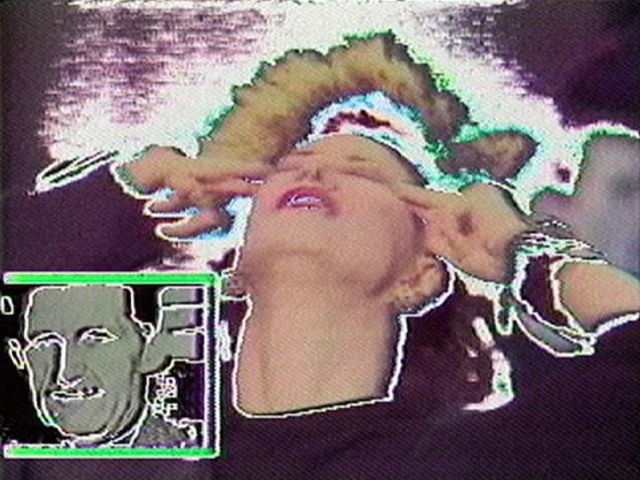

Nam June Paik, Good Morning Mr. Orwell (video still), 1984 (Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix and BRIC)

Public Access/Open Networks

The Gallery at BRIC House

647 Fulton Street

Brooklyn, NY

On view until May 7, 2017

Artists: Alex Bag, Natalie Bookchin, Colab, Jaime Davidovich, E.S.P. TV, Ann Hirsch, Tom Kalin, Jayson Musson, Glenn O’Brien, Nam June Paik, Paper Tiger Television, Raindance, Doug Hall, Chip Lord, Pilot TV, Jody Procter, TVTV, Tony Ramos, Martha Rosler, Jon Rubin, and URe:AD Press | United Republic of the African Diaspora (Shani Peters and Sharita Towne)

Sometimes an exhibition succeeds more as a source of creative inspiration than a collection of timely artworks. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the current group exhibition Public Access/Open Networks at the Gallery at BRIC House.

The show, curated by BRIC’s Jenny Gerow with freelance curators Reya Sehgal and Lakshmi Padmanabhan, gathers historical and contemporary video art that was broadcast publicly whether through public access TV or YouTube. The physical exhibition is just aspect of the show, which also includes an assorted program schedule of screenings, live tapings and symposiums.

The exhibition is far from perfect. Many of the inclusions seem to have aged as rapidly as their chosen technologies, a problem augmented by poor curatorial decisions. That said, these complaints felt like quibbles in the full context of the show. The show’s emphasis on the potential of public channels to bypass institutional hierarchy, reach non-art audiences and motivate political action could not be more crucial. It felt like a blueprint for future radical art making and an urge to rekindle experimentation with technology, even if it, in retrospect, looks silly.

The first thing viewers confront, walking down the stairs of BRIC, is the impossibility of watching every included video. Three long tables of analog televisions sit like an electronic graveyard on one side of the gallery. On the other, numerous projections, flat screen TVs and a Afro-centric living room installation for URe:AD Press showcase more recent work.

The show was so overwhelming I almost left. Presented with a glut of public access materials (the press release boasts over 17 hours of footage), I wasn’t able to fully focus on each video, confronted with numerous other flashing images in my peripheral vision. It made the viewing seem like the physical embodiment of channel surfing as I floated from one TV to another. This limited my experience of the work, which amounted to a scattershot of video clips, and I ended up searching for what videos I could find online once I returned home.

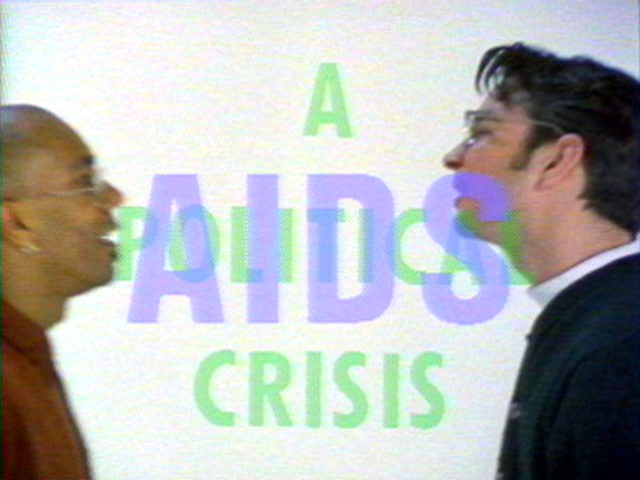

Screenshot of Tom Kalin’s Kissing Doesn’t Kill, 1990 (screencap via Video Data Bank)

Despite the breathtaking amount of videos, the curators managed to introduce the political strength of publicly broadcast art right away with a television screening Tom Kalin’s Kissing Doesn’t Kill. Made for AIDS activist art collective Gran Fury, during the height of the pandemic in 1990, the video features numerous interracial, queer and straight couples playfully kissing. In between these joyful caresses, the artist intersperses slogans like “Corporate Greed, Government Inaction and Public Indifference Make AIDS A Political Crisis.” By appropriating the form of television commercials, the video forces viewers to confront a disease that, at that time, was still rarely addressed.

While Kissing Doesn’t Kill stood as a prime example of how public media could call attention to a dire issue, other works didn’t seem to age as well. Immediately next to Kalin’s video, the curators place Nam June Paik’s Good Morning, Mr. Orwell. The video was broadcast internationally via satellite on New Year’s Day 1984, supported by the NEA (an impossibility today). The hour-long video, hosted by journalist George Plimpton, responded to George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 with short (approximately 3-5 minutes) performances by artists, musicians, dancers and writers, ranging from Merce Cunningham to new wave band, The Thompson Twins. In contrast to Kalin’s still-powerful video, their obsession with satellites seemed goofy. Nevertheless, it contained an underlying optimism with new technology that still felt infectious.

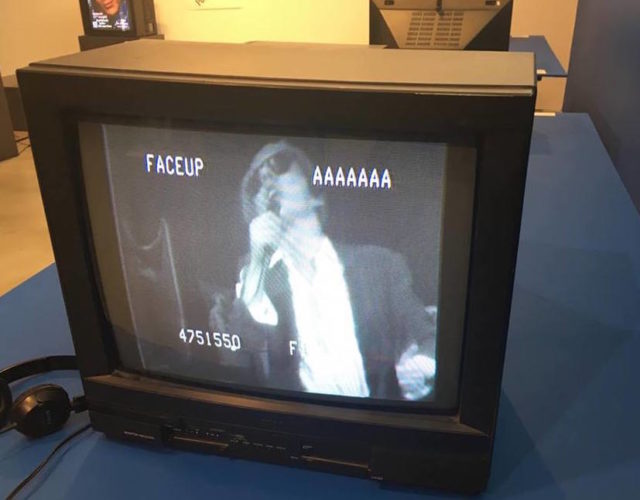

Installation view of Glenn O’Brien, TV Party: The Crusades Show, 1981 (photo by author)

Admittedly, some of my dismissiveness of the videos may have to do with the curators’ frenetic method of presentation. What might have felt radical and rebellious in the 1970s and 1980s on late night television fell flat in a gallery, particularly one chock-full of videos. Cave Girls by Colab (Collaborative Projects, Inc.), a fantasy of a pre-historic all-women culture conceived of by Kiki Smith and Ellen Cooper, just looked like artists romping around a primitive environment to The Bush Tetras and Y Pants’ funky beats. Similarly, Glenn O’Brien’s wacky TV Party, a public access New York cable show featuring Downtown stars like Blondie, Fab 5 Freddy and a young Jean-Michel Basquiat, seemed like a party viewers weren’t invited to. For example, in “TV Party’s Crusades Show,” O’Brien, with a colander on his head, tries (and fails) to act as ringmaster to a chaotic ever-rotating set of musicians in medieval costumes that seem to do more wandering on and off set than playing. It’s annoying.

Screenshot of Ann Hirsch’s “Caroline + Crystal Castles” from The Scandalishious Project, 2008-2009 (screencap by author)

Much of the contemporary work didn’t fair much better, as seen in Ann Hirsch’s YouTube-based The Scandalishious Project. Made between 2008 and 2009, Hirsch constructed a viral video personae Caroline. Caroline, in her clips, dances, writhes, head bangs and fist pumps to Miley Cyrus and Crystal Castles while occasionally dedicating the dance to her latest crush. On one hand, it’s dumb by design–a send-up of the baffling fame of YouTube stars. While the videos felt dated, a product of the relative calm of the Obama years, Hirsch’s videos also projected an almost utopian view of technology and the unexpected audience it could possibly reach.

Taking a step back, though, the individuals works, in the context of the show, succeed at asserting the continually evolving artistic drive to reach audiences through popular and public means. Even Paik’s video showcases the possibility of affecting a random international viewership (the same could be said of Hirsch and other works in the show). Overall, Public Access/Open Network importantly reveals how to move beyond traditional institutions and their limited definition of success and viewership.

Screenshot of TVTV’s Four More Years, 1972 (screencap by author)

This strength came into focus with works like TVTV’s Four More Years, which directly points to ways to infiltrate contemporary politics. A cultural collective based in San Francisco, Top Value Television (TVTV) took on Republicans, as well as the limited narratives in traditional media, by covering Richard Nixon’s appearance at the 1972 Republican National Convention. TVTV, in the video, interviewed decidedly minor and somewhat mundane figures like other newscasters, event organizers and random supporters. They also featured extended shots of enraptured and rabid-looking Nixon supporters, which had an eerie resonance with the cult-like behavior of Trump supporters today.

And this inadvertent comparison raises compelling questions about the impact similar artistic political infiltration and experimentation with technology might have today. What if an artist filmed the 2020 Republican National Convention? Or even now, what if a collective got their hands on a White House press pass and turned Sean Spicer’s chiding press conferences into an art piece? The possibilities for political action via public domain, as shown by Public Access/Open Network, appear endless and all seem to suggest that our revolution could still be televised.

Comments on this entry are closed.