LOS ANGELES- Someone once described L.A. to me as feeling “less like a city, and more like post-apocalyptic suburbia.” Given the doom-and-gloom tenor of national political and global crises, it’s no surprise that this place has become such a topic of fascination for the art world. Below its veneer of conspicuous consumption, it’s a city known for cults, secret societies, and a near-Biblical litany of pending natural and climate-change-related disasters. Los Angeles is where the American Dream was symbolically forged, and unravels splendidly. I can’t think of a better artist to inaugurate an institution here—one housed in a trippy, abandoned 1960s Masonic lodge, no less—than longtime Angeleno Jim Shaw.

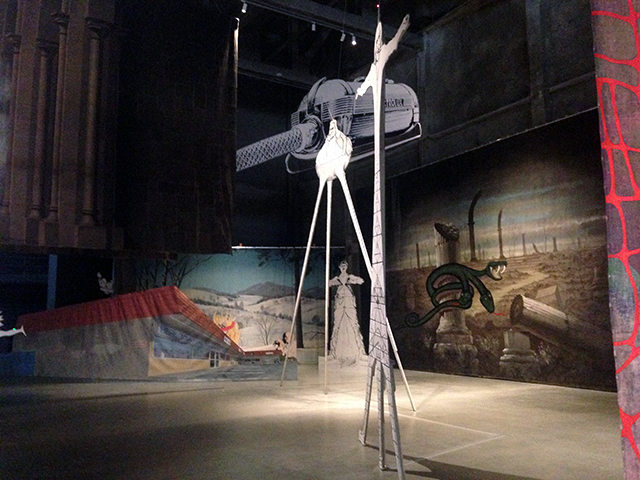

Jim Shaw: The Wig Museum, now on view at the new Marciano Art Foundation, is the all-too-rare exhibition that feels 100% true to an artist’s oeuvre and 100% appropriate to its context. The immersive installation reads like the bookend to Shaw’s triumphant retrospective The End is Near at the New Museum in 2015—here, in 2017, The End has arrived. Shaw continues his tactic of modifying theatrical backdrops and found scenery with pop-apocalyptic imagery. Think a labyrinth-like stage set populated by comic book heroes in states of distress and fireballs and you get the idea. It’s the perfect counterpoint/compliment to the pomp and ritualistic theatricality of the museum’s Masonic digs.

The 100,000+ square foot building, which still bears many of its original occult details, is home to the collection of Maurice and Paul Marciano, the brothers who built their fortune through GUESS Jeans.The architecture firm who oversaw the space’s transformation, wHY, described their vision as “an art playground” and that description isn’t a stretch. The building itself is exceptionally strange, and much of the best work here has been curated/created in response to its idiosyncrasies.

In an earlier post I discussed, for example, site-specific pieces by Alex Israel and Ryan Trecartin with Lizzie Fitch in the mezzanine and second floor, respectively. But the loot left behind by the Masons themselves almost steals the show. Masonic rituals apparently involved plenty of pageantry. When they vacated the building in 1994, they abandoned decades worth of elaborate theatrical sets, wigs, costumes, and other ephemera including a series of busts illustrating racial categorizations. Some of this material has been integrated into Shaw’s installation, alongside pieces from his own collection, Shaw works the Marcianos had purchased, and new site-specific interventions.

The haunted-house like experience, depending on one’s point of entry, begins with a beauty-shop-like storefront. Outside, two powdered wigs evocative of the kind of power societies such as the Masons represent—institutional, white, male, and rooted in tradition—are housed in pillar/vitrines supporting the structure’s roof. (Perhaps a Biblical allusion to the chained Samson, shorn of his locks?) The inside, however, houses an outlandish collection of hairpieces that seem to reference drag and African American hair culture, as well as elemental goddess figures. It feels like a celebration of the old guard’s eccentricities giving way to those of ascendent (or pagan) cultures.

That sense of “the decline of Western Civilization” as we know it is reinforced throughout the labyrinth. Comprised of found theatrical backdrops alongside Shaw’s own original works, the installation might feature a kitschy set piece from the 20th century depicting the apocalypse alongside the artist’s own vision of the end of the world. In one tableau, a demonic serpent is coiled around crumbling doric columns in a ruined neoclassical wasteland. Shaw juxtaposes this with his own backdrop—a suburban strip mall in flames, anarchy signs spray painted over the storefronts.

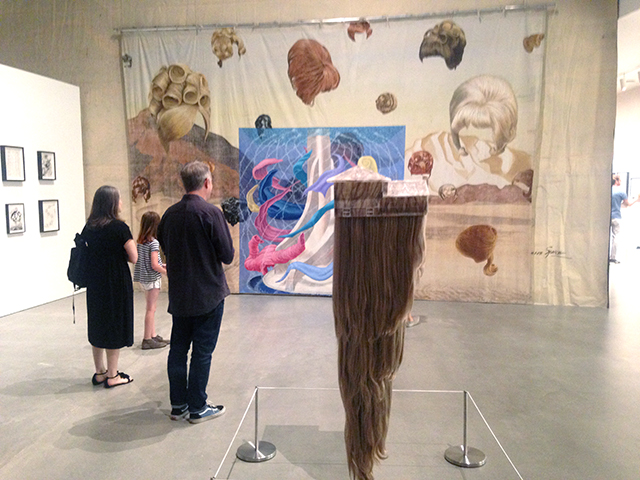

The amount of detail and sense of completion in both the found sets and Shaw’s own interventions is remarkable. In one wall-sized canvas, a series of delicately-rendered wigs evocative of the 1960s sitcom ideal rain down into a barren desert. Nearly every individual hair is legible, rendered with precision brush strokes. In front of the painting, a sculpture of a suburban dream home floats precariously. It’s cast from wax and impossibly long hair, which trails out of the bottom like roots breaking through the foundation. The house itself becomes a wig—an icky identity to be tried on like so many fad hairstyles.

For all the doom and gloom depicted here, the show does indeed feel like “an art playground”. That’s due in part to Shaw’s smart sense of satire, but also to his skill at balancing scale in both his found and original works. There’s something actively engaging about the mastery of stylistic remixing here—a thrill to discovering a tiny detail in a chaotic, Hieronymus-Bosch-like tableau that’s complementary to the immediacy of the more graphic works. At no point as a viewer did I feel bored, whether browsing smaller framed drawings or navigating the labyrinthine installation. That’s something that’s hard to say about many museums. What Shaw captures is a sense of absurd wonder, and one gets the impression that we’re sharing in the artist’s own revelment at the bizarre rather than having it performed for us. That’s a feeling I encountered several times in the Marciano Art Foundation—from Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s residency/video installation to the multiples and zines for sale in shop. There’s a surprisingly playful, artist-centric approach to the nascent institution’s program, and it’s encouraging to see the Marciano Art Foundation living up to its promise thus far.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }