[Editor’s Note: IMG MGMT is an annual image-based artist essay series. Today’s invited artist, Marc Handelman, lives andworks in Brooklyn, NY. He has exhibited his work at venues such as The Royal Academy of Arts, PS1 Contemporary, and the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art. He is represented by Sikkema Jenkins & Co. (NY), where he had a two person exhibition in the spring, and Marc Selwyn Fine Art. He is a faculty member of the Bard MFA program.]

Turner’s art is still governed by the same rules as the art of his predecessors: even clouds have to be put in perspective; and if one pretends that they present a flat basis, it is easy to set in place a grid”¦that will show how they should be disposed.

-Hubert Damisch, A Theory of/Cloud/Toward a History of Painting1

Sky is to the 20th Century what landscape was to the 19th Century.

-Aphorisms, Jack Goldstein.2

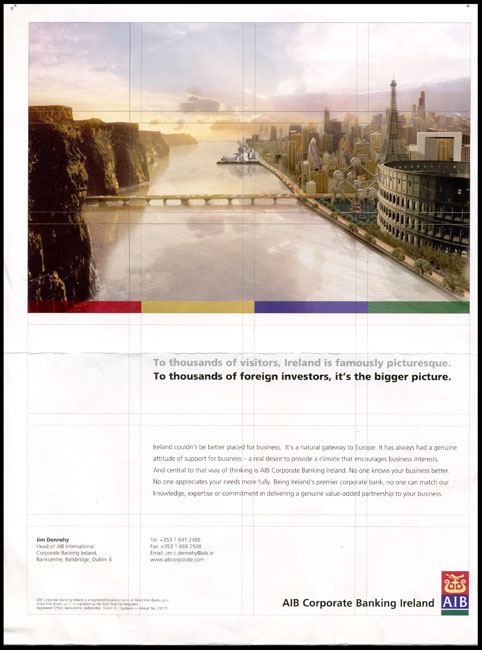

Over the last several years, I’ve thought a lot about the ways in which we continue to re-stage the landscape as a pictorial and historical trope. I became interested in the representation of the sky as a surrogate for many of the functions traditionally carried out by Landscape in the 19th century.Among these was the way nature was enlisted as a foil for ideology thereby making its representational conventions appear natural. The landscape also situated the viewer in different spatial configurations, shaping relationships to new possibilities of sight, knowledge, and power.

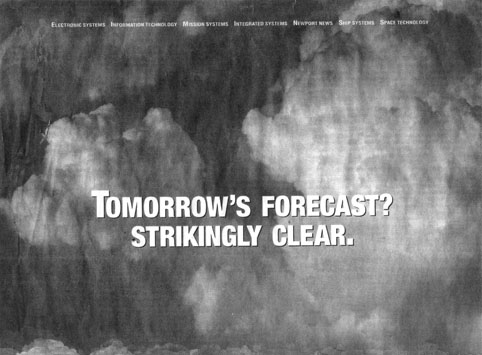

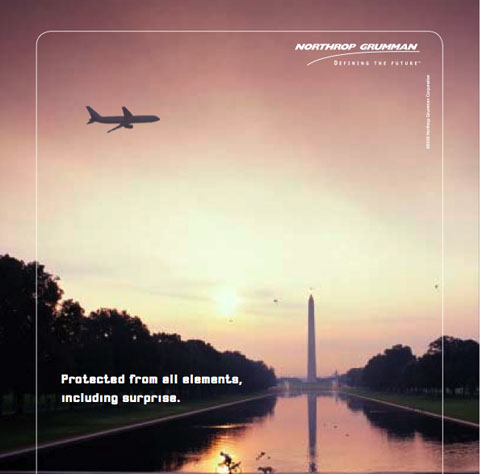

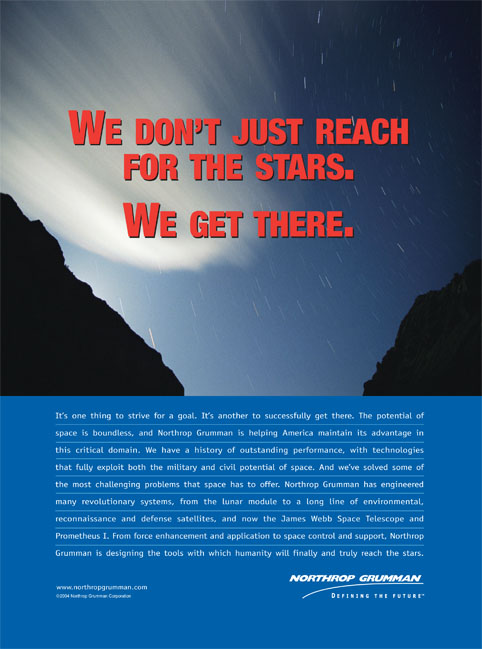

My focus on the sky began when I came across a full-page image in the newspaper (above.) A large cloud cycle, reminiscent of one of Constable’s studies, rose toward the picture plane behind large block letters reading: “TOMORROW’S FORECAST? STRIKINGLY CLEAR.” It was an advertisement for a defense corporation named Northrop Grumman. The image recalled countless 19th century paintings of the Natural Sublime: the thunder-clap from the mountain, a turbulent sea, the terrifying awe of an abyss-like valley, and the approaching storm.In the 19th century, the aesthetics of the Natural Sublime, espoused by the philosopher Edmund Burke a century earlier, took hold of the American cultural and political consciousness. The experience of the sublime registered a sense of terror by an encounter with an external power –such as the storm. This natural force was imbued with the power of God. Surviving the potential for annihilation, terror was transformed into sensations of awe, pleasure and reverence. The Oxford Dictionary provides this definition: “Of things in Nature and Art affecting the mind with a sense of overwhelming grandeur or irresistible power; calculated to inspire awe, deep reverence, or lofty emotion by reason of its beauty, vastness, or grandeur.”3

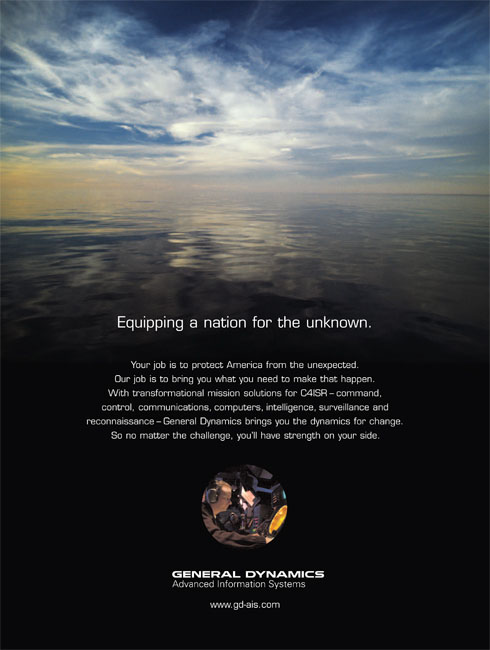

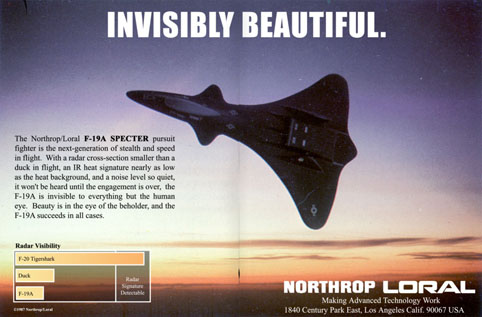

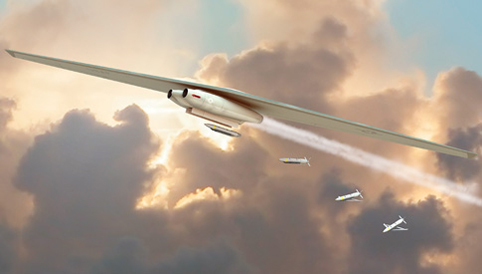

Drawing on this older image of the sublime, the defense corporation’s slogan evoking “weather control” suggests, by contrast, a control of external power. Here, this image of a turbulent sky –also reminiscent of the engulfing dust cloud billowing down Wall Street during the collapse of the World Trade Towers –seemed to function as a metaphor for terrorism. Northrop Grumman, far from predicting the weather was aligning itself with a God-like force, suggesting it wasn’t just powerful enough to control nature, but powerful enough to be Nature. Here, it would ostensibly master this force that was once the Other. The cloud eerily began to take on the explosive smoke of an air strike–, the technology for which was the real, yet invisible form of agency for sale.

Since seeing the Grumman ad, I began collecting images related to the sky in advertising, art history, and popular culture to examine the myriad ways the sky currently functions in visual culture. I also wanted to investigate how its functions differ and relate to those of 19th century American landscape. It seems that a broader trope of “weather control” in the Grumman ad, and numerous other images, epitomizes a re-configuration of the Sublime.

In the late 18th century, the philosopher Emanuel Kant had adopted Burke’s ideas on the Sublime. Unlike Burke’s sublime where feelings of terror and awe remain tied to an external object (such as the approaching storm) Kant argued that the faculties of Reason could enable us to overcome this initial feeling of terror to recuperate an internal sense of power and superior self worth. In the words scholar John Goldthwait “”¦the feeling of the sublime is really the feeling of our own inner powers, which can outreach in thought the external objects that overwhelm our senses.”4

Many of the images I have been collecting draw on this sense of the sublime and its affects of empowerment. Part of this new aesthetic sensibility would develop in America from the mid-19th century onward.Here the religiosity of the Natural Sublime would be infused with these burgeoning feelings of agency and a ‘picture’ of nature as a force to be dominated. In landscape painting, this new aesthetic experience was developed through an elevation of the viewer/spectator from the reverential position of the valley to the godhead of the mountaintop.

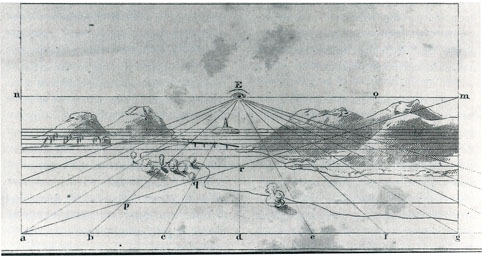

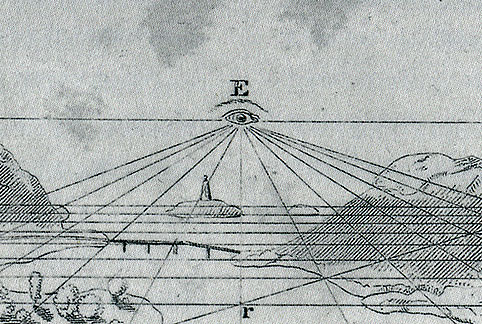

Method of drawing an elevated perspective view from a topographical plan, 1837. (DETAIL)5

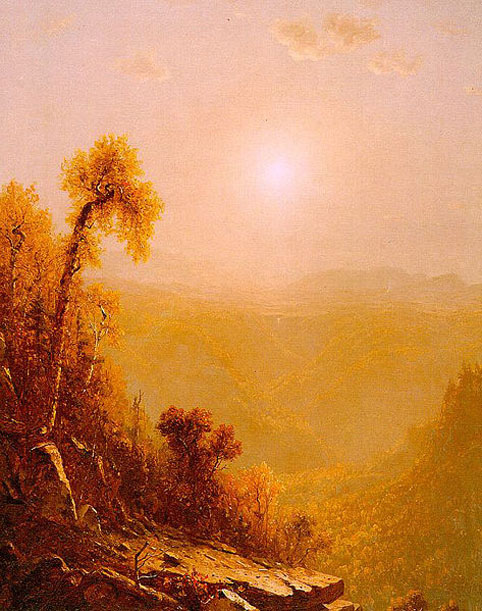

In late 18th and early 19th century European landscape painting, the viewer was often situated in the valley below looking with a “reverential gaze” towards the sun, mountaintop, or heavens —all of which were symbols of God. American landscape paintings from the mid-19th century onward, elevated the viewer situating his or her vantage point high above in both a spatial and symbolic inversion of power. Here, the sun — the locus of sight and power that was once a vanishing point, symbolically transfers to the retina of viewer whose gaze now emanated outwards across the landscape in a panning arc. The subject now looked from the mountain-top out onto the world. From the ostensiblesummit, as historian Albert Biome writes,“[this] magisterial gaze assumes a perspective akin to the divine.”6

Typical in many American landscapes of this period was the stage-like depiction of the foreground, middle-ground and back-ground as spatial equivalents for the past, present and future. While the foreground frequently depicted an uncivilized and “savage nature,” the “middle landscape” showcased an idealized time, often picturing a domesticated landscape, the stirrings of a small town, or a railroad heading west. The higher elevation allowed one to see further into the distance, pushing back the horizon, and catapulting the American frontier back into space as if one were able to see even further into the future. In these paintings, the ‘civilizing of the wilderness’ through colonial development also functioned in part as a mask and proponent for an Indian genocide being waged on the continent. Here, “the idealization of nature concurrent with industrialization; confidence in an inevitable future and a selective memory of the past,” constituted a moralizing narrative of conquest structured pictorially through space and time.7

The increased prominence of the sky also displaced the “geological-time” described by the physical landscape with a sense of infinite time. The sky’s unrelenting movement and disregard of what transpires below, helped picture a “natural” and totalizing sense of inevitability to the shifting political, historical and territorial contours on the ground. It achieved this end by alluding to a sense of timeless providence and historical predestination that was a residual strain of protestant theology in the American imagination. These aesthetics were inscribed within the ideology of “Manifest Destiny,”through which the conquest of the continent was sanctioned under a divine mandate, and an emboldened sense of entitlement and ownership.

The repetition of this gaze would play out in canvases of popular artists of the day, from 19th century American painters such as Frederic Church, and Albert Bierdstadt, to Sanford Gifford. American artists of the mid-19th century continued to draw on other European representational-landscape idioms such as the Picturesque, as sources of political and historical legitimization.While distinctly American, this “magisterial gaze” would later become an increasingly ossified but potent representational regime within the broader fabric of national-corporate Empire.

As for the picture of the American landscape itself, this index of national borders and identity was already a fictional hybrid of other terrain, assembled sketches and reproductions. In this shift then from the landscape to the sky, and from a subject position of reverence to one of assumed power, an entire series of images of the American imagination would be consolidated in the space of the heavens. From the height of these paintings popularity and relevance, one hundred and fifty years later, we still seem to be invested in the mechanisms of their representational logic.

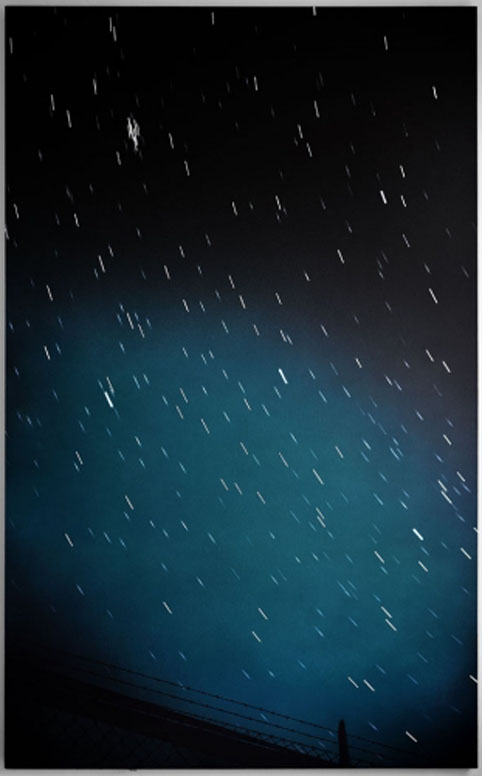

Throughout the 20th century, the viewer continues to be elevated, in greater conquests of space, nature, feats of technology and experiences of sublimity. But if the metaphor of “weather control” in the 20th century, reflected in Kant’s ideas about the sublime, suggests an even further internalization of our sense of empowerment, the work of artist Jack Goldstein (1945-2003) proposes a condition of far less agency. In his aphorism, “Sky is to the 20th Century what landscape was to the 19th Century,” the sky takes on the same imperialistic functions as the landscape had previously.

But the known skepticism within Goldstein’s work —that we are often beholden to the very images we seek to functionalize — might suggest we take the glibness of this aphorism as a provocation. Perhaps we should see our figurative elevation as a kind of regression. Kant had argued that the awe engendered by sublime objects would ultimately lead to a greater sense of agency and moral worth. But the experience of the sublime was increasingly instigated and manipulated by man-made objects to inspire different fears and desires. As Historian David Nye explains, “[This] nineteenth-century technological sublime had encouraged men to believe in their power to manipulate and control the world”.8 One could imagine that for Goldstein the sky is simply the same image –the slight tilt upwards of the same camera from the same vantage point. However elevated, our sense of agency is an illusion of the forces and images we supposedly master.

Jack Goldstein loved a good picture of the sky. His images often drew from the language of film and advertising, from the splitting of the atom to the vectors of a satellite’s scopic vision. These would illustrate a new kind of landscape and a different series of spaces and forces to dominate and control. But more than anything else, his images would picture the visual mechanisms of representation itself. The sky became for Goldstein something of a placeholder; a focused consolidation of spectacularized effects from the 20th century.

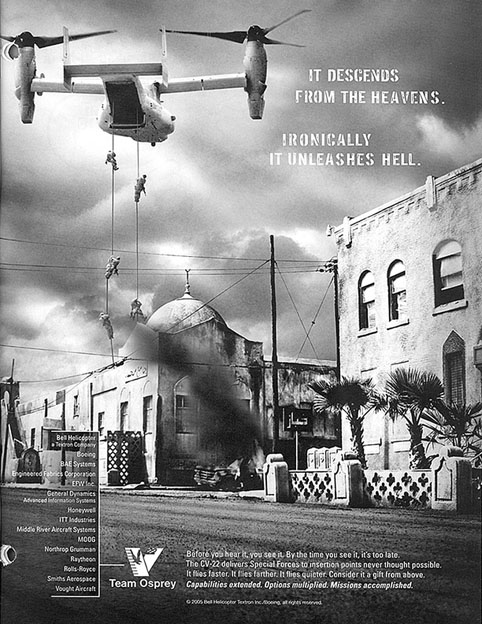

Situated between the 19th and 20th century’s respective representational paradigms, the skyscape borrowed both the dramatic special effects of film and the visual affects of the sublime within landscape painting. Goldstein would write that his skyscapes “”¦are like movie-sets that showcase special effects as edited from a world narrative.”9 In many of the skyscapes of the 20th century, the sky would cease to function as a mere backdrop, but take on a central role becoming an ostensible protagonist of visual and rhetorical effects.

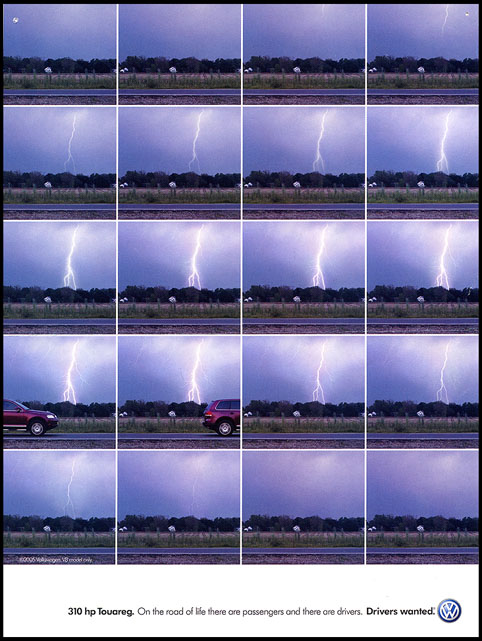

If landscape painting of the 19th century might be thought of as an empty stage —-then the sky of the 20th century could be described as the primary protagonist. In other words the sky’s inherent, light, vapors, emanations, and movement would assume center stage . In images from advertising to Hollywood, the sky’s seductive and dramatically programmed effects would shape the scene, the topography and most significantly the viewer. It created new forms of corporate, political and national identity. The sky, as it were, was never a passive backdrop, but always an apparitional figure to its supposed ground.

On the surface, Goldstein’s aphorism seems to suggest that we simply performed an imagistic-makeover. The heavens and their pictures, would be imbued with god-like forces. In these new images, we would witness not the power of nature itself, but the sublimity of our special effects, technology and optical devices. We’ve always desired this sense of empowerment. It is no surprise then that today, one of the commonly asked questions at the visitor center of the Grand Canyon by awestruck tourists is —“What tools did they use?”10 This assumption of human agency, betrays a hubris absent in the sublimity of an external nature. The sky has become the reigning emblem of our sense of power.

But Goldstein’s serial showcasing of effects and tools of representation implicates our very sense of self and empowerment as a constructed effect. This illusion is simply just another “image.” Perhaps the desires propelled by our pictures betray something close to that earlier Burkean state of reverence to an external force and power —-to love and hold in awe the thing that dominates and exploits us. We might feel as though were at the apex of our ostensible summit, but we remain subjugated in the valley below.

Today, images of the sky remain ubiquitous. It is the oft-used trope of corporate aesthetics, the vision of the guided missile, the romantic “delivery—device” of the ad, and the placeholder of every tourist vista point. What has fascinated me since stumbling upon the Northrop Grumman ad is the extent to which Goldstein seems to be right. The image of the sky as a new kind of regime within the field of representation, has done one thing very well– namely, make us feel, and desire to feel, that we are in control, —-as spectators, as owners, as consumers.

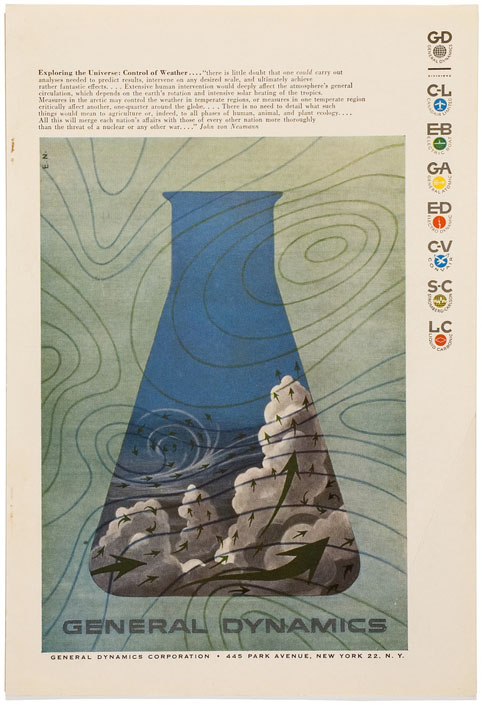

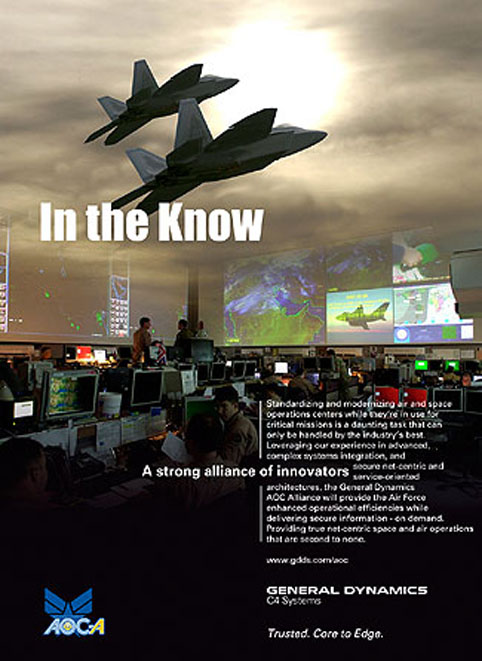

The remaining selected images below draw heavily on corporate marketing, many of them from the defense industry for which the Grumman ad was a catalyst. Here in particular, there’s an elucidative correspondence between the externalized or absent violence of these ads and the obfuscated violence of their Romantic analogues in 19th century American landscape painting. – Strange too, in other contemporary images of the sky, is the sustained rhetorical integrity of many Luminist painting conventions. They picture the quiet, frozen anticipation before the storm and intimations of doom behind the surface of a crystalline world.

All of these images then, are a constellation of skies, gazes and propositions. Like Goldstein’s movie-sets, these ‘ostensible paintings’ might be thought of as stills from our world narrative, or better –its trailer.11

Penelope Umbrico, Sunburn, (Screen Saver)

- Hubert Damisch, “A Theory of /Cloud/ Toward a History of Painting”, Stanford Press, 2002, P, 191 [↩]

- Jack Goldstein, Aphorisms, “Jack Goldstein, Films, Records, Performances and Aphorisms 1971-1984” Catalogue: Galerie Bucholz, Koln, and Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig, Koln, P.22. [↩]

- David E. Nye, “American Technological Sublime”, MIT Press, 1994 [↩]

- David E. Nye, “American Technological Sublime”, MIT Press, 1994 [↩]

- Treatise on Topographical Drawing, by Seth Eastman (New York: Wiley and Putnam, Plate 6). from Albert Biome: “Manifest Destiny and American Landscape Painting c. 1830-1865, The Magisterial Gaze”, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991, P. 24. [↩]

- Albert Biome, vividly constructs this historical shift from the “revenential gaze” to the ‘Magisterial Gaze” in “Manifest Destiny and American Landscape Painting c. 1830-1865, The Magisterial Gaze”, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991, P.22. Angela Miller also describes an analogous configuration in an essay on Thomas Cole in his situating of the “agricultural prospect” far below cycles of “meteorological drama.” “The effect of this sudden drop [of the valley] is to create a sense of rupture which is not only spatial and aesthetic but also historical, separating a nature viewed as a self-generating realm from one that, by being “domesticated” is also deprived of any agency distinct from the human and social forces that colonize it.” Angela Miller, “Empire of the Eye, Landscape Representations and American Cultural Politics, 1825-1875”, Cornell University Press, pp. 44-45. [↩]

- Barbara Novak is one of the few historians whose work on this period of American Art has used the contested terms “genocide” and “evil” to frame and evoke an historical paradigm with links to our own. “The taking of the continent was powered by an undisputed Christian consensus, a missionary zeal, a largely benign interpretation of progress. The themes are contradictory: the growth of acomfortable middle class and an on-going Indian genocide; the idealization of nature concurrent with industrialization; confidence in an inevitable future and a selective memory of the past.” “Nature and Culture, American Landscape and Painting, 1825-1875”, xii. [↩]

- “Kant had reasoned that the awe inspired by sublime objects would make men aware of their moral worth despite their frailties. The nineteenth-century technological sublime had encouraged men to believe in their power to manipulate and control the world.” David E. Nye, “American Technological Sublime”, MIT Press, 1994, P. 295. [↩]

- Jack Goldstein, Aphorisms, “Jack Goldstein, Films, Records, Performances and Aphorisms 1971-1984” Catalogue: Galerie Bucholz, Koln, and Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig, Koln, P.22. [↩]

- David E. Nye, “American Technological Sublime”, MIT Press, 1994, [↩]

- I’m alluding here to Jack Goldstein’s most famous aphorism: “Art should be a trailer for the future.” First published in: Documenta 7, Exhibition Catalouge, Kassel 1982. [↩]

{ 8 comments }

Excellent essay. I’m reminded of the “Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting” exhibition at the Tate Britain, where a section grouping together landscape paintings evinced something like this shift, albeit one more explicitly political and colonial, and with its own specific “moralizing narrative of conquest,” and aestheticization of power. There is one painting in particular, Richard Carline’s 1920 “Damascus and the Lebanon Mountains from 10,000 feet”, borrowed from the Imperial War Museum. It prefigures the opening shot from Triumph of the Will, giving us a highly precise bombardier’s gaze over a landscape whose exotic difference is sanitized and contained by a forcefully modern mode of representation. The sky’s physics take on a completely different charge, as the invisible pressure that holds aloft the invisible airplane, as the matrix for a new type of gaze.

http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/britishorientalistpainting/explore/landscape.shtm

Excellent essay. I’m reminded of the “Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting” exhibition at the Tate Britain, where a section grouping together landscape paintings evinced something like this shift, albeit one more explicitly political and colonial, and with its own specific “moralizing narrative of conquest,” and aestheticization of power. There is one painting in particular, Richard Carline’s 1920 “Damascus and the Lebanon Mountains from 10,000 feet”, borrowed from the Imperial War Museum. It prefigures the opening shot from Triumph of the Will, giving us a highly precise bombardier’s gaze over a landscape whose exotic difference is sanitized and contained by a forcefully modern mode of representation. The sky’s physics take on a completely different charge, as the invisible pressure that holds aloft the invisible airplane, as the matrix for a new type of gaze.

http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/britishorientalistpainting/explore/landscape.shtm

Nice and fairly chilling collection of defense ads. Relating them to the 19th Century sublime and proposing a perspectival tilt from terror to Godlike control is an ambitious thesis I’m not sure is proven here. The Constable clouds from the early 1800s are also seen from above. And you can find Church and Bierstadt examples where the perspective is from down below. it shouldn’t surprise us that ads for air force defense contractors prominently feature skies. In some of these the violence is absent; others are filled with scary war planes.

Nice and fairly chilling collection of defense ads. Relating them to the 19th Century sublime and proposing a perspectival tilt from terror to Godlike control is an ambitious thesis I’m not sure is proven here. The Constable clouds from the early 1800s are also seen from above. And you can find Church and Bierstadt examples where the perspective is from down below. it shouldn’t surprise us that ads for air force defense contractors prominently feature skies. In some of these the violence is absent; others are filled with scary war planes.

If this were a new thesis that MH was introducing first here, Tom Moody might be right to say the point hasn’t quite been proven yet, and it suffers from selective examples or a confirmation bias. But MH’s essay is drawing on Albert Boime’s already widely-regarded thesis, as well as maybe Angela Davis and other Art-Historians whose contemporary thesis-es on those schools of 19th c art are crucial and extensive. There are others (maybe Svetlana Alpers) whose writing about Aerial and Low-Vantage points in Dutch landscape that draw on similar connections about divine “providence” with then-emerging-bourgeois-entrepreneurship in a historical-context.

Having read Rosler’s recent image-essay, I see no reason why we shouldn’t see MH’s treatment of romantic propaganda as a valid expose on a certain aesthetic regime. It’s not about the form alone, it’s about cutting through the ether.

Very good to see this, been thinking about MH’s sublime-corp in aesthetic transition between the “empire” and “neo-naturalist” style of visual culture (Top Gun, Hunting-lodges) in the Bush years and whatever is emerging now- reticent pastoralism vs. mass-ornament perhaps.

If this were a new thesis that MH was introducing first here, Tom Moody might be right to say the point hasn’t quite been proven yet, and it suffers from selective examples or a confirmation bias. But MH’s essay is drawing on Albert Boime’s already widely-regarded thesis, as well as maybe Angela Davis and other Art-Historians whose contemporary thesis-es on those schools of 19th c art are crucial and extensive. There are others (maybe Svetlana Alpers) whose writing about Aerial and Low-Vantage points in Dutch landscape that draw on similar connections about divine “providence” with then-emerging-bourgeois-entrepreneurship in a historical-context.

Having read Rosler’s recent image-essay, I see no reason why we shouldn’t see MH’s treatment of romantic propaganda as a valid expose on a certain aesthetic regime. It’s not about the form alone, it’s about cutting through the ether.

Very good to see this, been thinking about MH’s sublime-corp in aesthetic transition between the “empire” and “neo-naturalist” style of visual culture (Top Gun, Hunting-lodges) in the Bush years and whatever is emerging now- reticent pastoralism vs. mass-ornament perhaps.

Excellent and thought provoking essay

Excellent and thought provoking essay

Comments on this entry are closed.