I have a problem with Laurel Nakadate. It has nothing to do with her thighs and everything to do with Craigslist and her lacy panties. In a recent interview with Miranda Siegel for New York Magazine, she makes herself out to be a victim:

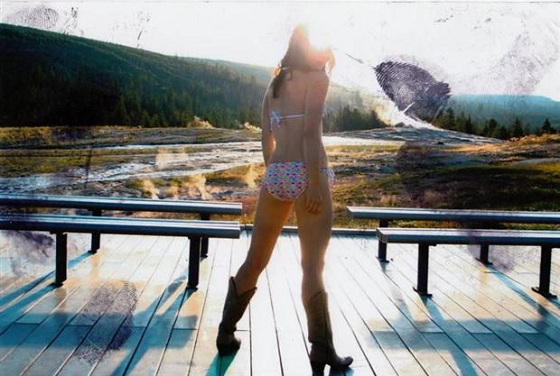

Pulling out “anti-feminist” card in a situation like this is like telling someone they're racist, anti-Semitic, homophobic, or ageist for not liking an artist who focuses on one of these topics. Nakadate puts her own body on display in her works; there's no way that people aren't going to take notice. With performance and video, the body viewed on-screen isn't a non-issue; it's part-and-parcel of the artwork. Nakadate’s body takes on a starring role in her works and it seems like she’s the only one who won’t admit it.

I'm not bothered by Nakadate's relative attractiveness or her proclivity for tarty underwear; I'm bothered by her refusal, here, to own up to the obvious juxtapositions her works present between young and old; male and female; and, of course, fuckworthy and repulsive.

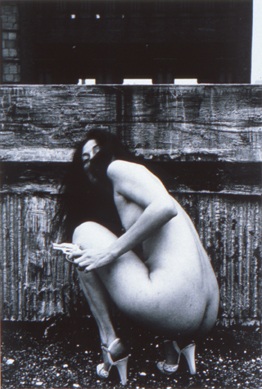

There are plenty of precedents in contemporary art of performance artists who are also hot. Hannah Wilke's a great case. She was gorgeous, but that never becomes a topic for criticism until the clothes come off. In Snatch Shots with Ray Guns (1978), which is exactly what you think it will be, Wilke aims her ass at the camera. She also got naked for things like exhibition announcements. Unlike Nakadate, Wilke didn't shy away from the self-awareness of her very public postures. Cindy Sherman, whose Untitled Film Stills began around the same time as Snatch Shots, kept her own body out of criticism because she obscured it through layers of make-up, wigs, and props.

It may appear a bit strange that critics like Ken Johnson focus so much on biography in Nakadate's work—“she is a fit and attractive woman in her mid-30s who has an M.F.A. from Yale”—but the glaring fact is that biography is an inescapable criticism when a performer focuses so much of their work on their own body. If Nakadate outsourced her performances or if she were a non-figurative painter, I'd be hounding on Ken Johnson's criticism. Instead, nobody's to blame except Nakadate; she brought this biographical interpretation on herself due to her choice of subject matter. She acknowledges this slightly in the same New York Magazine issue when she begins to bloviate about her position in art history:

After hundreds of years of art history, a young half-Asian girl meets older white men, and she's the predator? Suddenly no one can take it?

Nakadate's not doing anything that hasn't been done before—in the hundreds of years of Western art history. Regardless of whether or not you're anti-feminist, there's plenty of reasons to dislike Laurel Nakadate's work. My choice: her works are too simple.

365 Days: A Catalogue of Tears (2010-11) could have been ripped from an undergrad photography course assignment: take a photo of yourself repeating the same action everyday; then read about how photographs always lie about real life (re: Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, Walter Benjamin). Lessons 1-10 (2001), which “purports to be a montage of scenes from a series of Sundays Nakadate spent posing for a slovenly balding man who advertised for an artist's model on Craigslist,” presents a backwards view of the “scary internet,” a world that's full of sexual deviants preying on innocent teenagers in chat rooms. Nakadate's use of Craigslist as a haven for those less-than desirable types plays into these outdated stereotypes, leaving no room for gray area or nuance. Craigslist and the internet are more complicated than the version Nakadate puts forth. It's a good reason to dislike the work—and it doesn't resort to dirty tricks like calling someone out for being anti-feminist.

{ 75 comments }

Hey Corinna, I’m so glad you brought this up. This argument has been kicking around the office since her PS1 show.Â

Mostly I agree with you; the work is simple, and I’m starting to think twice after that James Franco collaboration.Â

I lose you at Hannah Wilke, though. Wilke wasn’t taken very seriously at all for most of her career because of her sexiness. Supposedly her place in art wasn’t cemented until she took nude photos of herself as a much older woman dying of cancer. Â

I think, then, a biographical critique of Nakadate’s work is open for debate, but the “anti-feminist” complaint is valid when she’s literally faulted for her physical attractiveness simply because she chooses to use her body in her work. Are you saying that Cindy Sherman should have covered up with prosthetics to avoid this trap? Â

Jen Schwarting recently discussed the Wilke-Nakadate parallel and her “anti-feminist” critics, which I have to agree with.  She notes that: “…Wilke’s critique [her striptease] was purposefully complicated by the pleasure audiences took in looking. If the viewer felt conflicted—or even manipulated—that was entirely the point.” I think Nakadate, too, is asking for a more open read.  I think the problem lies in the use of such black-and-white terms as her own “anti-feminist.” Â

http://www.papermonument.com/issue-two/you-dirty-worthless-slut/

Hey Whitney,

The main problem lies in anyone who’s putting their own body forward so blatantly; of course people are going to bring up your biography if you’re in the work. That’s my main issue with Nakadate’s “anti-feminist” – whatever that means – comment. I wanted to bring up what I don’t think people are disussing, that there’s good reasons to hate the work that have nothing to do with what LN looks like.Hannah Wilke was taken less seriously than, say, Cindy Sherman who was making work at the same time. And yeah, it’s because she didn’t shy away from covering up her body. This points to Catch-22 within first-wave feminism: How do I embrace my feminine identity, my vagina, et al. while avoiding the male gaze? Well, you can’t do that. That’s a history lesson, of sorts, for artists now, like Nakadate who’s claiming, “What’s the big deal that I’m doing this?” I know that if I put my ass on view, people are going to talk about it. So, Sherman’s making work when the body art craze with people like Hannah Wilke and Ana Mendieta is ending. There was a disgust, particularly with female art critics, who disagreed with the focus on what an artist looked like. So, obviously, they went in the opposite direction: in order to get away from smug comments about what the artist looks like, well, they had to start making other types of work that got away from the body – or that didn’t focus on their own body, re: Sherman’s dressing up and even her vomit photographs that show the inside of the body, not just the veneer.More than just an art debate, I hope some of the points in my essay bring up the difficult lines crossed in life, everyday. Should I wear a big, brown sack everyday so that people won’t focus on what I look like? What about my glasses? Should I wear glasses and stop wearing make up? Maybe I won’t paint my nails today. These are issues I wrestle with, too.Â

It seems to me from the quote you posted that she’s not actually saying it’s anti-feminist to comment on her body/appearance, since that’s obviously something in the work (especially in the projects that hinge specifically on her sexual attractiveness to the men she meets on craigslist, etc.,) but to attack her specifically BECAUSE she is attractive.Â

Nakadate’s work relies on what she looks like, what she wears, and how she poses. Her works have everything to do with her appearance; therefore, it’s silly that she’s criticizing people for what’s going on in the work.

I’m deeply suspicious that anybody has attacked her specifically because she’s attractive, without it having something to do with the work. I think that was a strawman to begin with. If this were occurring on a serious scale, we might have heard something from any number of attractive female artists who do not also have a clear investment in their attractiveness as a tool for art-making. The whole thing sounds to me very much like the pre-emptive accusations of racism that came out of the Herman Cain campaign.Â

Also:Â http://youtu.be/hz8ul-gmLyA

I don’t necessarily disagree that it’s a strawman argument on Nakadate’s part; my point was more that Corinna’s post seems to be extending the “anti-feminist” remark to imply that Nakadate was saying any commentary about her looks whatsoever are anti-feminist, which isn’t how I read it.Â

I disagree. Nakadate is implying that anyone who talks about her looks is anti-feminist. Nakadate said that anyone who doesn’t like her work because she’s attractive is anti-feminist. I doubt that anyone has come out and said that her works fail because of her looks. Instead, what’s happening is that critics like Ken Johnson describe her works in terms of her physical appearance. Because there hasn’t been any actual criticism about Nakadate’s works because of her looks, Nakadate is actually having a problem with all of the descriptions and all the commentary about her work that involves her looks, saying it’s anti-feminist.Â

I’m offering a way out of describing Nakadate’s appearance in criticism. We can focus on the overly simple logic that her works rely on.

I take issue with your historical framing of Hannah Wilke.  Wilke’s attractiveness was a consistent criticism throughout her career, whether she had clothes on or not, which lead to “self aware” performances involving putting chewed-up bubble gum all over her naked body, or taking photographs of her cancerous flesh in decay.  The female body shouldn’t have to be embarrassed, mutilated, or diseased, in order to be taken seriously.  It always bothered me that Wilke went that direction.  When you look at 60s/70s Carolee Schneeman, for example, in “Meat Joy” or “Interior Scroll”, there’s celebration in her sexuality.  It’s beautiful.  You seem to assert that female performance must operate at either extreme:  either completely in-your-face sexuality, or masked with “layers of make-up, wigs and props”, which, hate to say it, sounds pretty damned anti-feminist.

I knew that rant in the comments section might be trouble. Of course the female body shouldn’t be scarred (re: Wilke’s “Starification” series) in order for it to be taken seriously in performance. In an ideal world, artists, writers, etc. would be able to do whatever the hell they want in performance without someone bringing up their personal life. And like how almost every piece about Wilke I’ve ever read brings up how she dated Claes Oldenburg. That’s trashy.

About the Sherman/Wilke kerfuffle: The Sherman/Wilke comparison is an historical one, my opinions on which of these two artists aside. I wanted to mark that in one case in time, the idea was more or less, “Let’s get away from using our own bodies in order to escape the troubled discussion of our bodies.” The escape plan, if I agreed with it as  valid for today, yeah, would be kind of anti-feminist. We’re postmodern, whether we like it or not; let’s not escape the discussion anymore.Â

In Nakadate’s case, there’s reason to dislike her work that has nothing to do with what she looks like. I think that’s a better route for critics to take when discussing her work from now on. Then maybe we won’t have to deal with weird outbursts over who’s a good feminist or not.

I’m having trouble with your use of Sherman here. Sherman is, technically speaking, present in her work physically, but she’s quite explicit about the fact that they’re not self-portraits, which can’t be said for Wilke. I also think it’s a mischaracterization of Sherman’s work to say that dressing up was a means of explicitly escaping a discussion of her body. The reason we don’t talk about Sherman’s body in the same way we do about Wilke’s (or, for that matter, Nakadate’s) is that it’s beside the point — it’s not what the work is about.

Â

Wilke wasn’t making self-portraits in the 1970s. Her “Starification” series and the series I mentioned in this essay aren’t self-portraits. Saying that Sherman is “quite explicit about the fact that they’re not self-portraits, which can’t be said for Wilke” isn’t true when Wilke wasn’t making self-portraits either.

The discussion of what does or doesn’t constitute a self-portrait is one we can save for another time, but my point in bringing up that distinction is that in Wilke’s SOS series and in her other body-based work, regardless of whether you want to see them as self-portraits, is that the body in the images is read as Wilke’s body. In Sherman’s work, on the other hand, we know that it is, of course, literally Sherman’s body who performs for the camera, but when we see the images, there’s an intended suspension of disbelief involved — we’re not meant to read them as depicting “Cindy Sherman’s body” but the body of whatever character or persona she’s adopting in the image.

I only go on Craigslist in hopes of running into someone of Nakadate’s attractiveness… but sadly, she never appears.

IIRC shiny Pokemon occur at a 1/8192 rate.Â

I dunno if that looks racist now but I want to make clear that I just really like Pokemon.

Hi Corinna et al,

Agreed, great topic, seems as if this were on the tips of all our tongues for years. Though, I do have to agree with Whitney’s taking issue with this characterization of Wilke and the parallel to Nakadate, though I cringe at the notion that Wilke wasn’t taken seriously as an artist before her lymphoma. As Lindsay duly noted, it’s pretty fucked up that Wilke was only redeemed by some of her more recalcitrant critics after she deteriorated from disease and continued to photograph her body. This shouldn’t be a legitimizing factor. Further, Wilke has been taken seriously as an artist for decades–obviously this is why male-separatist feminists found her to be threatening. Anyway, this article seems to be well-timed. Simone Menegoi, an Italian curator and editor, wrote a sensitively hewn, superbly researched article on the reputation of Wilke in the most recent issue of Kaleidoscope, which I reference in part below.

I think it’s important to consider that Wilke and Nakadate are not contemporaries, and a parallel between them should be constructed with pause. The willingness of Nakadate to exhibit her body comes with a different politic than of that of Wilke–I’d argue that the image of the nude female body bears a considerably mitigated impact on a contemporary individual due to the proliferation of this image today. And in some sense, I would say that Nakadate has enjoyed the fruits of much of Wilke’s toils, and consequently Nakadate’s work hits me with far less gravity. In my mind, she hasn’t innovated or rendered contemporary any of the ideas digested by Wilke. Yet, what hasn’t changed since the first-wave discussions of Wilke’s work, is that the debates surrounding the merit of both Wilke and Nakadate still circle around where their intentions lie, namely, in whether or not they are exhibitionists. Long forgotten and generally elided is Wilke’s earlier work, ceramic and latex “cunts” (slaps of clay or latex folded in a minimal construction to resemble labia) and the taboo speech she uses to contextualize them. Speaking of parallels, I haven’t really found this undergirding and dynamism in Nakadate’s oeuvre.

Must all work involving a nude female body default to an act of its politicization? Perhaps both Nakadate and Wilke evade this. Menegoi sums this up nicely, “Wilke was aware of how beauty is reified, manipulated and exploited; what seemed to interest her, however, was not rejecting or reversing the canons and stereotypes of beauty, but rather exploring them in the double role of subject and object, of a politicized, conscious woman who also happened to be a beautiful one.” Also noted by Menegoi is Wilke’s strained relationships with many female (namely radical feminist) artists of her era. She actually accused the feminist study group Heresies of not being interested in her work because she was “more beautiful than any of them.” Yuck.

But, as Rachel has aptly noted, the most potent criticism of Nakdate’s work is that she USES her attractiveness uncritically, perhaps unlike Wilke, which begets accusations of exhibitionism. This is distinct from the situation mentioned above, in which Wilke felt elided BECAUSE she’s attractive, whatever the case actually was.

Art audiences sometimes demand that artists be moral guides. Artists are supposed to make the world better.

However, equally as important is for artists to be a mirror of society, to reflect ourselves back to us. Nakadate does this quite well.Â

Nakadate isn’t attempting to subvert the male gaze or actualize female empowerment. Her strongest work illustrates the power dynamics between men and women. I wonder Corinna if you’ve watched any of her videos all the way through? Paraphrasing her projects such as Lessons 1-10 often does them a disservice because the power of those works is within the videos, not the story of their come to being. In these videos Nakadate gives us a powerful demonstration on how power and sexuality function today, despite feminist gains. We see Laurel not taking advantage of “pathetic men” but showing who has power in the situation, when and why. Nakadate may be beautiful, but the men in her video are stronger. Both Nakadate and the men in these videos appear vulnerable and exploited (or self exploited) but also powerful in their acceptance to trust one another to not take advantage of them in a way they feel completely uncomfortable with.

I can understand Nakadate’s frustration at people being bothered by her looks and agree with Rachel when Nakadate’s “anti feminist” remark may have been targeted specifically at people hating her for using her beauty. But in Nakadate’s case, the personal is political, and Nakadate’s choice to make auto-biographical work (at least it is thematically) must take into account her experiences as a young woman.Â

“People hating her for using her beauty” like who?

MS: You’re also attractive, and that bothers people.

“But Miranda Siegal started it!” isn’t going to cut it. Is there any evidence that anyone in real life is actually bothered by what Laurel Nakadate looks like? Because if not, I don’t think we should continue acting as though something meaningful has been expressed here.

Not to leap on you in particular, but just as a matter of principle. I can throw out some comments at all the people who hate me because I’m so cool, but I don’t think I deserve any sympathy or critical attention for saying that.

I worshipped Laurel Nakadate in my undergrad and at some point, made work like hers. It’s different from all the literal antagonism from 70s predecessors like Lynda Benglis and Martha Wilson. Nakadate seemed to possess a pleasure in performing stereotypes, which is something I also see in Ann Hirsch’s (Scandalishious) work. There’s a sense of vulnerability and risk that I don’t see in gallery art and a credible sense that she can reclaim female stereotypes in the real world.Â

I agree with Corinna that more criticism has been directed at her beauty and life story–instead of her politics (which many a [male] viewer would find juvenile and irrelevant).  As a distinctively female perspective, if this were the kind of work women made were featured in galleries as much as resonantly-AbEx paintings or minimal drawings (imo boring!), this wouldn’t be viewed as “juvenile” either. Who’s perspectives and aesthetics are we supporting in the larger world of art?However I find the comments about her work appearing “done before” and that “anyone could do it” tend to close off a lot of conversation about the politics and social affects of her work. Everyone is producing under the burden of history now… beyond that I want to think about how her practice is transforming the definition/categorization of “feminist” art.

One of my profs also said that she “flaunts feminism”. What makes her work seem easy? Making an effort to meet people and maintaining a persona is an ongoing effort. We may recourse to the beauty myth to think her works happen just because she is beautiful. This is a fallacy. What if a gay trans-man made this work featuring himself? Would the political analyses and moralizations we apply to it be the same?

I take issue with how progressive her work is for feminist discourse. Her performance of raunch and roleplay as power appears to mistake sexual agency for political agency.Â

Strategic essentialism fails when it relies on a binaric marginality and Nakadate’s work hinges on that: performing the hysteric, hetero-desired subject without offering a kind of transgression/violation of those categories in the end. So I feel her work veers on blowing open old stereotypes of women instead of destabilizing them. Also, a relational work crit on her invitation of old ugly men as subjects also relies on them not knowing about contemporary art. in terms of looking at the camera and agency: Self-reference/awareness seems to be a sort of fallback for artists now, I’m drawn to the play and vulnerability in the pieces. It wouldn’t have been funny if she were assaulted in any of her chance-encounter vids. People don’t imagine that happening when they watch her work because of the soundtracks and pop references. She made it easy to digest and less awkward than it could have been irl.

If you are a woman and find her process laughable maybe one needs to reconsider how we view women who appear more sexually available – Is this threatening for other men and women, and are your views shaped by a male-authored perspective? Everyone’s feminism is a different feminism; no one feminism can make all feminists happy.

My biggest criticism of her work in relation to its aesthetics and process is that she doesn’t put any of it online (esp. on YouTube). This protects it from the very dissent and male hazing that justifies its existence in the first place.

Thanks for the comment, Jennifer. I’m happy that this essay has sparked so much debate. It makes me hope that feminism is still relevant. In grad school, feminism wasn’t part of the debate at all; we were too post-everything in Chicago.Â

It makes sense that Nakadate would be an undergrad hero because her work seems so “textbook.” Getting away from biographical criticism is a good thing: in general, we don’t need to know where an artist was born. Per the YouTube comment, we’re in agreement that there’s ways to dislike Nakadate that have nothing to do with what she’s wearing or her biography. Nakadate’s doesn’t get how the internet works and, as you said, a relational crit of her work doesn’t work either.Â

Her interview is the same as the art. Link-bait.

I sometimes think that attractive women should wear burkas in the summer in New York. Â All that shameful exposure of desirable flesh is so evil.Â

How about it’s just not good work. Man or woman.

I’m sick to death of the same of stereotypes dressed up in new ideology. Â It looks, walks, and quacks like a duck, but it’s NOT a duck, because the duck says so. Â I’m still waiting for an artist to make work that breaks out of these exhausted gender paradigms. Â I have a feeling I’ll be waiting a long time, because the kind of work under discussion here is the kind of work the establishment loooooves to hash and re-hash while being titillated without discomfort because the status quo isn’t being challenged. Â The ambition in this work is to be noticed, period. Â Very successful in that regard, apparently.

I’m sick to death of the same of stereotypes dressed up in new ideology. Â It looks, walks, and quacks like a duck, but it’s NOT a duck, because the duck says so. Â I’m still waiting for an artist to make work that breaks out of these exhausted gender paradigms. Â I have a feeling I’ll be waiting a long time, because the kind of work under discussion here is the kind of work the establishment loooooves to hash and re-hash while being titillated without discomfort because the status quo isn’t being challenged. Â The ambition in this work is to be noticed, period. Â Very successful in that regard, apparently.

I’m sick to death of the same of stereotypes dressed up in new ideology. Â It looks, walks, and quacks like a duck, but it’s NOT a duck, because the duck says so. Â I’m still waiting for an artist to make work that breaks out of these exhausted gender paradigms. Â I have a feeling I’ll be waiting a long time, because the kind of work under discussion here is the kind of work the establishment loooooves to hash and re-hash while being titillated without discomfort because the status quo isn’t being challenged. Â The ambition in this work is to be noticed, period. Â Very successful in that regard, apparently.

I think she’s a predator who records her using people in a dehumanizing and degrading manner. I fail to see the art. Reminds me of a young woman in Poland who slit the throat of a pony and videoed it’s dying process, as her grad piece in art school. It took several hours to die. It has been put forth by cognitive therapists that loneliness and isolation are symptom of depression. She is therefore preying upon and taking advantage of the ill who are trying to get their needs met for communication, companionship and sex, then she calls them ‘pathetic’. Ya, I have no respect for her or her very stupid photos and videos.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iot1-y9O4Po&feature=related

I think she’s a predator who records her using people in a dehumanizing and degrading manner. I fail to see the art. Reminds me of a young woman in Poland who slit the throat of a pony and videoed it’s dying process, as her grad piece in art school. It took several hours to die. It has been put forth by cognitive therapists that loneliness and isolation are symptom of depression. She is therefore preying upon and taking advantage of the ill who are trying to get their needs met for communication, companionship and sex, then she calls them ‘pathetic’. Ya, I have no respect for her or her very stupid photos and videos.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iot1-y9O4Po&feature=related

That’s a great, pretty disgusting video interview with “Vice.”Â

That’s a great, pretty disgusting video interview with “Vice.”Â

That’s a great, pretty disgusting video interview with “Vice.”Â

I think she’s a predator who records her using people in a dehumanizing and degrading manner. I fail to see the art. Reminds me of a young woman in Poland who slit the throat of a pony and videoed it’s dying process, as her grad piece in art school. It took several hours to die. It has been put forth by cognitive therapists that loneliness and isolation are symptom of depression. She is therefore preying upon and taking advantage of the ill who are trying to get their needs met for communication, companionship and sex, then she calls them ‘pathetic’. Ya, I have no respect for her or her very stupid photos and videos.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iot1-y9O4Po&feature=related

I like art that is challenging and morally ambiguous. But what really gets me wet is when art is _generous_. Nakadate is just too self-obsessed to be interesting.

I like art that is challenging and morally ambiguous. But what really gets me wet is when art is _generous_. Nakadate is just too self-obsessed to be interesting.

I like art that is challenging and morally ambiguous. But what really gets me wet is when art is _generous_. Nakadate is just too self-obsessed to be interesting.

It has been ever thus: men, especially those of a certain age, become unhinged at the sight of a young woman in her underwear. We know and accept this, always with the hope, however, that this derangement won’t interfere with their professionalism. Compared with how Monica Lewinsky and her thong affected history, an art exhibition is a minor event—yet Klaus Biesenbach, who organized  Laurel Nakadate’s “Only the Lonely†atPS 1 (through August 8) and Ken Johnson who reviewed it enthusiastically in yesterday’s Times (but is still wondering if Christian Marclay’s brilliant  The Clock could be just a “stunt,†see post below), might have considered that they were not thinking entirely with their heads.

While she also exhibited videos (such as one I found particularly mean-spirited, of herself dancing like Britney Spears in front of desperately lonely men), most annoying is 365 Days: A Catalogue of Tears (2010), where Nakadate worked up a state of sadness for a portion of each day, and then photographed herself—posing in her undies and often topless—before, after or during the shedding of supposedly real tears. Johnson asks, sensibly enough, “Since she is a fit and attractive woman in her mid-30s who has an M.F.A. from Yale and is now enjoying this retrospective, you might wonder what she has to be so lachrymose about,“ but then backtracks by saying, “A more sympathetic view is that she has been tapping into a river of grief and loneliness running under the surface of American life.†Now there’s a sentence that begs for amplification and justification: just what “river of grief and loneliness†is Johnson talking about anyway? And why the requirement to be sympathetic?

In her work, this poor girl who has so much she must force herself to feel unhappy every day, makes a mockery of real sadness. While writing this I’ve been talking with a good friend whose aunt just died, and who is attempting to comfort his beloved 92-year-old grandparents. Do we want to see the pictures? Try glamorizing that scenario.Â

Despite its weak theme, the installation is impressive: framed in white and hung gallery-style in symmetrical rows that march toward an archway, these richly colored photographs turn the high-ceilinged rooms into a semblance of a Renaissance palace, streamlined for the 21st century. What’s really sad is that without Nakadate moping in them, most of the images could stand on their own. It’s pathetic that, given the times, artists feel the necessity to overlay perfectly good photography with art school conceits. Plus, whatever happened to subtlety? There are more evocative ways to convey sadness than the cliché of someone in tears.Â

The other really sad part is that if Nakadate were to have made herself happy every day, the results might actually have been interesting—but “happy,†unfortunately, is not very arty.

My conclusion is that this girl needs a job! Her next “performance†should be one where she photographs herself 365 days a year working in a convenience store. Marina Abramovic she is not.

artvent.blogspot.com

It has been ever thus: men, especially those of a certain age, become unhinged at the sight of a young woman in her underwear. We know and accept this, always with the hope, however, that this derangement won’t interfere with their professionalism. Compared with how Monica Lewinsky and her thong affected history, an art exhibition is a minor event—yet Klaus Biesenbach, who organized  Laurel Nakadate’s “Only the Lonely†atPS 1 (through August 8) and Ken Johnson who reviewed it enthusiastically in yesterday’s Times (but is still wondering if Christian Marclay’s brilliant  The Clock could be just a “stunt,†see post below), might have considered that they were not thinking entirely with their heads.

While she also exhibited videos (such as one I found particularly mean-spirited, of herself dancing like Britney Spears in front of desperately lonely men), most annoying is 365 Days: A Catalogue of Tears (2010), where Nakadate worked up a state of sadness for a portion of each day, and then photographed herself—posing in her undies and often topless—before, after or during the shedding of supposedly real tears. Johnson asks, sensibly enough, “Since she is a fit and attractive woman in her mid-30s who has an M.F.A. from Yale and is now enjoying this retrospective, you might wonder what she has to be so lachrymose about,“ but then backtracks by saying, “A more sympathetic view is that she has been tapping into a river of grief and loneliness running under the surface of American life.†Now there’s a sentence that begs for amplification and justification: just what “river of grief and loneliness†is Johnson talking about anyway? And why the requirement to be sympathetic?

In her work, this poor girl who has so much she must force herself to feel unhappy every day, makes a mockery of real sadness. While writing this I’ve been talking with a good friend whose aunt just died, and who is attempting to comfort his beloved 92-year-old grandparents. Do we want to see the pictures? Try glamorizing that scenario.Â

Despite its weak theme, the installation is impressive: framed in white and hung gallery-style in symmetrical rows that march toward an archway, these richly colored photographs turn the high-ceilinged rooms into a semblance of a Renaissance palace, streamlined for the 21st century. What’s really sad is that without Nakadate moping in them, most of the images could stand on their own. It’s pathetic that, given the times, artists feel the necessity to overlay perfectly good photography with art school conceits. Plus, whatever happened to subtlety? There are more evocative ways to convey sadness than the cliché of someone in tears.Â

The other really sad part is that if Nakadate were to have made herself happy every day, the results might actually have been interesting—but “happy,†unfortunately, is not very arty.

My conclusion is that this girl needs a job! Her next “performance†should be one where she photographs herself 365 days a year working in a convenience store. Marina Abramovic she is not.

artvent.blogspot.com

It has been ever thus: men, especially those of a certain age, become unhinged at the sight of a young woman in her underwear. We know and accept this, always with the hope, however, that this derangement won’t interfere with their professionalism. Compared with how Monica Lewinsky and her thong affected history, an art exhibition is a minor event—yet Klaus Biesenbach, who organized  Laurel Nakadate’s “Only the Lonely†atPS 1 (through August 8) and Ken Johnson who reviewed it enthusiastically in yesterday’s Times (but is still wondering if Christian Marclay’s brilliant  The Clock could be just a “stunt,†see post below), might have considered that they were not thinking entirely with their heads.

While she also exhibited videos (such as one I found particularly mean-spirited, of herself dancing like Britney Spears in front of desperately lonely men), most annoying is 365 Days: A Catalogue of Tears (2010), where Nakadate worked up a state of sadness for a portion of each day, and then photographed herself—posing in her undies and often topless—before, after or during the shedding of supposedly real tears. Johnson asks, sensibly enough, “Since she is a fit and attractive woman in her mid-30s who has an M.F.A. from Yale and is now enjoying this retrospective, you might wonder what she has to be so lachrymose about,“ but then backtracks by saying, “A more sympathetic view is that she has been tapping into a river of grief and loneliness running under the surface of American life.†Now there’s a sentence that begs for amplification and justification: just what “river of grief and loneliness†is Johnson talking about anyway? And why the requirement to be sympathetic?

In her work, this poor girl who has so much she must force herself to feel unhappy every day, makes a mockery of real sadness. While writing this I’ve been talking with a good friend whose aunt just died, and who is attempting to comfort his beloved 92-year-old grandparents. Do we want to see the pictures? Try glamorizing that scenario.Â

Despite its weak theme, the installation is impressive: framed in white and hung gallery-style in symmetrical rows that march toward an archway, these richly colored photographs turn the high-ceilinged rooms into a semblance of a Renaissance palace, streamlined for the 21st century. What’s really sad is that without Nakadate moping in them, most of the images could stand on their own. It’s pathetic that, given the times, artists feel the necessity to overlay perfectly good photography with art school conceits. Plus, whatever happened to subtlety? There are more evocative ways to convey sadness than the cliché of someone in tears.Â

The other really sad part is that if Nakadate were to have made herself happy every day, the results might actually have been interesting—but “happy,†unfortunately, is not very arty.

My conclusion is that this girl needs a job! Her next “performance†should be one where she photographs herself 365 days a year working in a convenience store. Marina Abramovic she is not.

artvent.blogspot.com

Hi Karen,

I’m happy that there’s been so much commentary, expressing, hopefully that feminism and feminist issues are still completely relevant for today’s art and creative practices. People should disagree; I’d rather have discourse than a plateau of complacency. No, of course Nakadate and Wilke aren’t doing the very same thing. I’m interested in the history of critical reception, of how artists are perceived by critics and press at certain points of their careers. The unfortunate lesson of Wilke’s career for someone like Nakadate is that if you’re using your attractiveness – self-aware or not – then, in all likelihood, people are going to leap on that one detail. And that sucks.

Hi Karen,

I’m happy that there’s been so much commentary, expressing, hopefully that feminism and feminist issues are still completely relevant for today’s art and creative practices. People should disagree; I’d rather have discourse than a plateau of complacency. No, of course Nakadate and Wilke aren’t doing the very same thing. I’m interested in the history of critical reception, of how artists are perceived by critics and press at certain points of their careers. The unfortunate lesson of Wilke’s career for someone like Nakadate is that if you’re using your attractiveness – self-aware or not – then, in all likelihood, people are going to leap on that one detail. And that sucks.

Hi Karen,

I’m happy that there’s been so much commentary, expressing, hopefully that feminism and feminist issues are still completely relevant for today’s art and creative practices. People should disagree; I’d rather have discourse than a plateau of complacency. No, of course Nakadate and Wilke aren’t doing the very same thing. I’m interested in the history of critical reception, of how artists are perceived by critics and press at certain points of their careers. The unfortunate lesson of Wilke’s career for someone like Nakadate is that if you’re using your attractiveness – self-aware or not – then, in all likelihood, people are going to leap on that one detail. And that sucks.

I’m going to try and be careful here, since I think commenting on this topic in the way that I intend might put me out there on a lil’ bit of a limb… But here goes nothing!

I had the chance to see the PS1 exhibition last spring and was confronted with a lot of mixed emotions, as – obviously – others did. But what I couldn’t let myself do was simply just walk away. I’d usually not give as much attention or time with a work/artist that I initially just don’t like right off the bat, but something about the show was incredibly compelling from a completely self/interior space. Although I thought that the 365 piece was not very moving, and eventually tainted my entire experience through an overwhelming apathy for what I felt to be forced/crocodile tears, I was able to ignore that main hallway enough to take more time with the video works.

I found myself enticed, wanting to watch, wanting to linger, wanting to be an audience member tempted and seduced. It’s not that I had a particular attraction to her at all, but the acts, performances, albiet cliched and occasionally stale, would sometimes add up just enough for me to like _the idea_ behind what was being presented. As a result, I became utterly embarrassed at this want/attraction, and this shyness created a complex situation of unrest within me that I felt compelled to go through in tandem with the works. As a result, I walked through the show with two parallel emotions, one of inherent distrust at playing upon my expectations/desires, and one of genuine intrigue. In this way, I wanted to see more, I wanted to metaphorically pull back the curtain as much as I could to really see what was going on, wanting to see if in fact I was attracted to this woman, or if in fact I was just interesting in the idea of a woman performing in this way. I continued to move around the various black box rooms and sitting down for about two hours in total searching for the idea of that performing woman to materialize fully, to accentuate herself not as passing as a teenager or a young girl, but as a woman of substance, a woman “worth more” than their surface. Perhaps this is central question of the work, “who is the real Laurel?” But the question never became more than a mere thought exercise, and thusly never became interesting, because I was only presented really with one perspective. I had no alternative, or very little personality to respond to, and as a result, the figure on the screen became ultimately one dimensional.

So I became uninterested “romantically” but then became interested emotionally or artistically by the realization that I was not even really looking at the work itself, but looking internally – or within myself – to the idea of a woman performing that way that Laurel does in her work. Truth be told, I think that a lot of the work is aesthetically boring, or also formally one-dimensional. Once I stopped looking at these works with a male gaze – which is what I think Laurel intends at first – but instead through the vision of a person engaged in contemporary ways of creating multiple/alternative identities, I started to check out. The veneer never got past itself. The falsified “tragedy” of a woman using her body for attention/affection never was never actualized since none of the initial elements of the tragedy were ever staged, and in a sense the paradoxical nature of this type of staging/performance (its self imposed horror/sadness as a result of one’s actions) never is fully developed or even put into play. As a result, the work never really became a critique, it only became exposition. Even if one can argue that this “peek into the underworld” is a critique, I was never certain who it was directed at: the expectations of these men (or men in general), the oppressive sexual depiction of women, or the art system that supports “attractive late 20s people” I always remind myself that “showing isn’t enough,” that a certain point action must occur, and that stances/commentary must explicitly come to light at some point in order for the materials of a process to work past their passive participation.

Your beautiful comment almost made me cry real tears. No joke.

Your beautiful comment almost made me cry real tears. No joke.

Your beautiful comment almost made me cry real tears. No joke.

I appreciate the thorough analysis Nicholas. I also wanted more on Laurel-as-artist because even her interview persona is a performance imo, and one she invented to quickly defend her critz. 365 days doesn’t invite much empathy because it looks like MySpace profile pics blown up in an expensive fashion and the expressions and relations feel staged.Â

I liked the vid Love Hotel though, where she pretended to be having sex with an invisible lover. It seems desiring, fun, and sort of sad–plausible that a woman might try it to see what their sexual actions look like on cam.  The best thing about critique is that there’s no right way to do it but the artist can never anticipate a standard reading either.

I wonder (and I wrote about this a bit before) if this is the double-bind “problem” with what we call “feminist”performance art. Women are caught between performing stereotypes to destabilize them, or upstaging male contemporaries (in”Where you’ll find me” LN does the Robert Frank style American roadtrip) in order to get across an empowered politic that may be ultimately viewed as unsavoury, insulting, or inaccessible to the public. What recourse do performance artists have? I feel like the gendered/raced body and the face is such a weighted signifier, never neutral. Compared to the symbolic gestures of her 70s predecessors I find Nakadate and other feminist contemporaries more cynical and ironic than before. A possibly postfeminism-as-feminism, “no one gives a shit anyway” kind of performance. In that case, I would go  big or go home instead of getting people together in a gallery to enjoy pad thai around each other.

I appreciate the thorough analysis Nicholas. I also wanted more on Laurel-as-artist because even her interview persona is a performance imo, and one she invented to quickly defend her critz. 365 days doesn’t invite much empathy because it looks like MySpace profile pics blown up in an expensive fashion and the expressions and relations feel staged.Â

I liked the vid Love Hotel though, where she pretended to be having sex with an invisible lover. It seems desiring, fun, and sort of sad–plausible that a woman might try it to see what their sexual actions look like on cam.  The best thing about critique is that there’s no right way to do it but the artist can never anticipate a standard reading either.

I wonder (and I wrote about this a bit before) if this is the double-bind “problem” with what we call “feminist”performance art. Women are caught between performing stereotypes to destabilize them, or upstaging male contemporaries (in”Where you’ll find me” LN does the Robert Frank style American roadtrip) in order to get across an empowered politic that may be ultimately viewed as unsavoury, insulting, or inaccessible to the public. What recourse do performance artists have? I feel like the gendered/raced body and the face is such a weighted signifier, never neutral. Compared to the symbolic gestures of her 70s predecessors I find Nakadate and other feminist contemporaries more cynical and ironic than before. A possibly postfeminism-as-feminism, “no one gives a shit anyway” kind of performance. In that case, I would go  big or go home instead of getting people together in a gallery to enjoy pad thai around each other.

I appreciate the thorough analysis Nicholas. I also wanted more on Laurel-as-artist because even her interview persona is a performance imo, and one she invented to quickly defend her critz. 365 days doesn’t invite much empathy because it looks like MySpace profile pics blown up in an expensive fashion and the expressions and relations feel staged.Â

I liked the vid Love Hotel though, where she pretended to be having sex with an invisible lover. It seems desiring, fun, and sort of sad–plausible that a woman might try it to see what their sexual actions look like on cam.  The best thing about critique is that there’s no right way to do it but the artist can never anticipate a standard reading either.

I wonder (and I wrote about this a bit before) if this is the double-bind “problem” with what we call “feminist”performance art. Women are caught between performing stereotypes to destabilize them, or upstaging male contemporaries (in”Where you’ll find me” LN does the Robert Frank style American roadtrip) in order to get across an empowered politic that may be ultimately viewed as unsavoury, insulting, or inaccessible to the public. What recourse do performance artists have? I feel like the gendered/raced body and the face is such a weighted signifier, never neutral. Compared to the symbolic gestures of her 70s predecessors I find Nakadate and other feminist contemporaries more cynical and ironic than before. A possibly postfeminism-as-feminism, “no one gives a shit anyway” kind of performance. In that case, I would go  big or go home instead of getting people together in a gallery to enjoy pad thai around each other.

I’m going to try and be careful here, since I think commenting on this topic in the way that I intend might put me out there on a lil’ bit of a limb… But here goes nothing!

I had the chance to see the PS1 exhibition last spring and was confronted with a lot of mixed emotions, as – obviously – others did. But what I couldn’t let myself do was simply just walk away. I’d usually not give as much attention or time with a work/artist that I initially just don’t like right off the bat, but something about the show was incredibly compelling from a completely self/interior space. Although I thought that the 365 piece was not very moving, and eventually tainted my entire experience through an overwhelming apathy for what I felt to be forced/crocodile tears, I was able to ignore that main hallway enough to take more time with the video works.

I found myself enticed, wanting to watch, wanting to linger, wanting to be an audience member tempted and seduced. It’s not that I had a particular attraction to her at all, but the acts, performances, albiet cliched and occasionally stale, would sometimes add up just enough for me to like _the idea_ behind what was being presented. As a result, I became utterly embarrassed at this want/attraction, and this shyness created a complex situation of unrest within me that I felt compelled to go through in tandem with the works. As a result, I walked through the show with two parallel emotions, one of inherent distrust at playing upon my expectations/desires, and one of genuine intrigue. In this way, I wanted to see more, I wanted to metaphorically pull back the curtain as much as I could to really see what was going on, wanting to see if in fact I was attracted to this woman, or if in fact I was just interesting in the idea of a woman performing in this way. I continued to move around the various black box rooms and sitting down for about two hours in total searching for the idea of that performing woman to materialize fully, to accentuate herself not as passing as a teenager or a young girl, but as a woman of substance, a woman “worth more” than their surface. Perhaps this is central question of the work, “who is the real Laurel?” But the question never became more than a mere thought exercise, and thusly never became interesting, because I was only presented really with one perspective. I had no alternative, or very little personality to respond to, and as a result, the figure on the screen became ultimately one dimensional.

So I became uninterested “romantically” but then became interested emotionally or artistically by the realization that I was not even really looking at the work itself, but looking internally – or within myself – to the idea of a woman performing that way that Laurel does in her work. Truth be told, I think that a lot of the work is aesthetically boring, or also formally one-dimensional. Once I stopped looking at these works with a male gaze – which is what I think Laurel intends at first – but instead through the vision of a person engaged in contemporary ways of creating multiple/alternative identities, I started to check out. The veneer never got past itself. The falsified “tragedy” of a woman using her body for attention/affection never was never actualized since none of the initial elements of the tragedy were ever staged, and in a sense the paradoxical nature of this type of staging/performance (its self imposed horror/sadness as a result of one’s actions) never is fully developed or even put into play. As a result, the work never really became a critique, it only became exposition. Even if one can argue that this “peek into the underworld” is a critique, I was never certain who it was directed at: the expectations of these men (or men in general), the oppressive sexual depiction of women, or the art system that supports “attractive late 20s people” I always remind myself that “showing isn’t enough,” that a certain point action must occur, and that stances/commentary must explicitly come to light at some point in order for the materials of a process to work past their passive participation.

I’m going to try and be careful here, since I think commenting on this topic in the way that I intend might put me out there on a lil’ bit of a limb… But here goes nothing!

I had the chance to see the PS1 exhibition last spring and was confronted with a lot of mixed emotions, as – obviously – others did. But what I couldn’t let myself do was simply just walk away. I’d usually not give as much attention or time with a work/artist that I initially just don’t like right off the bat, but something about the show was incredibly compelling from a completely self/interior space. Although I thought that the 365 piece was not very moving, and eventually tainted my entire experience through an overwhelming apathy for what I felt to be forced/crocodile tears, I was able to ignore that main hallway enough to take more time with the video works.

I found myself enticed, wanting to watch, wanting to linger, wanting to be an audience member tempted and seduced. It’s not that I had a particular attraction to her at all, but the acts, performances, albiet cliched and occasionally stale, would sometimes add up just enough for me to like _the idea_ behind what was being presented. As a result, I became utterly embarrassed at this want/attraction, and this shyness created a complex situation of unrest within me that I felt compelled to go through in tandem with the works. As a result, I walked through the show with two parallel emotions, one of inherent distrust at playing upon my expectations/desires, and one of genuine intrigue. In this way, I wanted to see more, I wanted to metaphorically pull back the curtain as much as I could to really see what was going on, wanting to see if in fact I was attracted to this woman, or if in fact I was just interesting in the idea of a woman performing in this way. I continued to move around the various black box rooms and sitting down for about two hours in total searching for the idea of that performing woman to materialize fully, to accentuate herself not as passing as a teenager or a young girl, but as a woman of substance, a woman “worth more” than their surface. Perhaps this is central question of the work, “who is the real Laurel?” But the question never became more than a mere thought exercise, and thusly never became interesting, because I was only presented really with one perspective. I had no alternative, or very little personality to respond to, and as a result, the figure on the screen became ultimately one dimensional.

So I became uninterested “romantically” but then became interested emotionally or artistically by the realization that I was not even really looking at the work itself, but looking internally – or within myself – to the idea of a woman performing that way that Laurel does in her work. Truth be told, I think that a lot of the work is aesthetically boring, or also formally one-dimensional. Once I stopped looking at these works with a male gaze – which is what I think Laurel intends at first – but instead through the vision of a person engaged in contemporary ways of creating multiple/alternative identities, I started to check out. The veneer never got past itself. The falsified “tragedy” of a woman using her body for attention/affection never was never actualized since none of the initial elements of the tragedy were ever staged, and in a sense the paradoxical nature of this type of staging/performance (its self imposed horror/sadness as a result of one’s actions) never is fully developed or even put into play. As a result, the work never really became a critique, it only became exposition. Even if one can argue that this “peek into the underworld” is a critique, I was never certain who it was directed at: the expectations of these men (or men in general), the oppressive sexual depiction of women, or the art system that supports “attractive late 20s people” I always remind myself that “showing isn’t enough,” that a certain point action must occur, and that stances/commentary must explicitly come to light at some point in order for the materials of a process to work past their passive participation.

Hi, Corinna:Â

I wanted to say how much I appreciated your article. You addressed a complex issue in a straightforward manner using plainspoken language. Great job. I, too, saw the PS1 solo exhibition, and it was meh. As a pig, I like to look at Nakadate prancing around in her underwear. But as an artist, I find her work tedious. If she wants to make work about her mug and body, then she should make work about her mug and body.Â

However, if she wants to make work about people’s inability to form genuine human connection, I think she would be better served if she began to watch the films of Tsai Ming-liang. He nails it. Â

BrendanÂ

brendanscottcarroll.comÂ

The work is not interesting. She’s not attractive. It’s gimmicky. Why even discuss Laurel Nakadate. There is so much good work out there and so little of it goes through the major gallery system and then people discuss this chic’s work. Lame.Â

“Why even discuss Laurel Nakadate”? She just had a solo exhibition at MoMA PS1, a step above “the major gallery system.” It’s relevant to critique Nakadate’s work because she’s already on her way to being historicized due to her heavy exhibition history. It doesn’t matter whether you like Nakadate’s work; it looks like she’s here to stay.

Hey don’t you remember when art was interesting. Like looking at a rauschenberg in person for the first time and then reading the title and feeling something happen in your brain? Yeah, all this post-academic-hostage-taking just doesn’t do it.Â

What are you even talking about? Who is performing “post-academic-hostage-taking”?Â

I do remember when art was interesting the way you describe, it was when I was in High School.

I looked at Abstract Expressionism for the first time in an art history book, and then later again in person at the National Gallery in DC (I thank my lucky stars that I had the ability to do this as a young artists/academic). I admit it was remarkable, and so memorable that I continue to be inspired by that movement even amidst all of its cultural and political problems. I am able to forgive that work – although Rauschenberg was perhaps the most innocent of that crowd – and still admire it.Â

This process can similarly be applied to Nakadate. To critically engage with work regardless of it being “good” (which is purely a taste, and not a criticism), and to reflect upon the need for higher standards, or else new modes of representation/dialog, is precisely the location in which American AbEx came from. To acknowledge that felt something that you get from of a piece of art as only coming from its aesthetics is to disavow the critical/conceptual value. To do so is an act akin to cultural tourism.

Bitches be hatin’

This is an extremely old thread

Nakadate is an artist who relies on her “looks” as “capital”, which is very different from using “body” as “medium”. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article, yet would love to read more on Wilke and Schneeman, the intellectual and emotional depth in their work which Nakadate lacks. I’ve always found the use of the repulsive male bodies as a background a cheap trick to make her compared youth and sexuality shimmer. The description you’ve used “Juxtaposition of fuckworthy and repulsive” is simply brilliant.

Wilke’s “Starification” and “Snatch Shots and Ray Guns” series aren’t self-portraits. They’re not self-portraits because she’s posing in the guise of others. Holding a ray gun isn’t something I assume she’d do in her spare time. She’s always posing as an other, as another body:Â http://images.artnet.com/images_US/magazine/features/finch/finch1-12-11-1.jpg

From these works, we can’t possibly know anything about what Wilke’s self – or her own body – is like, because her performed image is wrapped up in stereotypes.Â

Clearly we’re going to have to agree to disagree about this one.Â

Regardless, as other commenters have pointed out, the contrast you’ve set up between Wilke and Nakadate isn’t quite so straightforward, considering that many people accused Wilke of using her beauty opportunistically, as they do Nakadate.Â

I agree with you that Nakadate can’t say her looks are off-limits since, as I mentioned in another comment, many of the works hinge on a recognition of her sexual attractiveness to the men she involves in them. However, there’s a certain undertone I’ve heard quite frequently in discussions of Nakadate’s work that I find troubling, which is that the fact that she’s attractive makes the work lazy — the implication being that if she weren’t good looking, it would be more interesting: revealing her body would be a sign of vulnerability instead of narcissism and exhibitionism, etc. etc.Â

I also don’t know if it’s helpful to take one quote from an interview (Nakadate’s “anti-feminist” comment) with a magazine not particularly known for its hard-hitting art criticism, especially since the interviewer was leading the discussion in that direction (by pointing out that “people don’t like that you’re attractive”) and center your entire argument around it. The last paragraph is, in my opinion, particularly misleading: “ Craigslist and the internet are more complicated than the version Nakadate puts forth. It’s a good reason to dislike the work—and it doesn’t resort to dirty tricks like calling someone out for being anti-feminist.”

You’re right; there are plenty of reasons to criticize this body of work that have nothing to do with her looks, and, moreover, we should be able to criticize a female artist who happens to use her body without fear of being called anti-feminist. Unfortunately, the problem here is that Nakadate DOESN’T say that it’s anti-feminist to criticize her work. She says it’s anti-feminist for critics to attack her work BECAUSE SHE IS ATTRACTIVE, which is how the question was posed. Whether or not you want to roll your eyes at that comment or not, as Will seems to, I think it’s important to be specific about using her quote in its proper context and not put words into her mouth.

Clearly we’re going to have to agree to disagree about this one.Â

Regardless, as other commenters have pointed out, the contrast you’ve set up between Wilke and Nakadate isn’t quite so straightforward, considering that many people accused Wilke of using her beauty opportunistically, as they do Nakadate.Â

I agree with you that Nakadate can’t say her looks are off-limits since, as I mentioned in another comment, many of the works hinge on a recognition of her sexual attractiveness to the men she involves in them. However, there’s a certain undertone I’ve heard quite frequently in discussions of Nakadate’s work that I find troubling, which is that the fact that she’s attractive makes the work lazy — the implication being that if she weren’t good looking, it would be more interesting: revealing her body would be a sign of vulnerability instead of narcissism and exhibitionism, etc. etc.Â

I also don’t know if it’s helpful to take one quote from an interview (Nakadate’s “anti-feminist” comment) with a magazine not particularly known for its hard-hitting art criticism, especially since the interviewer was leading the discussion in that direction (by pointing out that “people don’t like that you’re attractive”) and center your entire argument around it. The last paragraph is, in my opinion, particularly misleading: “ Craigslist and the internet are more complicated than the version Nakadate puts forth. It’s a good reason to dislike the work—and it doesn’t resort to dirty tricks like calling someone out for being anti-feminist.”

You’re right; there are plenty of reasons to criticize this body of work that have nothing to do with her looks, and, moreover, we should be able to criticize a female artist who happens to use her body without fear of being called anti-feminist. Unfortunately, the problem here is that Nakadate DOESN’T say that it’s anti-feminist to criticize her work. She says it’s anti-feminist for critics to attack her work BECAUSE SHE IS ATTRACTIVE, which is how the question was posed. Whether or not you want to roll your eyes at that comment or not, as Will seems to, I think it’s important to be specific about using her quote in its proper context and not put words into her mouth.

Clearly we’re going to have to agree to disagree about this one.Â

Regardless, as other commenters have pointed out, the contrast you’ve set up between Wilke and Nakadate isn’t quite so straightforward, considering that many people accused Wilke of using her beauty opportunistically, as they do Nakadate.Â

I agree with you that Nakadate can’t say her looks are off-limits since, as I mentioned in another comment, many of the works hinge on a recognition of her sexual attractiveness to the men she involves in them. However, there’s a certain undertone I’ve heard quite frequently in discussions of Nakadate’s work that I find troubling, which is that the fact that she’s attractive makes the work lazy — the implication being that if she weren’t good looking, it would be more interesting: revealing her body would be a sign of vulnerability instead of narcissism and exhibitionism, etc. etc.Â

I also don’t know if it’s helpful to take one quote from an interview (Nakadate’s “anti-feminist” comment) with a magazine not particularly known for its hard-hitting art criticism, especially since the interviewer was leading the discussion in that direction (by pointing out that “people don’t like that you’re attractive”) and center your entire argument around it. The last paragraph is, in my opinion, particularly misleading: “ Craigslist and the internet are more complicated than the version Nakadate puts forth. It’s a good reason to dislike the work—and it doesn’t resort to dirty tricks like calling someone out for being anti-feminist.”

You’re right; there are plenty of reasons to criticize this body of work that have nothing to do with her looks, and, moreover, we should be able to criticize a female artist who happens to use her body without fear of being called anti-feminist. Unfortunately, the problem here is that Nakadate DOESN’T say that it’s anti-feminist to criticize her work. She says it’s anti-feminist for critics to attack her work BECAUSE SHE IS ATTRACTIVE, which is how the question was posed. Whether or not you want to roll your eyes at that comment or not, as Will seems to, I think it’s important to be specific about using her quote in its proper context and not put words into her mouth.

Hi Rachel,

I’m glad that this comment section has become a forum for various issues that have been fomenting for some time in regards to feminism, reception history, performance, et cetera. If you don’t have an opinion, then you don’t care.

Let me try to parse out the two issues you’ve brought up in your last comment. The first is that if “it’s helpful to take one quote from an interview…and center [my] entire argument around itâ€; the second, is that “Nakadate DOESN’T say that it’s anti-feminist to criticize her work. She says it’s anti-feminist for critics to attack her work BECAUSE SHE IS ATTRACTIVE.â€

In response to the first, this term, anti-feminist, has

touched a lot of nerves. That’s why I quoted from it: it’s a lighting rod for what should, I think, become a fruitful reminder that feminism is still a relevant way of discussing art now. I used the quotation as a platform, not a structural basis for the rest of my argument which ends with a more productive option for discussing Nakadate’s work. I then go on to broach the topic of Nakadate’s overly simple organizational structure for her work, as well as her internet-unaware practice, as a way out of a counterproductive dichotomous

relationship that any discussions focusing on unattractive/attractive, feminist/anti-feminist, or even

exploitative/participatory, will inevitably produce.

As for the latter, which pertains to the paragraph above, nobody’s putting words in Nakadate’s mouth. I brought up Nakadate’s “anti-feminist†statement as a starting point for the rest of the essay. Still, Nakadate herself, it can be argued, put words into the interviewer’s mouth as well. The interviewer brings up that people are “bothered†by Nakadate’s attractiveness, to which she responds with how she’s been

“attacked.†For Nakadate, “bothered†signified other grievances, as is bound to happen because words always signify relationships to other words. Regardless of how flippant this Q&A in NY Mag – which is home to Jerry Saltz – the publication doesn’t always wade in the shallow end of journalism.

Hi Rachel,

I’m glad that this comment section has become a forum for various issues that have been fomenting for some time in regards to feminism, reception history, performance, et cetera. If you don’t have an opinion, then you don’t care.

Let me try to parse out the two issues you’ve brought up in your last comment. The first is that if “it’s helpful to take one quote from an interview…and center [my] entire argument around itâ€; the second, is that “Nakadate DOESN’T say that it’s anti-feminist to criticize her work. She says it’s anti-feminist for critics to attack her work BECAUSE SHE IS ATTRACTIVE.â€

In response to the first, this term, anti-feminist, has

touched a lot of nerves. That’s why I quoted from it: it’s a lighting rod for what should, I think, become a fruitful reminder that feminism is still a relevant way of discussing art now. I used the quotation as a platform, not a structural basis for the rest of my argument which ends with a more productive option for discussing Nakadate’s work. I then go on to broach the topic of Nakadate’s overly simple organizational structure for her work, as well as her internet-unaware practice, as a way out of a counterproductive dichotomous

relationship that any discussions focusing on unattractive/attractive, feminist/anti-feminist, or even

exploitative/participatory, will inevitably produce.

As for the latter, which pertains to the paragraph above, nobody’s putting words in Nakadate’s mouth. I brought up Nakadate’s “anti-feminist†statement as a starting point for the rest of the essay. Still, Nakadate herself, it can be argued, put words into the interviewer’s mouth as well. The interviewer brings up that people are “bothered†by Nakadate’s attractiveness, to which she responds with how she’s been

“attacked.†For Nakadate, “bothered†signified other grievances, as is bound to happen because words always signify relationships to other words. Regardless of how flippant this Q&A in NY Mag – which is home to Jerry Saltz – the publication doesn’t always wade in the shallow end of journalism.

Hi Rachel,

I’m glad that this comment section has become a forum for various issues that have been fomenting for some time in regards to feminism, reception history, performance, et cetera. If you don’t have an opinion, then you don’t care.

Let me try to parse out the two issues you’ve brought up in your last comment. The first is that if “it’s helpful to take one quote from an interview…and center [my] entire argument around itâ€; the second, is that “Nakadate DOESN’T say that it’s anti-feminist to criticize her work. She says it’s anti-feminist for critics to attack her work BECAUSE SHE IS ATTRACTIVE.â€

In response to the first, this term, anti-feminist, has

touched a lot of nerves. That’s why I quoted from it: it’s a lighting rod for what should, I think, become a fruitful reminder that feminism is still a relevant way of discussing art now. I used the quotation as a platform, not a structural basis for the rest of my argument which ends with a more productive option for discussing Nakadate’s work. I then go on to broach the topic of Nakadate’s overly simple organizational structure for her work, as well as her internet-unaware practice, as a way out of a counterproductive dichotomous

relationship that any discussions focusing on unattractive/attractive, feminist/anti-feminist, or even

exploitative/participatory, will inevitably produce.

As for the latter, which pertains to the paragraph above, nobody’s putting words in Nakadate’s mouth. I brought up Nakadate’s “anti-feminist†statement as a starting point for the rest of the essay. Still, Nakadate herself, it can be argued, put words into the interviewer’s mouth as well. The interviewer brings up that people are “bothered†by Nakadate’s attractiveness, to which she responds with how she’s been

“attacked.†For Nakadate, “bothered†signified other grievances, as is bound to happen because words always signify relationships to other words. Regardless of how flippant this Q&A in NY Mag – which is home to Jerry Saltz – the publication doesn’t always wade in the shallow end of journalism.

Actually Will, I think a lot of people have a problem with Laurel using her looks, which is not what Miranda is saying, but is simply what she is pointing out to Laurel.Â

I believe Laurel often has to deal with people saying she is using her looks to get ahead. This a common theme used to undermine women’s successes.Â

And it is interesting for you to bring up your status as being “cool” which no, of course, people couldn’t blame you for using that, because that is typically a masculine trait. Women aren’t usually “cool”, but they can be “glamorous”and are then often shamed or blamed for it. That is another issue I take with this. Men are allowed and even encouraged to use their “male charms” but when a woman does it, she is villainized. But rather that continue to spam the comments section here, if you’d like to continue this convo, feel free to email me annRhirsch at gmail or FB msg me.Â

I mean, it’s cool that you think that, but I just don’t see it – at least not “you’re attractive, and that bothers people”. I’ve never heard that complaint from Sam Taylor-Wood or Dasha Shishkin or Anna Gaskell or any female artist who didn’t have a very clear stake in depicting herself as being both attractive and a target of criticism. Frankly, I had to ask around to get some names for that list right there, because on the whole I have no idea what female artists I don’t personally know look like. Nobody ever thinks to tell me. And I think that’s okay.

It’s an established part of Nakadate’s practice to create situations specifically to show herself as vulnerable and under potential attack, and then to remonstrate against those appearances with an aggressive gesture that proves her self-determination but in no way lessens the threat.

I think that’s exactly what’s happening here. She has fabricated a situation from thin air (people hate attractive women for their attractiveness), has remonstrated against it (by calling them “anti-feminist”), and has done all this in such a way that she still seems to require protection from white knights looking to defend her against the phantom anti-feminists, thus appealing to the same masculine protective urge her Craigslist videos and crying photographs provoke.Â

Maybe that makes this an okay art gesture. I just don’t think it makes the originating statement true.

[Also we can totally talk here.]

I wouldn’t say she’s created a situation “out of thin air,” just as 20+ comments aren’t materializing “out of thin air.” There’s more there than appealing solely to a masculine protective urge; she’s talking to women, too. Â Of “Dancing in the Desert for Britney Spears,” she said she felt Britney needed “some one to watch over her”- granted, that some one was her and Bruce Springsteen, but she’s equally targeting female camaraderie. Â I like that about her. Â

“I wouldn’t say she’s created a situation “out of thin air,””

Why not?

Targeting female camaraderie would, I think, be a legitimately novel thing. I don’t really know anything about that, though, so I guess I just want someone else to elaborate.Â

There’s nothing about thin air, here. Nakadate’s works have touched a nerve and bringing up feminism still touches a nerve, too. Her work is mediocre, but she just had a retrospective at PS1. Nobody’s talking about what her works lack in the mediocrity department; I hope that my suggestions at the end of the essay point to some options.

Comments on this entry are closed.