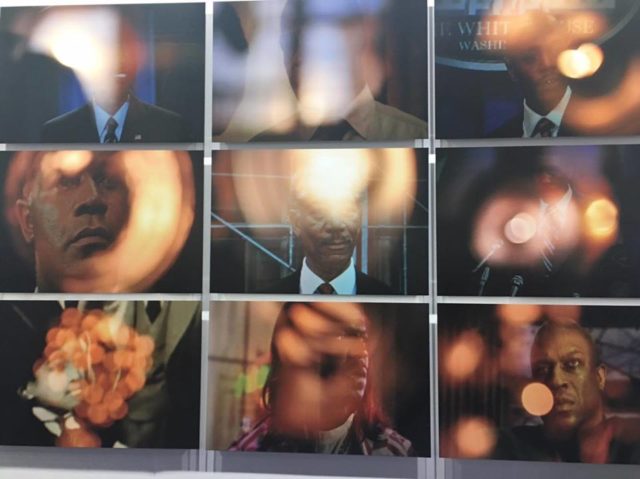

Zachary Fabri, Aureola (Black Presidents), 2012 (photo by author)

VOLTA NY

Pier 90

711 12th Avenue

New York, NY

On view until March 5, 2017

Ten years ago, it seemed most fairs were moving away from the anything-you-can-hang in a booth model to solo show booths. The pinnacle of that movement can be seen as VOLTA, which trumpeted a model in which all booths were solo shows.

Ten years later, how is that holding up? If UNTITLED and SPRING/BREAK are any indication, a preference for curation is on the rise. That’s seen even at shows that boast solo booth models such as VOLTA NY, which is for its second year, hosting a curated section.

As it happens, that section is one of the few reasons I can offer to visit the fair. We could take that as evidence of several things. That the solo booth model has failed. That curation is a better way to organize a fair. That the strategy of hiring an independent curator to assemble a show in which galleries pay fees to have their work included (and take the profit) is a smart way of mitigating these weaknesses. Probably, all of this has some truth.

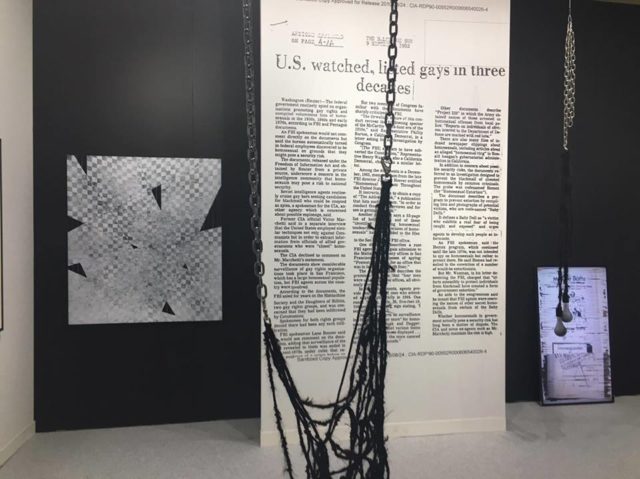

Installation view of Jonathan Ferrara Gallery’s booth (photo by author)

Whatever the case, the big story for VOLTA this year isn’t, as its PR suggests, that it’s celebrating ten years of solo-focused programming, but rather that Your Body Is A Battleground, a central exhibition curated by Wendy Vogel, stole the show. Titled after Barbara Kruger’s iconic feminist work, Vogel gathered a group of eight artists that expand on the media-soaked, identity politics-based artists of the 1980s. Drawing on pop culture, Internet search terms and historical imagery, the selected artists’ biting commentary revealed the ways our culture still deals with legacies of colonialism, white supremacy and misogyny.

View of Y Gallery/Galería Isabel Aninat booth (photo by author)

Unfortunately, though, viewers have to wade through seemingly endless rows of disappointing solo booths—this year’s fair includes 96 exhibitors to be exact—to reach Vogel’s show. Some of these booths featured hoaky takes on historical masters, monumental kitschy renderings of decorative plates and creepy wooden pigeons with cameras for heads. None of which would look out of place at a flea market. Beyond these bizarre inclusions, there was also booth upon booth of unremarkable paintings–tired abstractions, messy figural works and geometric bores. While solo booths can provide the opportunity to place an artist’s work in its proper context, here one work would have been more than enough.

Two works by Pacifico Silano at Rubber Factory (photo by author)

This isn’t to say all the solo booths were misses. In particular, Pacifico Silano at Rubber Factory and Danny Jauregui at Samuel Freeman succeeded at addressing loss, absence and memory in the gay community. They achieved this through appropriation of midcentury gay history such as, respectively, gay porno mags from the 1970s and Bob Damron’s 1965 address book, a covert listing of gay-friendly businesses. Both artists used these images as a starting point to trace the ephemeral legacy of same-sex desire, as well as lost generations of gay men who died in the following decades at the height of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

View of Danny Jauregui at Samuel Freeman (photo by author)

But, apart from these two standouts in a field of close to 100 exhibitors, Your Body Is A Battleground emerged as the main reason to trek all the way to Pier 90. In fact, I experienced a moment of physical relief just stepping inside the show’s purple-carpeted space away from the mediocre booths on the periphery. It was a breath of fresh air.

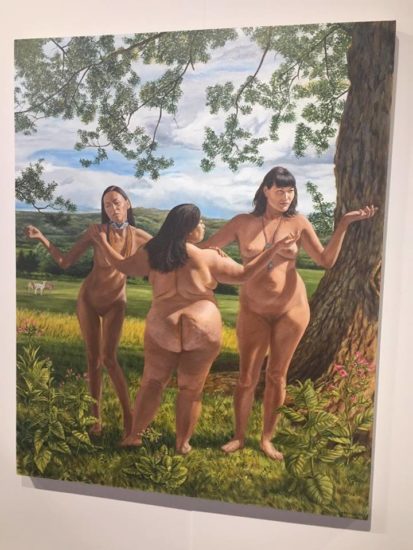

Much of this had to do with the comparative strength and social relevancy of the chosen work. On one wall, Carmen Winant collaged imagery related to the notorious Anita Hill case against Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, reflecting on the troubled depiction of a black woman standing up against a representative of the law. On another wall, Kent Monkman displays monumental pieces inserting the bodies of Native Americans into traditional European historical paintings. Nona Faustine’s series of arresting self-portraits, displayed on another nearby wall, places her nude black female body into locations historically connected to slavery. Standing ghostlike, Faustine becomes the embodiment of the traumatic legacy of subjugation that continues to haunt our current sociopolitical state. Even though all these works take aim at different issues, overall, they came together to form a powerful rebuke of a dominant white masculine culture.

Painting by Kent Monkman (photo by author)

Many of the works employed popular media to discuss the fraught representation of the other. Take, for example, Joiri Minaya’s #dominicanwomengooglesearch, which resembles a strange mobile for a child. Each hanging object is a digital photograph of body parts, hair, tropical plants and festival patterns. The artist culled all these images from a Google image search for “Dominican women.” While fractured and somewhat abstracted, the hanging objects in #dominicanwomengooglesearch reveal the hypersexualized stereotypes and objectifying assumptions about Dominican womanhood.

Joiri Minaya’s #dominicanwomengooglesearch, 2016-17 (photo by author)

Zachary Fabri similarly employs mass cultural imagery to investigate different representations of blackness in America. Due to the sheer timeliness of his Aureola (Black Presidents), though, his work became the standout in an already engaging show. Fabri’s Aureola (Black Presidents) consists of a grid of images of black presidents from popular movies and television shows, ranging from 24 to Chapelle’s Show. The artist rephotographs these characters, maintaining the glare of his camera’s flash. Rather than being disruptive, this flash adds an ethereal quality to the image.

The series gains meaning once viewers recognize the face of President Obama in the top left corner. While most of depicted films and shows dated pre-Obama, Obama’s appearance marks the moment in which the scripted fantasy of a black president became reality. Importantly, Fabri’s series is from 2012, the year of Obama’s reelection. However, looking at the work today, it seems like the dream of a minority president has returned to the arena of fiction yet again. It’s as depressing as it is poignant.

Comments on this entry are closed.