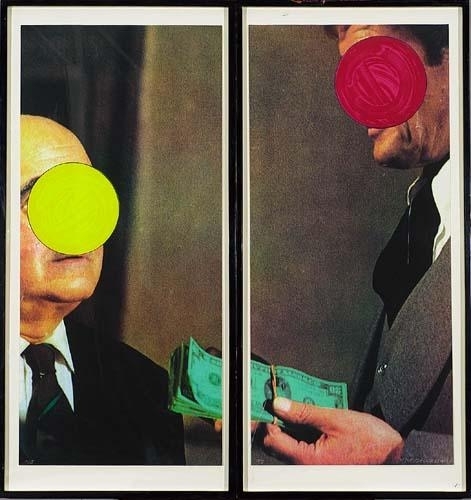

Over Facebook, I asked an informal question about who pays artists. I wasn’t surprised by the results. Many artists, including those still in school, tend to pay other artists, actors, and writers who’ve assisted with the production of a work. Even those with limited means tend to exchange work, materials, or other barterable goods. Contrast this with the fact that when a non-profit or museum pays artists and their assistants, it seems like a rare, almost noble deed.

There are expectations in the arts, as with any other industry, to value the time, effort, and labor of others. It’s just harder to figure out how to go after fair payment by arts institutions when the promise—of even a meager stipend—remains an uncommon practice.

The answer is certainly not to be found with major museums and non-profits. Formed in 2008, the artist advocacy group W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) has continually put pressure on non-profit institutions to pay stipends to artists, both to cover the materials and time put into producing a work. Art (and curating and writing) cannot be treated as a hobbyist pursuit. As such, payment should be de rigeuer; instead it’s about as common as taking the Z train.

This isn’t to say that non-profits don’t pay at all. More often than not, it’s the larger ones that end up coming under fire for non- or under-payment to artists and those who assist in the production of a work—Performa, Creative Time, or the Whitney Museum, for instance. Just a few weeks ago, Performa announced an unpaid residency for writers who will contribute “roughly four to six articles or features” to Performa Magazine. Earlier this year, one group of performers resorted to Kickstarter so they could fund their 2014 Whitney Biennial performance, a world premiere opera by the late Robert Ashley. Whatever works, I guess.

Contrast these situations with what goes on in the city’s smaller non-profits. Unlike those larger institutions with a solid mix of funding sources, from a variety of corporate, foundation, and individual supporters, these non-profits depend on city, state, and federal funding. When it’s the city that’s allocating funds, just a few thousand dollars requires artist-stipends to be awarded. This accounts for the strange fact that smaller non-profits like NURTUREart, SmackMellon, or Flux Factory, with just a tenth of the Whitney’s operating budget, end up giving some form of a stipend.

These types of organizations are usually referred to as “artist-centric,” and with good reason. It’s not just that they tend to pay artists, it’s that they participate in a system of value common to all artists. Many younger artists, including those without gallery representation, do tend to pay the actors and volunteers they hire. Even when the money isn’t there, the system of bartering and trading in supplies, meals, and other resources is a system that’s ingrained in how artists make work. Value is always given, despite the lack of financial resources.

Perhaps there’s some element of forgetfulness at the top of the non-profit ranks. These institutions came out of this value system, but it’s been long pushed aside. In favor of just any old artist project, the need is for spectacular, engaging works. Often, the idea is to go big or go home.

Just look at the Whitney Biennial performance funded on Kickstarter. The artists have raised over $55,000, an amount that would pay a nice salary at a small non-profit. A grand, world premiere opera by the late and great Robert Ashley fits in line with the new rule for museums to go bigger—even if they can’t pay for it. Artists are short-changed while money gets lavished on executive salaries and capital campaigns.

I don’t want to grumble, I want to see a change. Those of us in the arts have lived with the stigma of being poor long enough. And part of the problem is this substantial gap between the value offered to artists at the level of small and large non-profits. A better approach to funding would require across-the-board standards—it shouldn’t be just city, state, and federal grants that require artist-stipends. All forms of giving, from corporate to foundations, can require it, too.

That’s just one solution. What really needs to happen is to remember where we came from in the first place, out of a system that values everyone’s efforts.

{ 4 comments }

Do you think that this might have to do more with how distant the larger non-profits become from their revenue/grant streams? Most of those smaller non profits spend majority of their year grant writing – many times for multiple small grants to help funnel in funding. So they have to make a conscious effort to make every dollar count, give back to the community etc. The annual reports a small non profit or an artist has to write for money they receive needs to show reason for every dollar spent. I really wonder if that same kind of scrutiny exists when the board of the Whitney, or some other large organization, is making decisions.

Another thing to consider, the small organizations may just be fiscally sponsored, not board run non-profits. The non profit structure is really complicated as to how it can allocate money based on the decisions of the powers that be (board, finance dept. etc) With fiscal sponsorship I feel like those that run the organizations get to put money right where they want to.

I think the most important thing we can do is have greater transparency with the grant-funding process. I wouldn’t be surprised that due to the reliance on grant writing more than individual, corporate, and foundation donations that smaller non-profits work the way you mention.

But I wouldn’t say that fiscal sponsorship is necessarily a boon for organizations (AFC is fiscally sponsored). Regardless of the size of one’s organization, I suppose that it might be easier to run with a smaller board and smaller staff—just because it’s easier to get a smaller number of people on the same page.

At that point it unfortunately almost comes down to the institutional politics in play. Where corners can be cut, they are. Too many artists are still unfortunately wooed with the promise of exposure or a resume line, so why pay?

Plus smaller non profits aren’t swayed by the needs of the corporate funds or other foundation’s agendas they partner with. Unfortunately a lot of time the people left to the bottom of the totem pole are artists and I am really glad you brought this up!

With all due respect there is value in having a look at what happens outside your borders too. In Canada most institutions large and small pay a set artists fee which is mandated by their funders, usually governmental including municipal, provincial and federal. This is because back in the 60’s and 70’s (and ongoing) a group of artist organized into CARFAC: Canadian Artists Representation Le Front des Artists Canadien: http://www.carfac.ca/

They are currently working for Artists Resale Rights in Canada.

The notable and lamentable exception to paying artist fees is the largest institution, the National Gallery of Canada, in an ongoing battle. It’s complicated apparently, but not really.

http://www.canadianart.ca/news/2013/11/26/carfac-national-gallery-supreme-court-over-artist-fees/

Yes, Artists are driven by forces that go beyond the pragmatic, but we still need to eat, pay rent and maybe send our kids to school.

Comments on this entry are closed.