“Lady Eleonore Frey II,” 1963.

Otto Dix: Violencia y Pasión

MUNAL Museo Nacional de Arte

Calle Tacuba 8, Delegación Cuauhtémoc, Ciudad de México, D.F.

On view until January 15th

MEXICO CITY-When an artist’s oeuvre zig-zags through five of Western civilization’s most turbulent decades, it’s a curatorial challenge to wrangle it into one solid exhibition. Otto Dix’s work in particular resists a straightforward relationship with the concept of a timeline. His experiences of violence in the first World War remained a fixed psychic scar throughout his career. While dramatic changes in political and economic circumstances influenced his practice, his subject matter and stylistic decisions would often operate in a strangely out-of-synch relationship with art history. Dix’s interests looped back upon themselves and leapfrogged forward—in the 1960s Dix was painting portraits that recalled German Expressionism and brushy abstractions decades earlier in the Weimar Republic.

But Violence and Passion at Mexico’s Museo Nacional de Arte, the ambitious Dix exhibition that closes Sunday, has managed to organize the prolific artist’s work into thematic threads that almost synch up with a conventional understanding of time. Here, galleries containing works that might span decades are arranged around themes related to the socio-political and biographic events that informed them. This curatorial strategy, from Mannheim Art Gallery director Ulrike Lorenz, feels far from heavy-handed. The wall text here gives us factual information about the drastic changes that took place in Germany and Dix’s life, but resists the urge to spoon-feed us interpretations of the artwork. That’s refreshing, as is the fact that not every individual piece here is a standalone masterpiece. The curators have included a handful of works that might be of a lesser caliber than the show-stoppers, but contribute to a better understanding of Dix’s career and thought process.

“Self Portrait as a Target,” 1915.

The exhibition begins with Dix’s 1915 “Self Portrait as a Target,” a somewhat crude piece that sets the tone for the first gallery—a collection of works on paper, mostly etchings, that suggest Dix was unsure of his role as an artist in the war. These pieces range from urgent-feeling sketches of soldiers and corpses on the front lines to political cartoon-like illustrations and almost documentarian pieces. “Landscape: Near Langermark (February 1918),” for example, recalls the art historical genre in its attempt to index reality while simultaneously eliciting an emotional response—here, a sense of dread and regret. If the origins of the Western landscape image were a survey of a patron’s real estate holdings, Dix suggests the apocalyptic fields post-battle were his contemporary Europe’s patrimony.

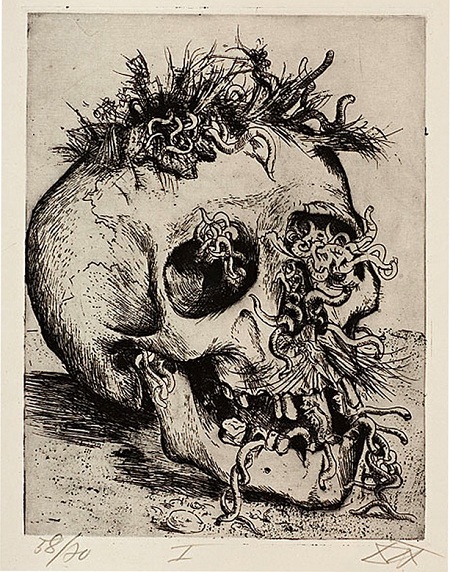

“Skull,” 1924.

Contrast this with his post-war works about the conflict: the macabre is played-up, yet toned-down by a sense of distance and exaggerated horror. “Skull,” from 1924, possesses an almost-punk grotesque theatricality. Notably, works such as these are intermixed in a labyrinthine, intimately scaled gallery. They’re not in chronological order, but arranged to suggest that Dix’s war experiences were an ongoing event in the artist’s life. His horror and fascination with violence stuck with him and manifested in different ways—from empathetic portraits of disfigured veterans to borderline-ironic caricatures of corpses—long after the last treaties were signed.

That interest in the mutable body and violence carries through to the next few galleries, which focus on Dix’s depictions of decadence and crime, mostly painted during the Weimar Republic. Boisterous street scenes comment on the era’s extreme class divisions, capturing prostitutes, disabled veterans, and flâneurs shoulder-to-shoulder on sidewalks. One of the highlights of this series is the 1924 “Front Line Soldier in Brussels”. In this street tableau, the titular figure is positioned off to the side in the shadows. The central figures are painted ladies, retroactively suggesting that sex workers were some of the unsung heroes of the war.

Throughout the 1920s, prostitution and femininity exaggerated to the point of horror became central to Dix’s work. In contrast to his brooding wartime prints, pieces from this era explode with color and diversity of mark-making. His “Sex Murder” series explores the darker side of the era’s promiscuity—each depicts a gory crime scene with violent slashes of paint or pastel. These works brought Dix critical notoriety, but eventually lead to an obscenity trial and dismissal from the Academy of Dresden when the Nazis came to power.

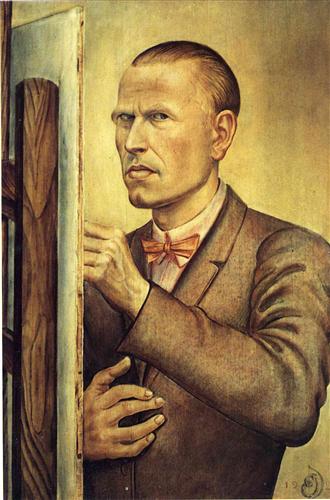

“Self Portrait with Easel,” 1926.

While German artists were facing radical censorship, they were also grappling with the economic repercussions of rampant inflation. This led to a boom in inexpensive watercolor or mixed-media portrait commissions. This history introduces a gallery of portraiture, which again is preceded by an ambiguous self-portrait. Once more, Dix seems unsure of his role in a turbulent time. Straddling the galleries of sexual violence and more conventional portraiture, the artist regards himself suspiciously. Is he a voyeur? Avant-garde political pariah? Or collaborationist portrait painter for the bourgeois?

“Venus with Gloves,”

However Dix viewed himself, it’s undeniable that he was a genius at capturing (or perhaps caricaturing) a sitter’s personality. It’s impossible to pick a highlight from this collection, which includes works from before, during, and after the second World War. The tiny, weird nude “Venus With Gloves,” (1932) is haunting and oddly funny, while “Nelly With Toys” (1928) renders a child as vaguely sinister. There’s a sense of humorous character-probing in each of these, and even his more conservative portraits from the height of repression, such as “Portrait of Emmi Hepp” (1939), speak to a vital ability to breathe life into an artwork despite oppressive situations and material shortages. The realistically-rendered piece stands in stark contrast to his paintings from the previous decade, which explode with color and painterly experimentation. Dix’s 1920s portraits of women in hats, in particular, shine as a testament to wilder times. There’s a sense of sassiness in all of Dix’s female subjects, which radiates from his 1963 “Portrait of Eleonore Frey II,” a large postwar oil painting of the sitter cockily straddling a chair with a cigarette. It doesn’t feel remotely out of place among the smaller watercolors from the Weimar era.

It’s a shock, then, to enter the gallery which exemplifies the sober work Dix produced under Nazi rule. True to exhibition precedent, the room is introduced by the introspective “Self-Portrait with Jan.” Painted in 1930, when Germany was in the throes of depression and the Nazi party first entered the Reichstag, the painting is eerily prescient of the dominant style that would follow. It’s a naturalistic painting of the artist holding up a young Aryan boy and a paintbrush, in front of a pastoral landscape. If the previous galleries revel in the joyful liberation of German New Objectivity’s Left, this one serves as a punctuation mark reminding us of its conservative wing. In this context, “Self-Portrait with Jan” takes on a vaguely foreboding, nationalistic tone. With his paintbrush in one hand, and a stoic look on his face, Dix seems begrudgingly resigned to the role of artist-as-worker in the new coming order. Of course, Dix couldn’t have predicted what Nazi propaganda would look like, but this reads almost as a parody of the party’s aesthetic. It’s a disturbing bit of foreshadowing—a thought that stuck with me as I walked around the gallery of somber paintings, mostly conservative landscapes, searching for potential traces of subversive irony in the work.

“People Among the Ruins,” 1948.

During this time, much of Dix’s earlier work was labelled “degenerate” and destroyed or hidden away. He was forced to promise to only produce nationalistic realist work and was even briefly imprisoned. Entering the “War and Peace” gallery, the last in the exhibition, feels triumphant. Here, Dix’s postwar work exudes a feeling of freedom and liberation. The paintings are painterly once more, bursting with bright colors and a sense of joy. Even the morbid 1948 “”People Among Ruins” feels almost cheery. It’s “Guernica” in technicolor (photography doesn’t do justice to the pigments), a bit gleeful in its rebelliousness, despite its grim subject matter.

Just as the exhibition began with—and was punctuated by—poignantly ambiguous self-portraits, it concludes with one of certainty. Dix’s “Self Portrait as a Skull (Homage to F. Jean Cassou)” was painted in 1968, one year before his death at the age of 77. It’s a fitting capstone to the show, one with a sense of dark humor and an eagerness to look death in the face, quite literally. There are few exhibitions I’ve left feeling so reassured by an artist’s ability to survive and produce despite all odds—and an artist’s acceptance of survival’s limitations.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }