It’s hard to ignore the glow from The Studio Museum in Harlem’s Artist-In-Residence alumni when visiting the museum. David Hammons, Wangechi Mutu, and Julie Mehretu are just a few of the museum’s now famed past residents, so it’s easy to start thinking about who might be the next star. The current exhibition Primary Sources: Artists in Residence 2011-12, curated by Lauren Haynes, centers around the idea of appropriated source material, a premise that’s basic enough to include work by all three residents, and highlight the best of it. Of all three artists-in-residence—Njideka Akunliyi, Xaviera Simmons, and Meleko Mokgosi—Njideka Akunliyi gets my pick for who might eventually join the ranks of Hammons and Mehretu.

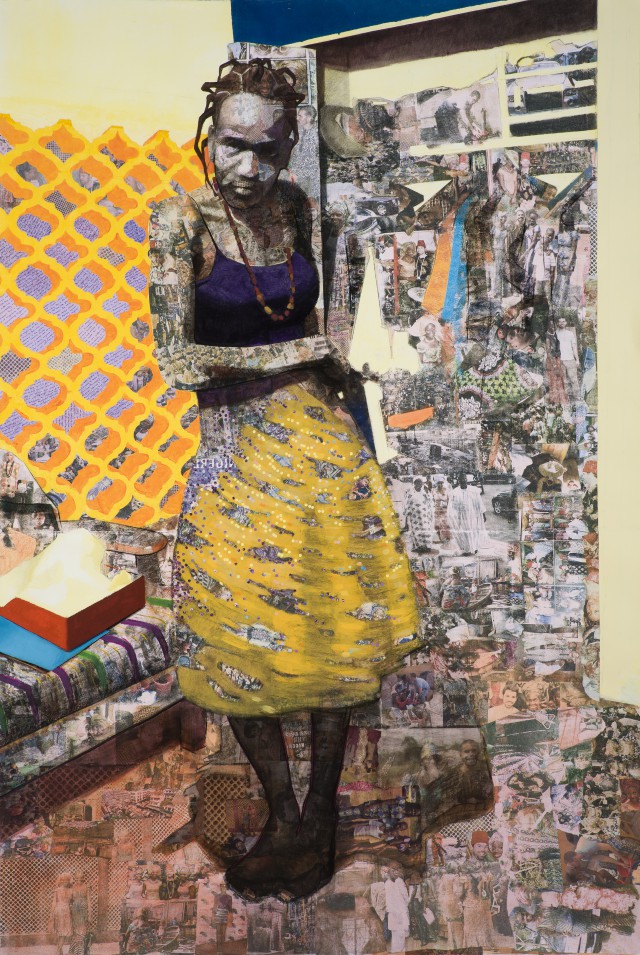

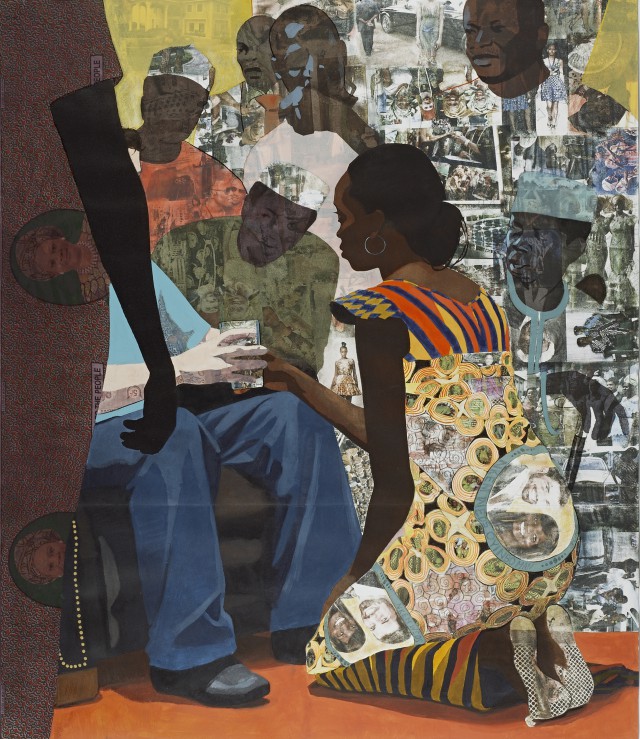

The Nigerian-born Akunliyi creates lush, large-scale works on paper that revel in differences of texture. Upon entering Primary Sources, viewers are confronted with the artist’s Witchdoctor Revisited (2011) and Nwantinti (2012). Both pieces present central figures whose body and surroundings are composed of smaller images that Akunliyi has xylene transferred onto the paper through a printing process. Against backgrounds painted in broad swaths of acrylic interspersed with highly-ornamented elements and outlined in charcoal, the detailed worlds of these smaller, printed panes create a heavily-designed pattern on the skin and floor of the central scene depicted. Pinned to the wall, the varying tactility of the works—at times abraded and rough, and others glittery and smooth—becomes particularly palpable.

Akunliyi’s interest in textile and design brings to mind artists such as Mickalene Thomas and Yinka Shonibare, MBE, while the tension between the foreground and background ornamentation of her works evokes some of the better paintings of residency alumni Kehinde Wiley. But what differentiates Akunliyi from these contemporary references is the vibrancy of the world-within-a-world of the smaller images that compose her collaged figures and designs. Taken from a variety of sources including photographs of the artist herself, Nigerian fashion magazines, postage stamps, and album covers, each small pane captures a bustling world of its own. Whether a celebration of women donning Nigerian geles, stills from Nigerian Idol, or the busy streets of African towns, these smaller images breathe life into the detailed renderings of Akunliyi’s compositions.

The transfer of the printing process elicits a sense of nostalgia in the work, as if the faded images harken back to lingering memories from the past. Akunliyi paints boldly and skillfully—she cites Degas and Vuillard as influences—both before and after transferring these sources. The result is a palimpsest of paint and print that stand out as both alluring from afar and intimate at close range.

The central narrative of Akunliyi’s paintings is the African-born artist’s marriage to a white man and the resulting tension of cross-cultural intimacy. The couple appears in various states of embrace in three of Akunliyi’s five works on view in the exhibition, and their portraits and personal photographs are interspersed throughout the smaller images. Akunliyi describes this tension as one of “questions of allegiance” between her Nigerian cultural heritage and her love for a man of a different upbringing. In this light, the smaller panes evoking Nigerian culture seem to haunt the couple’s drama and reveal the repercussions of “divided loyalties.” It will be good to see if and how Akunliyi continues to focus on this dramatic dynamic. A handful of works highlighting the theme as seen in the current exhibition makes for a thorough investigation; much more than that might be a bit overwrought.

Of the three artists-in-residence, Xaviera Simmons is the most established; she’s had a handful of solo exhibitions throughout the country and was recently included in the Rubell’s 30 Americans exhibition (The younger Akunliyi, by comparison, has yet to have a solo exhibition in New York, though she did quickly sell out a booth at Art Basel.).

Like Akunliyi’s work, textiles and the confluence of cultural references are at play in Simmons’ photographic series Index Three Composition One [Two, Three, and Four] (2012) as well. These four, large-scale, color photographs depict a collection of objects ranging from feathers, skulls, clips, chains, and photos. In the museum’s audio guide, Simmons speaks to the influence of Harlem on the color and collectibles in the work. What is not initially apparent is that the scene of the photographs is the revealing result of an upturned skirt, as the totems pictured in Index Three are tucked tightly against a sitter’s body. Once it is understood that these objects were previously hidden beneath an article of charged clothing, they take on added significance as relics of close personal association and identification.

In the same exhibition as Akunliyi, however, Simmons’ photographs come across as a bit flat, both literally and figuratively. Though striking images in and of themselves, the overlapping items and textures of Index Three are simply less visually appealing when compared to the similar layering processes of Akunliyi’s nearby works on paper.

The most compelling of Simmons’ works is the only sculptural piece in the show, For the Glow Went and the Whole Scene (2012). The piece consists of black wooden planks arranged into a mast-like configuration with poetic lines painted across their surface in block white letters. The lines on each plank don’t seem to have any immediate relationship to each other, and include opaque yet intriguing phrases such as “THE INTENSE SATURATED COLOR OF” and “LONG RAMBLING STORIES ABOUT THE SEA.” In attempting to figure out how the lines related, I found myself circling the work, reading one line at a time. Though certainly dizzying, this circling process particularly resonated when the simile in the seventh line read “LOOKING LIKE A WOLF CIRCLING A BITCH IN HEAT.” When the poetics and process of viewing Simmons’ work aligns in ways such as this, the artist is at her best.

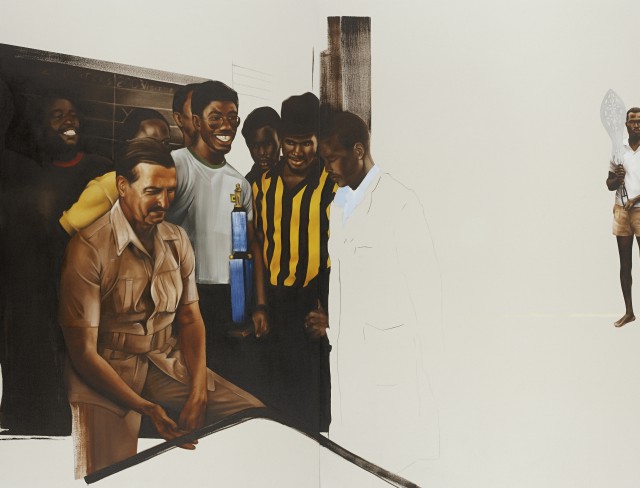

The third artist-in-residence, Botswana-born Meleko Mokgosi, presented a series of paintings similar to those that recently won him the Hammer Museum’s $100,000 award given out to one artist in the museum’s Made in L.A. biennial (though not without a bit of contention over the way in which the prize was awarded). Mokgosi’s two nearly mural sized, multi-panel paintings Pax Kaffraria: Terra Nullius (2009-12) show deftly painted portraits of African and white figures that hover in difficult to discern relationships over wide expanses of negative canvas space. The paintings mix fiction and fact as cultural figures and source images are interlaced in imaginary dynamics.

In contrast to the sprawling beauty of these paintings, Mokgosi also exhibited his text-based Wall of Casbah (2010-12) series. The five works on view here consist of text from museum wall labels, including those describing sketches of the redesign of Algiers by Le Corbusier. Mokgosi blew up the scale of these wall labels, printed them onto linen, and annotated them incisively in charcoal. Mokgosi defines, crosses out, brackets, and draws arrows over the initial text, deconstructing and implicating the narratives and elisions of each label in the process. Some of the more biting lines from Mokgosi’s rambling, yet keen, curatorial critique include: “what a magically natural and pointless description” and “here the wall labels reframe the text towards a narrative that fulfills the deeds of so-called historical considerations of the city.”

We could all do better to bring a similarly critical eye like the one Mokgosi aestheticizes in these works to the texts and narratives that structure our art-viewing experience. That being said, the two series on view from Mokgosi in Primary Sources present two disjointed sides—of alluring aesthetics and trenchant critique—that are rather hard to reconcile in the space of a single, small exhibition of his art.

Which brings me back to what makes Akunliyi’s work the principal success of Primary Sources. At just 28 years old, Akunliyi seems to have already fleshed out a practice that recasts a disparate array of sources and materials into a cohesive aesthetic sensibility. Akunliyi’s work loses much of its tactility and detailed nuance in reproduction, so the exhibition provides its own direct evidence—or primary source—of her budding potential. There will more than likely be many more exhibitions of Akunliyi’s art, but Primary Sources (closing this weekend, on October 21) is an early opportunity that should not be missed.

{ 1 comment }

“At just 28 years old, Akunliyi seems to have already fleshed out a practice that recasts a disparate array of sources and materials into a cohesive aesthetic sensibility.”

Amazing article.

Comments on this entry are closed.