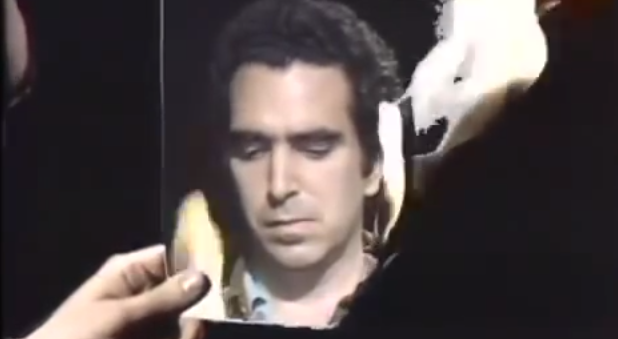

Still from Peter Campus, “Three Transitions,” 1973. His videos were once distributed by Castelli-Sonnabend Tapes and Films.

Over the years, we’ve come up with any number of ways to package editions for collectors used to having precious objects around. With our minds so continually set on making art fit for sale, we tend to forget there’s other types of collectors out there, who aren’t interested in one-of-a-kind living room ornaments. That’s where the Castelli-Sonnabend Tapes and Films (CSTF) company comes in; despite its ties to the Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend galleries, traditional collectors weren’t courted there. If there’s just one lesson to be dragged out of CSTF’s history, it’s that art markets can be fostered at more levels than just the top.

An independent subsidiary of the Leo Castelli and Sonnabend galleries, CSTF ran an ambitious video and film sales and distribution platform from 1974 – 1985. Sales were poor, and it’s a miracle the company existed as long as it did. While CSTF failed to garner a quick, strong profit from sales and rentals, there was another, albeit slower paced business model in place that did succeed. This model wasn’t ruled by sales, but influence.

Here’s how CSTF worked: Rather than going after traditional art collectors, the gallery sent out catalogs listing the name of works available for rental or purchase to universities, museums, and art schools. For the most part, the artists came from Castelli and Sonnabend’s pre-existing roster (Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, and Lawrence Weiner); the catalog would expand to include over 35 artists, including experimental video and film artists like Peter Campus, Juan Downey, and Hermine Freed. Prices ranged from $30 for rental to $300 for purchase; throughout the length of the distribution program, these prices rarely changed. (Even into the 1990s, after the formal close of Castelli’s rental and sales program, prices remained consistent; you could still rent Bruce Nauman’s “Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling With Changing Rhythms” for $30.00.)

As you can imagine, those prices didn’t rake in much of a profit. As of 1983, CSTF accounted for one percent of all the Leo Castelli Gallery’s sales revenue. So sales weren’t the company’s priority. Even someone like Vito Acconci never sold a video to anyone outside of a museum, university, or library during the decade his work was represented by CSTF.

Collectors at the time weren’t ready to collect video and film—but the artists and administrators running academic and museum programs were. And given the budgets of these programs, this type of media couldn’t have been more appealing. Looking through the CSTF financial records, the first record to come up is Guelph University, which is located just outside of Toronto, Canada. Other early rentals and purchases came by way of schools like the University of Southern California, Aquinas College, Virginia Commonwealth, Smith College, the University of Pittsburgh, Oberlin College, and the University of Oklahoma. You get the picture. Individual collectors do show up in the record from time-to-time, though; Stanley Grinstein, an avid collector as well as founder of the Gemini G.E.L. print company, purchased Nancy Holt and Richard Serra’s “Boomerang” in 1975.

Video was planted all around North America by getting outside of the gallery-as-storefront model. You didn’t need to stop into the New York gallery, or even be in the know enough to give the gallery a call—CSTF came to you. It wasn’t just anyone or everyone they targeted, just those who, in tech-speak, we’d refer to as “the innovators.” An entire generation of students, scholars, and curators emerging from these institutions in the 1970s and 1980s had access to this work. As such, the the film and video “brand” entered new markets, outside of Leo Castelli Gallery’s collector base. The rest is history.

Research for this essay was performed at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

{ 1 comment }

The rest is history… and also the present. Thanks to the author Corinna Kirsch for illuminating the important work of the CSTF and the origins of the distribution system for uneditioned video art in America. It is worth noting that the system set in place by the CSTF is not a historical outlier, but a robust and ongoing facet of the economic landscape of media art. With great foresight, CSTF recognized that the non-profit model might better support video art distribution in the long term. After closing in 1985, CSTF donated the bulk of their master tapes to the Video Data Bank in Chicago and Electronic Arts Intermix in New York. These organizations, along with a small number of other video art distributors around the world, took up the mantle of preservation and access, continuing to serve scholars, educators and curators, and to “plant” video outside the system of galleries and private collectors.

Each of these non-profit organizations continues to work to bridge the gap between the aesthetic and commercial realms of video art. Their videos are available to educational customers including universities, festivals, museums, and community media centers worldwide. It is particularly notable that these organizations charge fees that are nearly identical to those charged by CSTF for the same work in 1974. Contemporary non-profit distributors work to promote accessibility, and maintain a cost model that allows access to rare media work for those outside the economic art centers. Proceeds from sales and rentals go to partially support the archive and preservation activities of the collections, while also providing the artists’ with compensation for the continuation of their practice.

Comments on this entry are closed.