[Editor’s note: IMG MGMT is an annual image-based artist essay series. Today’s invited artist, Seth Price presents an essay challenging the traditional photo essay format. Born in 1973, the artist has widely exhibited internationally at Capitain Petzel Berlin, the Kunsthalle Zurich, Institute of Contemporary Arts London, Friedrich Petzel New York, Reena Spaulings Fine Art, and the Whitney Biennial. Price lives and works in New York City.]

1. Ritualized Unknowing

People keep trying to get a handle on what’s happening. There’s a fear that others are hastening to make startling connections among the raw material, tracing lines between points we didn’t even know existed. Exacerbating this anxiety is the fact that despite its supposed insistence on the consolidation of knowledge and the worth of information, the Internet produces ritualized unknowing. You could say, however, that this is a good thing, for it provokes a desire to remystify the frenzy of technological change through ritual, through a personal and allegorical rehearsal of what is perceived to be a manic and distorting increase in density, a compression exponentially telescoping in reach and magnitude.

To tame this frenzy we are offered the calming linearity of lists. While the persistence of the list as a constraint on the Internet’s data-cloud may simply be due to the persistence of small rectangular monitors, the list is clearly one of the chief organizational principles of the Internet. Search engines return lists; news is funneled into aggregations of that which is most flagged or emailed; blogs garnish their teetering stacks with the latest entries; a web page itself typically extends downward in a scrolling, implied list.

2. Hoardings

In recent years, some people have adopted the list form only to strip it to its foundation, yielding ultra-simple pages consisting of sequences of images cobbled together with little or no explanation, each image radically different from its neighbors, each likely to confound, amuse, or disquiet. These web pages are often “personal” pages belonging to artists or groups of artists. Text is relegated to minimal captions in these Internet wunderkammern, and sometimes abolished entirely.

Let’s call such a page a hoarding. The word can refer to a stash of collected goods, but can also mean a billboard, or the temporary wall thrown up around a construction site. The look of the hoarding is similar to that of a particular type of artist’s book that has flourished in the last 15 years or so, featuring page after page of heterogeneous images, a jumble of magazine scans, amateur snapshots, downloaded jpegs, swipes from pop culture and art history alike, some small, some full-bleed, none with explication. The similarity is not coincidental, for “the last 15 years or so” defines the Internet age as we know it, with its ubiquitous, colorful mosaics, evidently a powerful influence on publishing of all kinds.

What can we say about the experience of scrolling through a hoarding, trying to understand the procession of pictures? As in traditional fashion magazines, we find excitement and confusion in equal measure, with one catalyzing the other. Beyond that, it often seems that any information or knowledge in these pages is glimpsed only through a slight fog of uncertainty. Has an image been spirited out of the military defense community, or is it journalism; is it medical imaging, or pornography; an optical-illusion, or a graph; is it hilarious, disturbing, boring; is it doctored, tweaked, hue-saturated, multiplied, divided; is it a ghost or a vampire? In any event, the ultimate effect is: “What the fuck am I looking at?” Something that hovers in your peripheral vision.

One might ask, how does this depart from the queasily ambivalent celebration of the image that has characterized the last fifty years of pop culture, possibly the last century and a half of mass media? It could be the muteness of the offering, the lack of justification or context. But the observation that modern media divorce phenomena from context is a commonplace, and usually an invitation to reflect on the increasingly fragmented nature of experience. A hoarding is notable because while it is a public representation of a performed, elective identity, it is demonstrated through what appears to be blankness, or at least the generically blank frenzy of media.

This may be a response to the embarrassing and stupid demands of interactivity itself, which foists an infantilizing rationality on all “Internet art,” and possibly Internet use generally, by prioritizing the logic of the connection, thereby endorsing smooth functioning and well-greased transit. Recourse to the almost mystically inscrutable may be understood as a block to the common sensical insistence on the opposition of information to noise, and as a form of ritualized unknowing.

It could also be a dismissal of the ethos of self-consciously generous transparency that characterizes “web 2.0”: the freely offered opinions, the jokey self-effacement, the lapses into folksiness in the name of a desire to forge reasoned agreement and common experience among strangers. It is wise to mistrust this earnest ethos, which is inevitably accompanied by sudden and furious policing of breaches in supposedly normative behavior. This is not to argue that such consensus building is disingenuous, rather that it is simply politics, in the sense that politics is at heart concerned with separating out friends from enemies. In this view, the hard-fought equilibrium of an orderly on-line discussion is indistinguishable from its scourge, the flame war: reasonably or violently, both aim at resolution and a kind of confirmation of established precepts. Might a hoarding—a public billboard that declines to offer a coherent position, a temporary wall that blocks reasoned discourse—escape the duty to engage ratio and mores and resolution, in a kind of negative utopian critique? No, it probably cannot. But the perversity of its arrangement of pictures speaks for itself, and what it speaks of is manipulation.

Most design structures are short-lived, particularly on the Internet, and the “hoarding” will likely prove to be a breath in the wind. Can we say anything conclusive about the images, which themselves may indicate more lasting trends? Apart from their presentation, they often share an uncanny quality, a through-the-looking-glass oddity that stems from a predilection for digitally assisted composition, itself a synecdoche for manipulation. A given picture may have been generated by a graphics workstation, or it might be a found snapshot or news photograph subjected to alteration. Either way, what is proposed is a cybernetic vision, and a reflexive one: in gazing back at the emerging outline of a history of manipulation, it surveys its own slippery body, a snake coldly assessing the contours of recent meals. It has made a meal of news and sports and weather, of the military and medical establishments, of charts and diagrams, of jokes and games, of sex. It is interested in the abstraction and distortion of human expression and human form. The apotheosis of this tendency would be the computer-generated body, and, going further, computer-generated pornography.

So, is it computer-assisted perversity that is new about these images? Doubtful, though one could argue that the Internet makes it easy to circumvent traditional ethical standards since, should your current community sour on you, you can in effect join another, or start one from scratch. In a realm of numbers, it’s easy to form new islands at the leading edge of settlement. In such a realm it may not be possible to be crass, to step over the line, to incur that ignorant bit of finger wagging: “it’s a slippery slope.”

3. Teen Image

There are certain words, body-words like “fuck” and “shit” and “cunt” and “asshole,” which children and adults use freely, but hide from one another. The child knows the adult says it, and vice versa, but each pretends innocence around the other. Somewhere in the middle, however, the overlapping diagrams yield a portion of people who may say “fuck” with proper ownership of the term, who speak with the “devil-may-care” brio, panache, ésprit, élan, of the teenager.

A piece of computer-generated pornography is a teenage image. It is simultaneously ominous and absurd, empty and charged, futuristic and passé, and this uncanny indeterminacy disturbs nearly everyone, much the way a teenager standing in the street will discomfort both younger and older passersby. The teen image (the phrase is less awkward than “hoarding”, in fact suspiciously catchy) contains not only agreement and commonality but the antagonism and contradiction buried within common experience. It’s dumb, and it’s cunning. It skittishly glances both ways at once. It sees past and future alike. It’s like Janice’s face.

Speaking of pornography, why might it be that in this arena the genitals are usually shaven? A cock certainly appears longer when its nest of obscuring hair is freed from the base of the shaft, but this wouldn’t explain the frictionless cunt, the waxed asshole. It could be that such depilation comes out of a notion of cleanliness, of propriety even, an aversion to hair as a stand-in for dirt and disorder. This would be understandable in the sense that disorder is a mechanical irritant, and the removal of hair facilitates smooth functioning so that parts A and B may fuse with minimal resistance, speeding us toward our goal. This seems like a promising answer, in part because all pornography outside the printed page occurs in playback, and therefore can be understood as a time-based process inscribed within capital, technology, and all the rest; within the logic of the Internet, it’s one more successful link. If we could only do everything on-line!

On the other hand, a smooth asshole is a young asshole. Maybe in pornography the genital hair is removed because this slight deviance suggests the body of the child. However, while deviance is usually bluntly and reflexively reduced to sexual difference, and while our time and place considers sex with children to be among the “most different” and therefore proscribed behaviors, in this case the shaven genitals might refer not to some helpless morsel but to ones’ own, long-forgotten, pre-pubescent self. Another deviance altogether! To identify with that self is to confront an uncanny wraith, mostly due to the stubborn difficulty of recollection. Try to remember your distracted gaze downward, idly taking in the young self, the true self beyond mirrors or photos, a slippery body spied from headless central command, the smooth genitalia at the center. Not only is the picture hard to envision, but in attempting to do so you’re forced to imagine a naked child. Anxiety intrudes, at which point the ego asserts: “Not to worry, it’s supposed to be us! We hold the rights to this one.” This uneasy vacillation marks it as a teen image.

Computers have the opposite problem: they face significant challenges when asked to represent hair, wrinkles, dirt, slack wattles—in a word, aging. Irritatingly vigorous and robust, CGI is best suited to representing children, or, as in so many animated films today, adults as children. Whether shaven genitalia register a desire for childhood or simply an ambivalence about aging, it makes sense that CGI would be perfect for pornographic use.

So, can we say there is something special about a computer-generated rendering of a smoothly hairless child-adult having sex with another child-adult? (Child on adult? Child on child?) We can say this, yes, though with hesitation, and maybe sotto voce. But there is a clear relationship to popular images, even if it may not transcend the observation that we are intensely interested in images of sex and images of youth, and that in such a picture they overlap nicely. Maybe we should leave all this for others to resolve, merely noting in closing that while violence and domination are reprehensible, there’s nothing inherently wrong with finding children sexually arousing.

4. Frenzy

Art is sometimes taken to be a kind of seismograph that registers the effects of cultural change. In this view, art’s objects and gestures yield distanced reflection and insight: from the frenzy, a distillation. But the term ‘ritualized unknowing,’ used above in reference to the Internet, could also describe a response to the banal condition of trying to understand what’s happening that one finds in art discourse, which seeks to explain how art explains, to show how art shows, to suggest what art is trying to suggest.

There is a paradox in the very attempt to understand an unfamiliar art practice, which today is usually initiated through the medium of two-dimensional or screen-based images. Initially you grapple with a nebulous apparition in your mind’s eye, a suspicion that something hovers beyond with no name forthcoming, but this sense of looming energies and meaning often shrinks when you finally inspect the actual artworks, which reveal themselves to consist of mere objects or gestures, as do all artworks. No matter how powerful the work, you’re tempted to say: “But this is just…” Just an object, just a gesture. It would be a mistake, though, to think that your disillusionment upon scrutinizing the “actual” art is a bad thing. A gap has surely opened in your experience of the work, but art depends on this split between the fragile interiority of speculation and the more public and bodily activity of looking, which partakes of space. Your first impression, rare and valuable as it is, is only richer for the betrayal.

Frenzy might in fact be homeopathic, its anxiety-producing presence a spur, although rather than encourage the articulation of meaning, it encourages existing chains of associations to fold in a strange and unanticipated way, aligning incompatible ideas and holding them in awkward proximity. For example, a human body subjected to frenzies of processing is an aggressive and disturbing alienation, but the threat is also fascinating; like a gif-compressed headshot, a Cubist portrait recalls the ancient ritual gesture of donning a mask or hood, and the ambivalent pleasures of othering oneself. Fashion also hunts this path.

“We were trying to get to this place—it was me and you, I think, and some other people—and it was a little like my house ”¦ Although, well, it was my house, but it didn’t look like my house, somehow. And we were trying not to be seen.”

Why does this stumbling sentence so clearly represent a dream in the telling?

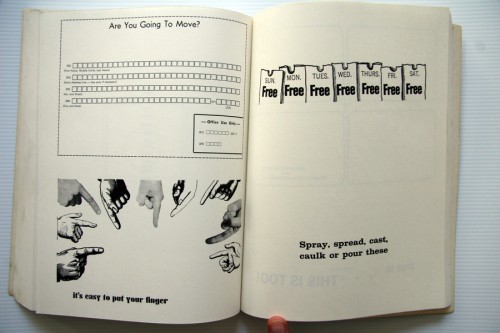

Bernd Porter’s “Found Poems” from 1972. Pieces of heterogeneous printed detritus, reassembled and presumably rephotographed in the printing process. It’s nice to think that these collages, which were probably laid out carefully, aided by facsimiles, white-out, and tape, existed alongside the book, rather than being subsumed or created through the process of publishing and distribution, as is often the case with internet ‘collage’. Computers conceal distance; their collage move consists of juxtaposing elements that might be stored hundreds or thousands of miles apart, giving an illusion of spatial continuity.

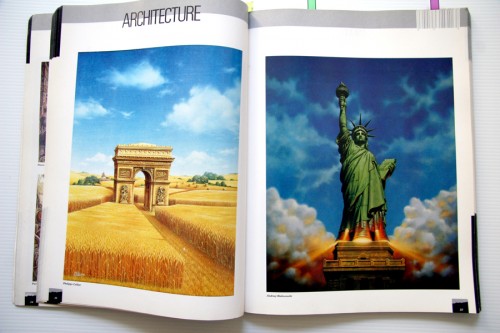

A commercial stock illustration book, “Art Stock,” from 1986. Most of the illustrations are quite small advertisements for what could be purchased in full size; for some reason the (French) publisher chose to highlight these two paintings. Often these kinds of stock illustrations are filled with symbolic meaning but kept purposely ambiguous so as to appeal to as broad a customer base as possible.

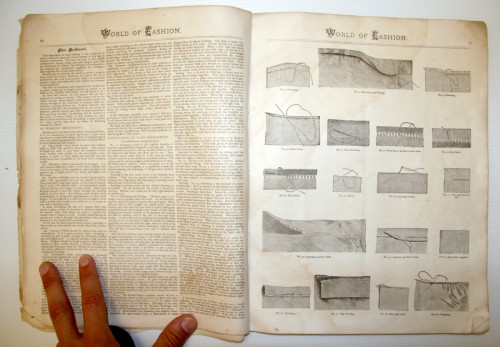

“World of Fashion”, February 1876. In general, the form of the fashion magazine as we know it is virtually unrecognizable here. First of all, illustrations of any kind were scarce. This was a point relatively early in the growth of the magazine as a popular form; photos were not yet used by this sort of publication, and presumably lithographs were expensive and time consuming. This page, one of the few full page illustrations in the magazine, shows the kind of thing women looked to a fashion magazine to provide: an array of stitches and hemlines, to be reproduced at home.

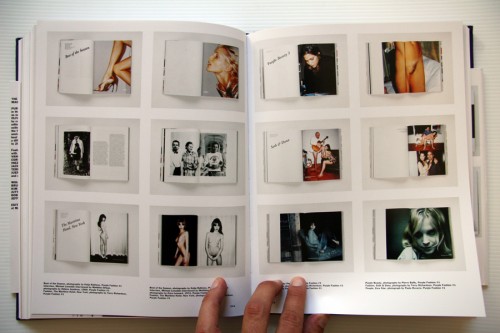

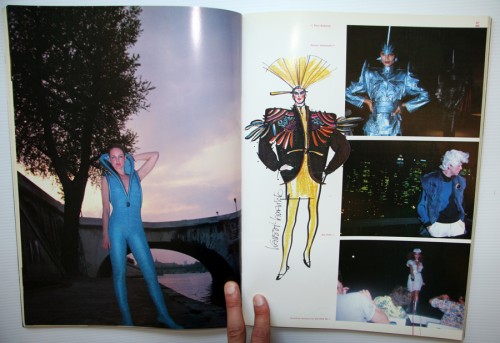

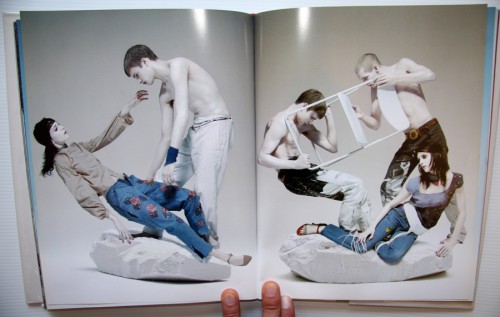

Something increasingly popular in the last few years: the representation of books through dispassionately photographed spreads, often with the surface on which they rest peeking around the edges. An almost clinical approach to a historical overview, one used by this feature itself. A little precious, maybe, but a natural reaction to what has happened to images in the last 15 years: a conscious choice not to use scanners and a striving to represent the book as object, rather than one more brief stop for images on their way from one place to another. It does make it hard to read the text and enjoy the pictures, which is an interesting wrinkle, until it gets over-used. This is from “The Purple Anthology,” 2008.

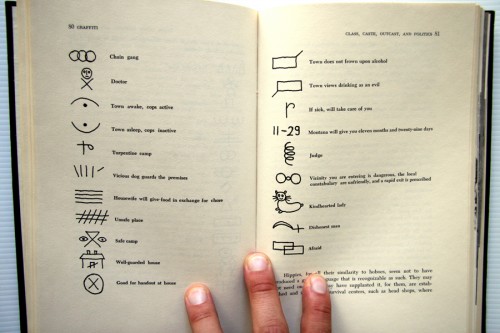

“Hobo Codes” supposedly inscribed in public places as coded messages to like-minded passersby: “Well-guarded house”, “Dishonest man”. Recently these were used in AMC’s TV show Mad Men, maybe to make an ambiguous point about how the power of signs and symbols was revealed to a future advertising executive. From “Graffiti”, Reisner, 1971.

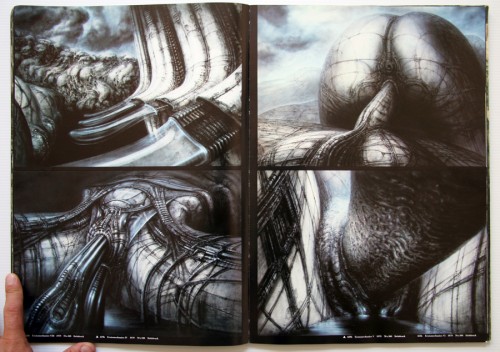

Giger. The “father” of biomorphic illustration and set design, most famously for Ridley Scott’s Alien, though also for various album covers and a series of art based on the Swatch watch. Obsessed with an eroticism tied to distortion. His images are as much about entropy and decay as they are about sex or futurism: the mortification of the flesh and the breakdown of the machine are equally important. From “Necronomicon 2”, 1985.

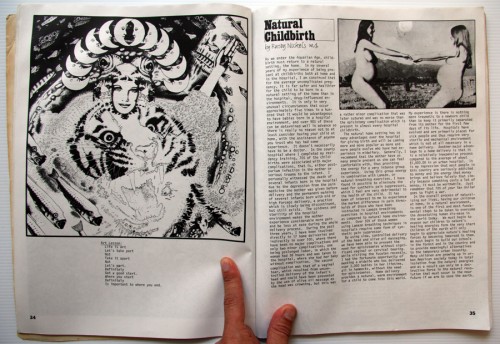

Aquarian age. Characteristic illustration style of the time: dense organic patterning and baroque decoration rendered in a humble line, a spidery hand; homespun naïvete or faux-naïvete; the suggestion of a synthesis of nature and human. This one accompanies a feature on Natural Childbirth, from “Aquarian Angel”, 1972.

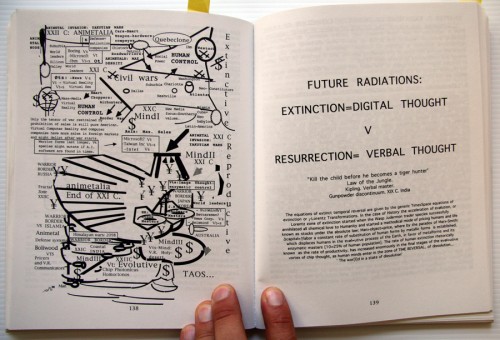

Example of an illustration that obscures rather than illuminates the text. This diagram from a self-published book called “Radiations: The Extinctions of Man,” which I found at a church sale. Musings on technology, art, and human existence, all in impenetrable language. As far as I could tell there was no author named anywhere in the book. Probably early 90s, judging from MacPaint patterns used elsewhere in the book.

Nearly 30 years old, this book imagines fashion of the future. White pompadour wigs never did spread among men, although that guy looks pretty good. It is fashion illustration that has apparently not changed much: the amazingly tapered, spindly legs, legs purely as risers, display stands for the billboard of the torso. From “Fashion 2001,” by Lucille Khornak, 1982.

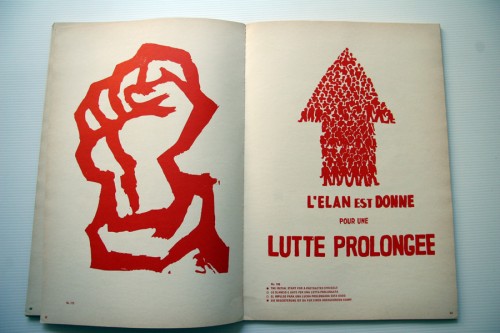

Atelier Populaire posters, 1968. Archetypal images of protest, here stamped with the hardcore pedigree of les soixante-huitards. The raised fist, an arrow upwards, a symbol comprised of people… The English translation doesn’t seem very punchy, but maybe more interesting for that: “the initial start for a protracted struggle”. “Élan” would have done fine in English too, but maybe would have trivialized the message (too close to Esprit?). From “Atelier Populaire”, 1969.

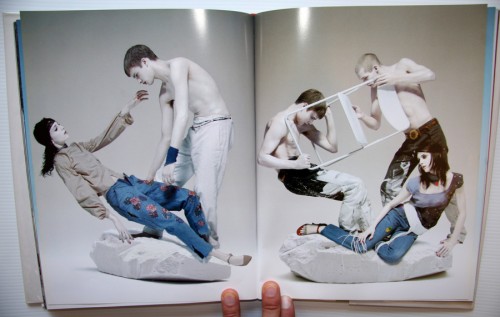

Fashion took to digital montage and augmentation early. This example is relatively subtle. From “The Impossible Image: Fashion Photography in the Digital Age,” 2000.

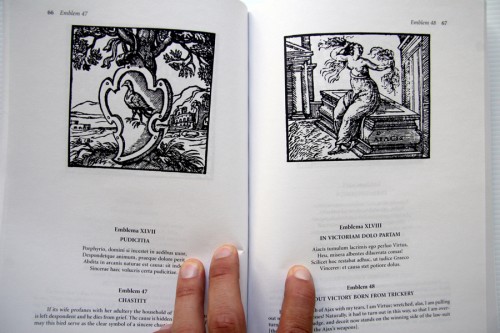

Reproductions from a reprinting of Andrea Alciati’s Emblematum liber, 1531. Emblem Books were popular compendia featuring page after page of epigrammatic texts, normally with illustrations. A reader coaxed meaning out of the combination of picture and text. Sometimes it seems as if the text was generated to explain the picture, and with others it’s the reverse. One notorious emblem remained long unillustrated, for it described the act of literally shitting where one eats: “This act stands for all offenses exceeding the canonic measure of sacred law”¦”

{ 76 comments }

Hi, Seth. It seems you are more interested in books than the Net. Many of your references to the Net are negative or written in a dry, anthropological tone. (“Self-consciously generous transparency,” “an infantilizing rationality,” “circumvent[ing] traditional ethical standards,” and so on.) You sound at times like a threatened print writer criticizing bloggers. Your collection is also a disconnected hoard of images but the subject matter is books and magazines. Is having the fingers in each shot to distance yourself, as the antiquarian lover of one type of medium, from the complained-about effects of the medium in which you are communicating? The idea of showing books as a retro “hoard” page is great but could probably do without the accompanying talking down to Internet users. Books and magazines have their limitations and pathologies as well. (Maybe that’s the point you’re making–if so it could be clearer.)

Hi, Seth. It seems you are more interested in books than the Net. Many of your references to the Net are negative or written in a dry, anthropological tone. (“Self-consciously generous transparency,” “an infantilizing rationality,” “circumvent[ing] traditional ethical standards,” and so on.) You sound at times like a threatened print writer criticizing bloggers. Your collection is also a disconnected hoard of images but the subject matter is books and magazines. Is having the fingers in each shot to distance yourself, as the antiquarian lover of one type of medium, from the complained-about effects of the medium in which you are communicating? The idea of showing books as a retro “hoard” page is great but could probably do without the accompanying talking down to Internet users. Books and magazines have their limitations and pathologies as well. (Maybe that’s the point you’re making–if so it could be clearer.)

yes seth please make your points clearer! I’m on the internet all the time and have a hard time thinking when i read. also don’t be so mean to the internet–it is very sensitive about its cultural status. so…uh…..yeah.

yes seth please make your points clearer! I’m on the internet all the time and have a hard time thinking when i read. also don’t be so mean to the internet–it is very sensitive about its cultural status. so…uh…..yeah.

The tone of both these comments needs to be moderated. I don’t want to see a flame war here.

The tone of both these comments needs to be moderated. I don’t want to see a flame war here.

I liked

1.the intersection betwen vertical lists and nebulous, rhizomatic “nets” (reproduced in the list-like, cumulative grumblings from the low, moody, art-fag city)

2.analysis of the treatment of aging, or lack of it, in digital media/CGI/internet porn

3. the fusion of the two (“connectivity”) in the idea of infantilized, well-greased transit as both logic and image in teen images

I liked

1.the intersection betwen vertical lists and nebulous, rhizomatic “nets” (reproduced in the list-like, cumulative grumblings from the low, moody, art-fag city)

2.analysis of the treatment of aging, or lack of it, in digital media/CGI/internet porn

3. the fusion of the two (“connectivity”) in the idea of infantilized, well-greased transit as both logic and image in teen images

Still mystified by the connection between the (non-teen) book images and the “analysis of the treatment of aging, or lack of it, in digital media/CGI/internet porn.” I realize I should be drawing the connections myself, so here goes: “Books introduced many of the templates we see on the current Net, but unlike the Net with its emphasis on shaven newness, books get cooler the older they are.”

Still mystified by the connection between the (non-teen) book images and the “analysis of the treatment of aging, or lack of it, in digital media/CGI/internet porn.” I realize I should be drawing the connections myself, so here goes: “Books introduced many of the templates we see on the current Net, but unlike the Net with its emphasis on shaven newness, books get cooler the older they are.”

After reading through this, the giggle I had at the first three comments was just what I needed to clense the palate.

A lot of great stuff in this article. Some annoyances, sure, but such is the way of arts writing. Opinionated people are worth reading.

After reading through this, the giggle I had at the first three comments was just what I needed to clense the palate.

A lot of great stuff in this article. Some annoyances, sure, but such is the way of arts writing. Opinionated people are worth reading.

In my reading the focus of this essay is not the Internet. The Internet offers a unique opportunity to perceive a global cultural trend or tendency, and list-making and what Seth calls “hoarding” are tendencies I’ve observed, too. I just had never taken the time to reflect on them specifically. I would not have thought to include a discussion of prepubescent eroticism or shaved genitalia, I do find the connection or line resonant and will now ponder why. Must be a reason. There’s mystery here, and an intended or unintended refusal to be coherent or finite, which was what I took to be the point. What I liked most was Seth’s comment about the art world’s “painted in the corner” self-reflexivity on its own cultural status.

In my reading the focus of this essay is not the Internet. The Internet offers a unique opportunity to perceive a global cultural trend or tendency, and list-making and what Seth calls “hoarding” are tendencies I’ve observed, too. I just had never taken the time to reflect on them specifically. I would not have thought to include a discussion of prepubescent eroticism or shaved genitalia, I do find the connection or line resonant and will now ponder why. Must be a reason. There’s mystery here, and an intended or unintended refusal to be coherent or finite, which was what I took to be the point. What I liked most was Seth’s comment about the art world’s “painted in the corner” self-reflexivity on its own cultural status.

“After reading through this, the giggle I had at the first three comments was just what I needed to clense the palate.”

I agree.

Good points made. I also find the somewhat omission of the author’s own stance on each area he explores refreshing.

“After reading through this, the giggle I had at the first three comments was just what I needed to clense the palate.”

I agree.

Good points made. I also find the somewhat omission of the author’s own stance on each area he explores refreshing.

So which is it, opinionated or stanceless? (Rest assured that if this flame war gets any worse for me I will move on to another blogger’s comments.)

So which is it, opinionated or stanceless? (Rest assured that if this flame war gets any worse for me I will move on to another blogger’s comments.)

perhaps this “muteness of the offering” is another doomed attempt at a tactical defensive delay that plays the same game it decries

perhaps this “muteness of the offering” is another doomed attempt at a tactical defensive delay that plays the same game it decries

I don’t think that Seth Price disrespects the internet. Far from it. To me, he seems totally in awe. And certainly, he’s not talking down to bloggers. If so why would he waste the efforts of such a magisterial piece that is just as much historical analysis of the image as it is work of art. For sure, Price brings together such a diverse collection of thoughts and images that it made me dizzy. But that’s the point. In the digitalized space of the internet, size and distance offer no bearing and any number of connections or interpretations can be made. The internet is a realm of non linear series or lists where intensities are arranged by ordinal numbers without metric specificity. As such, there are no clear points leading to fixed predetermined identities. At the same time he suggests that its homogeneous structure with the seeming power to resolve all differences can easily serve totalitarian ends. As a counter, through reflection and humor, he folds the internet back on itself. In so doing he shows that without the contrast space of book spines, pubic hair or fingers we’ll get stuck in a regime that does not allow for anything new, a regime in which we’re forced to eat where we shit.

I don’t think that Seth Price disrespects the internet. Far from it. To me, he seems totally in awe. And certainly, he’s not talking down to bloggers. If so why would he waste the efforts of such a magisterial piece that is just as much historical analysis of the image as it is work of art. For sure, Price brings together such a diverse collection of thoughts and images that it made me dizzy. But that’s the point. In the digitalized space of the internet, size and distance offer no bearing and any number of connections or interpretations can be made. The internet is a realm of non linear series or lists where intensities are arranged by ordinal numbers without metric specificity. As such, there are no clear points leading to fixed predetermined identities. At the same time he suggests that its homogeneous structure with the seeming power to resolve all differences can easily serve totalitarian ends. As a counter, through reflection and humor, he folds the internet back on itself. In so doing he shows that without the contrast space of book spines, pubic hair or fingers we’ll get stuck in a regime that does not allow for anything new, a regime in which we’re forced to eat where we shit.

“perhaps this “muteness of the offering†is another doomed attempt at a tactical defensive delay that plays the same game it decries.”

So true. So true. But I might add, “perhaps it isn’t.”

I thought that the main point of Mr. Price’s piece was that through the very act of reading, we all become pedophiles.

[Editor’s note: This comment has been edited]

“perhaps this “muteness of the offering†is another doomed attempt at a tactical defensive delay that plays the same game it decries.”

So true. So true. But I might add, “perhaps it isn’t.”

I thought that the main point of Mr. Price’s piece was that through the very act of reading, we all become pedophiles.

[Editor’s note: This comment has been edited]

I’m not sold on the word “Hoarding” as the ideal descriptor for the phenomenon outlined in the essay. To me, hoarding connotes a selfish form of collecting-taking something away from others to be enjoyed in exclusivity. The internet image banks/collections reflect a generosity of spirit since they are free and for all to access. I think a more neutral descriptor would be better. Any suggestions out there?

I’m not sold on the word “Hoarding” as the ideal descriptor for the phenomenon outlined in the essay. To me, hoarding connotes a selfish form of collecting-taking something away from others to be enjoyed in exclusivity. The internet image banks/collections reflect a generosity of spirit since they are free and for all to access. I think a more neutral descriptor would be better. Any suggestions out there?

Thanks, Andy, that ties things together nicely. Alex Galloway has written, from the new media side, about the seamlessness of the web and attempts to disrupt it through messing with its technical and linguistic protocols. (Some artists are for it, others against.) The books for me add a dimension of time as well as “contrast space.” Internet controversies are measured in seconds but seeing the “fashion magazine” brings home the kind of slow shifts in the culture that would have to occur to make the stitching seem utterly alien today (while invoking a poignant sense of all the knowledge and handcraft that is lost). The books show rather than tell which is why I mostly appreciate the photo essay part of this.

Thanks, Andy, that ties things together nicely. Alex Galloway has written, from the new media side, about the seamlessness of the web and attempts to disrupt it through messing with its technical and linguistic protocols. (Some artists are for it, others against.) The books for me add a dimension of time as well as “contrast space.” Internet controversies are measured in seconds but seeing the “fashion magazine” brings home the kind of slow shifts in the culture that would have to occur to make the stitching seem utterly alien today (while invoking a poignant sense of all the knowledge and handcraft that is lost). The books show rather than tell which is why I mostly appreciate the photo essay part of this.

I agree w/Saul, that “hoarding” suggests some kind of abject private accumulation, usually compulsively acquired and shamefully hidden by their singular collector. Oprah has dedicated entire shows to the exploitation and “curing” of “hoarders,” and the kind of bewildering pictorial taxonomies that Seth is referring to sound more like the act of a bricoler. And even if the posted images are wildly dissimilar, they’re still stacked and organized within the scrollable webpage, so a very specific order always underpins and standardizes the superficially-dissonant affair. Sharing and accessibility are also ingrained in this structure, so they’re also like public libraries, however wild their content. So, maybe bricoler-librarians, independent curators?

I agree w/Saul, that “hoarding” suggests some kind of abject private accumulation, usually compulsively acquired and shamefully hidden by their singular collector. Oprah has dedicated entire shows to the exploitation and “curing” of “hoarders,” and the kind of bewildering pictorial taxonomies that Seth is referring to sound more like the act of a bricoler. And even if the posted images are wildly dissimilar, they’re still stacked and organized within the scrollable webpage, so a very specific order always underpins and standardizes the superficially-dissonant affair. Sharing and accessibility are also ingrained in this structure, so they’re also like public libraries, however wild their content. So, maybe bricoler-librarians, independent curators?

Regarding Saul’s comment on the issue of nomenclature and ‘hoarding’: I think networked culture in a wider sense (the Internet included of course) remains a place of discoveries rather than gifts. To describe the exchanges that take place there, then, as partaking in a regime of spirited generosity seems to me a misreading of how we acquire or share information in those places. More and more the shift on the web at least seems to be away from Tim Berners-Lee’s model of users following a pathway of referring sites intuitively or deliberately hyperlinked by content creators, and instead to a search model, where infromation is meted out in response to particular requests and their (sometimes tempramental) algorithmic decodings. We always get what we ask for online, but perhaps not what we expect.

I think Seth Price’s reading of the teen image in visual culture touches in a subtle but not unimportant way on the the issue of time: a prime engine for the production of meaning in both networked computing and Seth’s own work as an artist. Data accrues online only over time of course, but more importantly: what we in fact “share” or “hoard” online is without question a marker of a time passed, keyed or moused into our terminals. The fabrication of a fictional time is possible (dynamic content), but remains infinitely supplicant to that which we daily loan out without interest or hope for return.

Regarding Saul’s comment on the issue of nomenclature and ‘hoarding’: I think networked culture in a wider sense (the Internet included of course) remains a place of discoveries rather than gifts. To describe the exchanges that take place there, then, as partaking in a regime of spirited generosity seems to me a misreading of how we acquire or share information in those places. More and more the shift on the web at least seems to be away from Tim Berners-Lee’s model of users following a pathway of referring sites intuitively or deliberately hyperlinked by content creators, and instead to a search model, where infromation is meted out in response to particular requests and their (sometimes tempramental) algorithmic decodings. We always get what we ask for online, but perhaps not what we expect.

I think Seth Price’s reading of the teen image in visual culture touches in a subtle but not unimportant way on the the issue of time: a prime engine for the production of meaning in both networked computing and Seth’s own work as an artist. Data accrues online only over time of course, but more importantly: what we in fact “share” or “hoard” online is without question a marker of a time passed, keyed or moused into our terminals. The fabrication of a fictional time is possible (dynamic content), but remains infinitely supplicant to that which we daily loan out without interest or hope for return.

As I understand this comment “spirited generosity” isn’t an entirely accurate way to describe exchange on the internet et al because users rarely “stumble upon” information. So the rationale here is that seeking material out is different then being given a link, and therefore not quite as generous as the rhetoric of the web would have us believe?

If I’m reading this correctly, I’d generally agree, though I rather enjoy that the web holds on to this kind of idealistic lexicon, (except of course when it’s co-opted as a commercial operative.) With that said, as one example, I don’t think a search function even exists on facebook’s newsfeed, so Saul’s comment isn’t necessarily a misreading of the way in which we exchange information.

As I understand this comment “spirited generosity” isn’t an entirely accurate way to describe exchange on the internet et al because users rarely “stumble upon” information. So the rationale here is that seeking material out is different then being given a link, and therefore not quite as generous as the rhetoric of the web would have us believe?

If I’m reading this correctly, I’d generally agree, though I rather enjoy that the web holds on to this kind of idealistic lexicon, (except of course when it’s co-opted as a commercial operative.) With that said, as one example, I don’t think a search function even exists on facebook’s newsfeed, so Saul’s comment isn’t necessarily a misreading of the way in which we exchange information.

I don’t think the Berners-Lee vision is dead or dying. A few years ago you had to identify a permalink for something you wanted to save or share. Now there’s a staggering array of “share services” (Digg, twitter, Mixx, linkedin) for every bit of content on the Web. Presumably someone is using these. As for “Seth Price’s reading of the teen image,” and “Seth’s own work as an artist,” Bosko, I don’t think we’re anywhere near having a consensus on what either of those things are. What does a book that Price found at a church sale, for example, have to do with the “teen image”? I’d be curious to know how we get from “Price collected all these books” to “Seth Price’s reading of the teen image in visual culture.” Andy Stillpass’s after-the-fact reading of the essay is pretty good–do you agree with it?

I don’t think the Berners-Lee vision is dead or dying. A few years ago you had to identify a permalink for something you wanted to save or share. Now there’s a staggering array of “share services” (Digg, twitter, Mixx, linkedin) for every bit of content on the Web. Presumably someone is using these. As for “Seth Price’s reading of the teen image,” and “Seth’s own work as an artist,” Bosko, I don’t think we’re anywhere near having a consensus on what either of those things are. What does a book that Price found at a church sale, for example, have to do with the “teen image”? I’d be curious to know how we get from “Price collected all these books” to “Seth Price’s reading of the teen image in visual culture.” Andy Stillpass’s after-the-fact reading of the essay is pretty good–do you agree with it?

The books I wouldn’t read in a literal way, either formally or being the thing that they are: books. Instead, I think it’s much more interesting to think of them as a collection. They were found and collected, not all at once, one would assume, but over time…

The books I wouldn’t read in a literal way, either formally or being the thing that they are: books. Instead, I think it’s much more interesting to think of them as a collection. They were found and collected, not all at once, one would assume, but over time…

Right, but why is the teen image a metaphor for that? Sounds more like Grandpa and his collection of paperbacks. People are cutting Price a lot of slack here. Andy says it’s because “teens = new” and the collection is a slight corrosion of that newness, somehow. To read it that way you have to ignore the actual content of the collection, as you are doing. The opposite of literal-minded is uncritical.

Right, but why is the teen image a metaphor for that? Sounds more like Grandpa and his collection of paperbacks. People are cutting Price a lot of slack here. Andy says it’s because “teens = new” and the collection is a slight corrosion of that newness, somehow. To read it that way you have to ignore the actual content of the collection, as you are doing. The opposite of literal-minded is uncritical.

Ok.

Please help me.

1. Who is Janice?

2. Granted, the mise en abyme of the book spread is current(ly), an epidemic.

A. How is the image of a book spread in

a book spread

different from

B. Xerox of a book spread

different from

C. a page scanned and a printed in a book (cp, ddd, etc)

different from

D. a text which is retyped and printed in a book.

different from

a. (A) on the internet, disc, pda, or data space

b. (B) on the internet, disc, pda, or data space

c. (C) on the internet, disc, pda, or data space

d. (D) on the internet, disc, pda, or data space

3. If “the persistence of the list†is perhaps “due to the persistence of small rectangular monitors,†is it useful for us to hallucinate another option? Does the “data-cloud†spread out, or deep, or how?

4. [related to 3.] As “computers conceal distance,†how to diagram that distance, give visibility to the true shape of that “data-cloud�

5. Is the hair like a slow connection? Full beaver as dial up? And the hopes of an impossibly instant modem the projected equal of instant satisfaction? Desire with zero resistance.?.

6. Ekprhasis of these hoards seems increasingly unlikely. Too many tendrils from too many peripherals for description to keep up with. Isn’t this good, this undescribable? {which the author demonstrates above is not the same as the unexplainable}

And maybe this will help someone else.

1. The teen image certainly is in fact suspiciously catchy.

2. Stillpass is one of the best of his trade.

3. We fell for it.

Ok.

Please help me.

1. Who is Janice?

2. Granted, the mise en abyme of the book spread is current(ly), an epidemic.

A. How is the image of a book spread in

a book spread

different from

B. Xerox of a book spread

different from

C. a page scanned and a printed in a book (cp, ddd, etc)

different from

D. a text which is retyped and printed in a book.

different from

a. (A) on the internet, disc, pda, or data space

b. (B) on the internet, disc, pda, or data space

c. (C) on the internet, disc, pda, or data space

d. (D) on the internet, disc, pda, or data space

3. If “the persistence of the list†is perhaps “due to the persistence of small rectangular monitors,†is it useful for us to hallucinate another option? Does the “data-cloud†spread out, or deep, or how?

4. [related to 3.] As “computers conceal distance,†how to diagram that distance, give visibility to the true shape of that “data-cloud�

5. Is the hair like a slow connection? Full beaver as dial up? And the hopes of an impossibly instant modem the projected equal of instant satisfaction? Desire with zero resistance.?.

6. Ekprhasis of these hoards seems increasingly unlikely. Too many tendrils from too many peripherals for description to keep up with. Isn’t this good, this undescribable? {which the author demonstrates above is not the same as the unexplainable}

And maybe this will help someone else.

1. The teen image certainly is in fact suspiciously catchy.

2. Stillpass is one of the best of his trade.

3. We fell for it.

“I rather enjoy that the web holds on to this kind of idealistic lexicon, (except of course when it’s co-opted as a commercial operative.)”

But isn’t the idealistic lexicon that “the web” holds on to (hoards?) complicit with a kind of cleansing operation? Generosity, sharing, the gift economy etc. are to be supported as long as it is clear that one, at some level, knows better and it’s done within the realm of consensus that will be enforced if necessary through moderating comment boards and so forth. Sure spirited debate is fine as long as everyone remains civil and respectful, calls each other by their first names and equates criticality with literal-mindedness. And yes, of course, commerce is bad, but somehow provocation is appreciated only if it is attached to a name that has capital in the art world.

“I rather enjoy that the web holds on to this kind of idealistic lexicon, (except of course when it’s co-opted as a commercial operative.)”

But isn’t the idealistic lexicon that “the web” holds on to (hoards?) complicit with a kind of cleansing operation? Generosity, sharing, the gift economy etc. are to be supported as long as it is clear that one, at some level, knows better and it’s done within the realm of consensus that will be enforced if necessary through moderating comment boards and so forth. Sure spirited debate is fine as long as everyone remains civil and respectful, calls each other by their first names and equates criticality with literal-mindedness. And yes, of course, commerce is bad, but somehow provocation is appreciated only if it is attached to a name that has capital in the art world.

If you want to think that the removal of name calling has something to do with literal mindedness, how big you are in the art world, and my own ego that’s fine, but has no basis in reality.

Tom Moody doesn’t think commentors are being very critical. He might have put it nicer, but he’s allowed to say that.

If you want to think that the removal of name calling has something to do with literal mindedness, how big you are in the art world, and my own ego that’s fine, but has no basis in reality.

Tom Moody doesn’t think commentors are being very critical. He might have put it nicer, but he’s allowed to say that.

AFC, I was not accusing you of anything, but rather posing a genuine question that is a response to the piece above.

Quoting Price:

“It is wise to mistrust this earnest ethos, which is inevitably accompanied by sudden and furious policing of breaches in supposedly normative behavior. This is not to argue that such consensus building is disingenuous, rather that it is simply politics, in the sense that politics is at heart concerned with separating out friends from enemies. In this view, the hard-fought equilibrium of an orderly on-line discussion is indistinguishable from its scourge, the flame war: reasonably or violently, both aim at resolution and a kind of confirmation of established precepts.”

The “name-calling” that you edited out above was in the same spirit. I don’t know the person in question or anything about him. I understand why you did it. Not because of your ego but because of protocol. You did it because I was being a “troll.” And if you want to maintain a respectable website, you moderate trolls. My question is why is good, critical debate allowed and “trolling” not allowed? Or more pointedly, why is the idealism about the internet that you endorse always coupled with moderation?

AFC, I was not accusing you of anything, but rather posing a genuine question that is a response to the piece above.

Quoting Price:

“It is wise to mistrust this earnest ethos, which is inevitably accompanied by sudden and furious policing of breaches in supposedly normative behavior. This is not to argue that such consensus building is disingenuous, rather that it is simply politics, in the sense that politics is at heart concerned with separating out friends from enemies. In this view, the hard-fought equilibrium of an orderly on-line discussion is indistinguishable from its scourge, the flame war: reasonably or violently, both aim at resolution and a kind of confirmation of established precepts.”

The “name-calling” that you edited out above was in the same spirit. I don’t know the person in question or anything about him. I understand why you did it. Not because of your ego but because of protocol. You did it because I was being a “troll.” And if you want to maintain a respectable website, you moderate trolls. My question is why is good, critical debate allowed and “trolling” not allowed? Or more pointedly, why is the idealism about the internet that you endorse always coupled with moderation?

Roscoe, I don’t think editing name-calling (or asking that it not be done) is necessarily about “maintaining a respectable website.” Bloggers are human and these forums are completely voluntary (“generous” to use the idealistic word). Some mornings you just don’t want to wake up, look at your page, and see strangers saying to other, “Oh, yeah, well, what about this, asshole?” There’s idealism and then there’s letting people use you.

Roscoe, I don’t think editing name-calling (or asking that it not be done) is necessarily about “maintaining a respectable website.” Bloggers are human and these forums are completely voluntary (“generous” to use the idealistic word). Some mornings you just don’t want to wake up, look at your page, and see strangers saying to other, “Oh, yeah, well, what about this, asshole?” There’s idealism and then there’s letting people use you.

And I have no desire for this website or anyone else to censor Tom Moody. Indeed, I want more Tom Moody. I just pointed out that he equated criticality with literal-mindedness, which I think is very interesting.

And I have no desire for this website or anyone else to censor Tom Moody. Indeed, I want more Tom Moody. I just pointed out that he equated criticality with literal-mindedness, which I think is very interesting.

Tom, that’s interesting. You think it’s less about public display (idealism) and more about keeping house (lifestyle). It’s “your” page and you “generously” offer it to others but you have the final word.

Tom, that’s interesting. You think it’s less about public display (idealism) and more about keeping house (lifestyle). It’s “your” page and you “generously” offer it to others but you have the final word.

Oh Jesus. Comments like this are why sites with larger resources hire someone to moderate. Speaking of which, since we’re only barely discussing the Price piece at this point, I’m calling the last word and closing the comments. Think what you will.

Oh Jesus. Comments like this are why sites with larger resources hire someone to moderate. Speaking of which, since we’re only barely discussing the Price piece at this point, I’m calling the last word and closing the comments. Think what you will.

I just want to help with the term hoarding as it there another sense of the word, and I think it is more in line with the way the Seth uses it.

A hoarding is the temporary wall that is built around a construction site. Often, these are covered in posters and advertising material. The hoarding, online and in physical space is the visual overload that can be found in common spaces.

The idea of common spaces is interesting because the common is something that is not strictly public, but is shared.

I just want to help with the term hoarding as it there another sense of the word, and I think it is more in line with the way the Seth uses it.

A hoarding is the temporary wall that is built around a construction site. Often, these are covered in posters and advertising material. The hoarding, online and in physical space is the visual overload that can be found in common spaces.

The idea of common spaces is interesting because the common is something that is not strictly public, but is shared.

To jump in to this already exciting debate, I would like to speak in favor of both parties and try to point out what I think Price might be getting at. After a couple of reads, although he stumbles around with metaphors, I understand it to be an examination of the characteristics of the medium of digital art. I’ve broken his post down into a list(!).

1. It seems to me that the main debate here is over the connections between the images and sections of the essay composed by Price, and that any source of conflict over the work is derived from various readers “hastening to make startling connections among the raw material, tracing lines between points we didn’t even know existed.” This is ironic, and it seems that he’s pointing out the tendency that internet communication lends to discussions of topics. What really frustrates me is that we never seem to receive a decent explanation of what exactly “ritualized unknowing” is, particularly in context.

2. “To tame this frenzy we are offered the calming linearity of lists.” This essay is a list. The topics are not literally connected, rather Price has tamed (or at least made linear) his thought-web for our viewing. Is this a postmodern exercise in making meaning or an observation of a quality of the medium?

3. In Teen Image is seems that Price is calling attention to another quality of the digital – its tendency towards the clean in structure, the juvenile in language, and of course, the “personal” aspect of computer use that facilitates the viewing and proliferation of porn. He gets a bit wrapped up in this, but the connection stands: truth to the materials.

4. With regards to frenzy, Price examines another quality – limited resolution, and the mystery it inspires in the interpretation of images. This mystery is gone upon inspection of the actual object – “For example, a human body subjected to frenzies of processing is an aggressive and disturbing alienation, but the threat is also fascinating…” He parallels this quality to the indescribability of dreams.

5. Finally, Price jumps to the use of photographs in a further fleshing-out of his ideas. If you agree with my interpretation, you will see that the first book refers to the ideas of discussion and connected meaning in part 1, the second parallels generic analog advertising imagery to the ambiguity of the digital image (part 4), and so on. Another interpretation of this section might be that of connecting lists to lists, what I said in 2 about thought-webs. He is providing us with an example of all of the qualities he finds inherent in digital art by constructing a list of digital images from which we are to make meaning.

To jump in to this already exciting debate, I would like to speak in favor of both parties and try to point out what I think Price might be getting at. After a couple of reads, although he stumbles around with metaphors, I understand it to be an examination of the characteristics of the medium of digital art. I’ve broken his post down into a list(!).

1. It seems to me that the main debate here is over the connections between the images and sections of the essay composed by Price, and that any source of conflict over the work is derived from various readers “hastening to make startling connections among the raw material, tracing lines between points we didn’t even know existed.” This is ironic, and it seems that he’s pointing out the tendency that internet communication lends to discussions of topics. What really frustrates me is that we never seem to receive a decent explanation of what exactly “ritualized unknowing” is, particularly in context.

2. “To tame this frenzy we are offered the calming linearity of lists.” This essay is a list. The topics are not literally connected, rather Price has tamed (or at least made linear) his thought-web for our viewing. Is this a postmodern exercise in making meaning or an observation of a quality of the medium?

3. In Teen Image is seems that Price is calling attention to another quality of the digital – its tendency towards the clean in structure, the juvenile in language, and of course, the “personal” aspect of computer use that facilitates the viewing and proliferation of porn. He gets a bit wrapped up in this, but the connection stands: truth to the materials.

4. With regards to frenzy, Price examines another quality – limited resolution, and the mystery it inspires in the interpretation of images. This mystery is gone upon inspection of the actual object – “For example, a human body subjected to frenzies of processing is an aggressive and disturbing alienation, but the threat is also fascinating…” He parallels this quality to the indescribability of dreams.

5. Finally, Price jumps to the use of photographs in a further fleshing-out of his ideas. If you agree with my interpretation, you will see that the first book refers to the ideas of discussion and connected meaning in part 1, the second parallels generic analog advertising imagery to the ambiguity of the digital image (part 4), and so on. Another interpretation of this section might be that of connecting lists to lists, what I said in 2 about thought-webs. He is providing us with an example of all of the qualities he finds inherent in digital art by constructing a list of digital images from which we are to make meaning.

…and it looks like my formatting was lost. Another quality of translations of language in the medium, I guess. 🙂

…and it looks like my formatting was lost. Another quality of translations of language in the medium, I guess. 🙂

To be kind you could call Price’s writing “delphic”–a series of disconnected but coherent-ish phrases into which people read deep things. Robert Smithson rambled a bit and made strange connections but you knew he had a point and you learned something. Price is Smithson for the current art world: no passion, nothing at stake, no one is offended. Language that sounds critical is immediately rescinded or qualified. Just consider how many times the word “seem” is used on this page: “it often seems that any information or knowledge in these pages is glimpsed only through a slight fog of uncertainty”; “This seems like a promising answer…”; “Sometimes it seems as if the text was generated to explain the picture…”; “It seems you are more interested in books than the Net”; [Seth] seems totally in awe [of the Internet]”; “the seeming power to resolve all differences”; “To describe the exchanges that take place there, then, as partaking in a regime of spirited generosity seems to me a misreading…”; “More and more the shift on the web at least seems to be away from Tim Berners-Lee’s model…”; “Ekphrasis of these hoards seems increasingly unlikely”; “it seems that he’s pointing out the tendency that internet communication lends to…”; “it seems that Price is calling attention to another quality of the digital…” That’s a lot of seeming. The controversy here is not over the meaning of the essay but whether essays that seem to have meaning are valuable.

To be kind you could call Price’s writing “delphic”–a series of disconnected but coherent-ish phrases into which people read deep things. Robert Smithson rambled a bit and made strange connections but you knew he had a point and you learned something. Price is Smithson for the current art world: no passion, nothing at stake, no one is offended. Language that sounds critical is immediately rescinded or qualified. Just consider how many times the word “seem” is used on this page: “it often seems that any information or knowledge in these pages is glimpsed only through a slight fog of uncertainty”; “This seems like a promising answer…”; “Sometimes it seems as if the text was generated to explain the picture…”; “It seems you are more interested in books than the Net”; [Seth] seems totally in awe [of the Internet]”; “the seeming power to resolve all differences”; “To describe the exchanges that take place there, then, as partaking in a regime of spirited generosity seems to me a misreading…”; “More and more the shift on the web at least seems to be away from Tim Berners-Lee’s model…”; “Ekphrasis of these hoards seems increasingly unlikely”; “it seems that he’s pointing out the tendency that internet communication lends to…”; “it seems that Price is calling attention to another quality of the digital…” That’s a lot of seeming. The controversy here is not over the meaning of the essay but whether essays that seem to have meaning are valuable.

Poems and songs are “delphic,” and it’s hard to deny their value. “Apophenia” is another term that can describe the seeming-meaning-hoarding that Price’s piece has engendered here.

Barthes wrote of “the pleasure of System” that adopting methods of classification and list-making provided him. He cited Charles Fourier and Sade as “great classifiers,” and even a brief skim of their works illustrates how the ordering/listing of great quantities of the most exotic information imparts an authority–a seeming-meaning–to their contents. Or, as Price’s caption to Porter’s book suggests, “juxtaposing elements that might be stored hundreds or thousands of miles apart, giving an illusion of spatial continuity.” Proximity creates meaning, however uncertain we are of the combinations or the methods by which they were combined.

There is also a nice play to be had with the homophones “seem” and “seam,” as those moments where meaning is offered can also be sites where disparate texts and images are being stitched together to generate meaning. “An array of stitches” is what we’re provided with here and, thanks to the renewal of this comment-list, actively contributing to ourselves.

Poems and songs are “delphic,” and it’s hard to deny their value. “Apophenia” is another term that can describe the seeming-meaning-hoarding that Price’s piece has engendered here.

Barthes wrote of “the pleasure of System” that adopting methods of classification and list-making provided him. He cited Charles Fourier and Sade as “great classifiers,” and even a brief skim of their works illustrates how the ordering/listing of great quantities of the most exotic information imparts an authority–a seeming-meaning–to their contents. Or, as Price’s caption to Porter’s book suggests, “juxtaposing elements that might be stored hundreds or thousands of miles apart, giving an illusion of spatial continuity.” Proximity creates meaning, however uncertain we are of the combinations or the methods by which they were combined.

There is also a nice play to be had with the homophones “seem” and “seam,” as those moments where meaning is offered can also be sites where disparate texts and images are being stitched together to generate meaning. “An array of stitches” is what we’re provided with here and, thanks to the renewal of this comment-list, actively contributing to ourselves.

Hi Tom, You have a point. Your point is points are either clearly stated and literal and this is the only form of criticism or they are evasive and therefore a symptom of our current art world. (It was always better in the old days.) You say you knew Smithson had a point. What was his point? And why didn’t he just come out and say it?

Hi Tom, You have a point. Your point is points are either clearly stated and literal and this is the only form of criticism or they are evasive and therefore a symptom of our current art world. (It was always better in the old days.) You say you knew Smithson had a point. What was his point? And why didn’t he just come out and say it?

Art doesn’t solve problems, it creates new ones

Art doesn’t solve problems, it creates new ones

So… we have an essay comprised of a list (or is it a hoard?) of cobbled-together topics, and a frenzy of seemingly unwitting commenters hastening to make startling connections, tracing lines between points they didn’t even know existed. Call me crazy, but the opening ceremony of the beijing olympics was less choreographed than this.

So… we have an essay comprised of a list (or is it a hoard?) of cobbled-together topics, and a frenzy of seemingly unwitting commenters hastening to make startling connections, tracing lines between points they didn’t even know existed. Call me crazy, but the opening ceremony of the beijing olympics was less choreographed than this.

http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/0,1518,659577,00.html

http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/0,1518,659577,00.html

For those who think the term “hoarding” might not be pejorative, please note that Wikipedia has a discussion of “digital hoarding” as a mental disorder: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compulsive_hoarding (I learned about this on the Internet.)

For those who think the term “hoarding” might not be pejorative, please note that Wikipedia has a discussion of “digital hoarding” as a mental disorder: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compulsive_hoarding (I learned about this on the Internet.)

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 2 trackbacks }