All Photographs: Christian Grattan

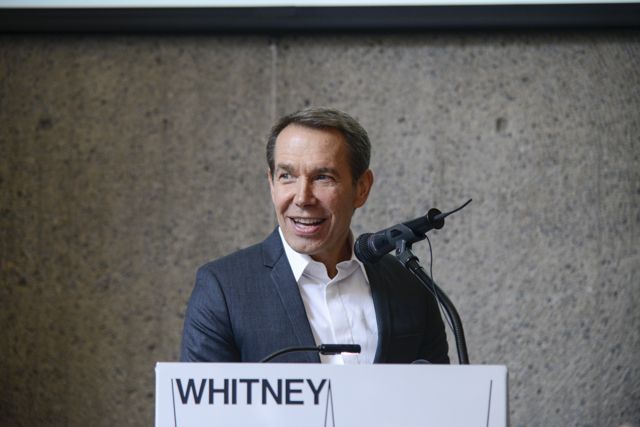

Art is a “platform for the future,” Jeff Koons announced at yesterday’s press conference at the Whitney. What that means is anyone’s guess, but he followed that up by explaining that he’s 59 and hopes to be making art for at least another three decades. In short, while this may be his first New York retrospective, it won’t be his last. The retrospective opens this Friday, June 27th, and runs until October 19th, and will include work from 1978 through 2014.

Spanning all but the fifth floor of the museum, and including more than 150 works in all shapes in sizes, its not hard to see what a mammoth undertaking the show must have been for the museum. The insurance costs alone could have been crippling. Precedent, too, has not been good. In 1996, the Guggenheim scheduled and rescheduled a retrospective with the artist, only to abandon the idea. The cost of fabricating pieces in the “Celebration” series, which is defined by large scale stainless steel and plastics, was cited as one reason for the cancellation. Those issues are reportedly still an issue, though no longer insurmountable.

And so, perhaps it’s not too surprising that the Whitney staff all proudly bore incredulous grins yesterday as they promoted the show—as if launching the show was an achievement unimaginable even a few years ago. Whitney Director Adam Weinberg spoke of Koons’s “commitment to perfection,” his “exacting” mind, and his obsession with his artwork. Perhaps more meaningfully, Donna De Salvo, the Museum’s chief curator, spoke of the need for a more cohesive narrative for his work, saying, “The ubiquitous nature of the work does not mean that we know it.” In an effort to address the need for a more complete perspective, show curator Scott Rothkopf told audiences of his interest in assembling key works from each series to expose the diversity of ideas and approaches Koons brought to the table.

Koons’s work is known to be divisive, so there are many likely to take issue with that perspective. Readers can come to their own conclusions by clicking through our preview slideshow and visiting the show at the Whitney once it opens this Friday.

Taking pictures of “DR Dunkenstein,” 1982, in which the now retired basketball star Darrell Griffith holds a steaming, severed basketball.

“Three Ball Equilibrium Tank,” 1985. Anyone else bothered by the fact that these balls are slightly off center?

Marina Galperina of Animal New York reflected in “Inflatable Flowers (Short Pink, Tall Purple),” 1979.

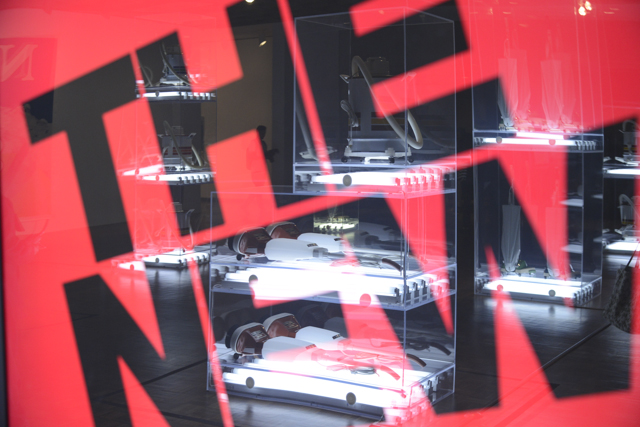

“New Hoover Convertibles,” 1981-87, reflected in “The New,” 1980. These works were all about newness of commercial products, hence the neon hoover vacuums. Ironically, these pieces are now mostly over 30 years old. Planned commentary on obsolescence? The curator seems to think so. “The specimens in these antiseptic chambers have inevitably grown dated, suggesting that the eternal and inexorable quest for the ‘new and improved’ in both art and commerce is inherently shadowed by the threat of obsolescence,” Rothkopf wrote.

“Made in Heaven,” 1989, is just one in a series of pornographic images of Koons and his ex-wife, Ilona Staller. This is the first image that you see on the third floor once exiting the elevators; the other, more graphic images are tucked away. Those with small children, take haste.

The lineup in this room included a ton of Koons’s all-star ceramics, like “Michael Jackson and Bubbles,” 1988, as well as less popular works like “Bear and Policeman,” 1988, and “Woman in Tub,” 1988. This is some of his most kitsch work to date.

String of Puppies,” 1988. Koons ran into some copyright issues with this one, in which the United States Court of Appeals found Koons liable for for copyright infringement.

“Split-Rocker,” 1999. Behind this, “Kangaroo,” 1999. The work’s playful content, using and referencing products specifically made for children, stands in contrast to the sex-based imagery of the “Made in Heaven” series. The two sit only feet away from each other in the exhibition space.

One of Koons’s most iconic works, “Balloon Dog (Gold),” 1994-2000. It sat in a room on the fourth floor with other large works, which appropriately had a dwarfing effect on the visitors. The sculpture (or at least the orange version of it) went for $58.4 million at Sotheby’s in November 2013, by the way.

A security guard stands alert next to“Hulk (organ),” 2004-2014. This is a functional organ, although visitors are not allowed to touch it.

A room of Koons’s newer work. He uses his trademark balloon effect on an image of the Venus. “Balloon Venus” takes the ballooned form, which Koons previously used to talk about contemporary larger-than-life pop, and puts it in the context of the timeless Venus.

{ 1 comment }

Simply put, Koons work is infantilizing. It generates no new thinking or

exploration of ideas or even wonderment at the deployment of a concept, the unique properties of materials, the obsessive quality of a making process. It just takes us up close an personal with a lot of what is vapid and tedious and consistently celebrity-oriented in our culture.

What is the worth of looking at work like this–especially more than once? The responses it encourages and makes space for is very much the typical mouth agape and head tilted to the side curiosity at bright, shiny objects that have the sheen of coalesced money/time/energy without any of the traces of the labor. This is not a curiosity that leads to thinking, but rather to schadenfreude, or worse to the adoption of these types of mirroring strategies, as if to say our own vapidness is a surefire conceit that will attract attention.

We don’t need a retrospective. We need a bonfire. We need to turn our backs on work that asks us to smile and nod and accept the emptiness of merely acting as fan club, passive audience, witnesses. Please, we may not deserve better than this awfulness, but we NEED it.

Comments on this entry are closed.