throwing subtle jabs at American idealism, and in this fragile transition to Trumpism, I can’t imagine a more urgent message.

Comments on this entry are closed.