We in the States find ourselves on a steep learning curve when it comes to knowing the basic histories of Middle Eastern and African countries. We’re not a nation known for looking far beyond our front door. But the mounting political instability of these regions is changing that. We want to know more.

It’s unfortunate, then, that the lessons I got out of Here and Elsewhere, the New Museum’s current exhibition of art from the Arab World, weren’t the least bit challenging. We’re told contemporary art should look like other contemporary art and exhibitions, and that if that art is political, it should reference past events. That’s not much of a lesson plan.

Our textbook, as such, leads with the concept of “globalism.” Though you might not recognize the names of the approximately 45 artists in this exhibition who take up all floors of the museum (excluding, perhaps, Yto Barrada, and now, Khaled Jarrar, due to his well-publicized detainment in Palestine), the work will seem familiar to anyone who ever heads out to art fairs, biennials, and blue-chip galleries. Most of it looks like it’s for sale.

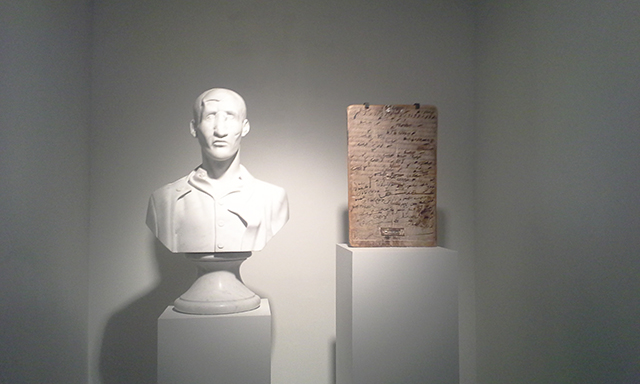

That generalized “new art” gloss includes everyday objects reconstructed into strange sculptures (Rheims Alkadhi’s crumpled rubber tube, or Hassan Sharif’s plastic sandal piles), colorful, textured abstract paintings (Etel Adnan’s AbEx monochromes also featured in the 2014 Whitney Biennial), re-stagings of historical events (Marwa Arsanios’s “Have You Ever Killed a Bear?”), or invisible histories. (Kader Attia’s “Repair, Culture’s Agency” juxtaposes a “writing board” common to children in North Africa with a bust of a wounded French soldier from World War I whose face has undergone surgery. Both have been repaired.)

These methods are common in contemporary art can usually be traced to an established market. Contemporary art has become Starbucks-predictable, with nearly the same ingredients to be found at any location worldwide, reaping returns with the same formula. For what it’s worth, a work from Attia’s “Repair” series was listed by Galleria Continua at Art Basel for 95,000 pounds. And that’s not a surprise. It’s exactly the type of given that it looks like the type of contemporary art you’d find at an art fair, engaging with by-now familiar art theory on indexicality and trace. In other words, it’s not breaking any new ground.

Naturally, even the exhibition’s design mirrors these market-driven events. Taking up all floors of the New Museum, I had to visit the museum twice, and stayed over three hours just to spend enough time with each work in the exhibition. Watching the videos takes an entire trip on its own. The exhibition’s biggest flaw is, indeed, the show’s scale: most visitors aren’t going to return multiple times for an intro to art in the Arab World. Museums do not need to include hundreds of artworks in a single exhibition—I was drooping with the same type of exhaustion I feel after an art fair. (Please, let’s stop this spectacle of too much art in one place at the same time.)

That recognizable brand of global contemporary art shouldn’t be a shock in an exhibition of artists who no longer live in their home countries. A handful have been schooled in Europe or abroad (or currently live in places like Berlin and Amsterdam); they have the luxury to relocate, and be an artist. (I’ve made a Google Doc listing all their home countries and current locations.)

Here and Elsewhere shows what we already know to be true about the the art world; no matter where you’re from, you’re allowed entrance to the art world if you have access to the right networks. It makes sense, then, that Here and Elsewhere would not try to show all types of contemporary art being produced in the Middle East—that would be an impossible task, especially given the current state of unrest in many Arab World countries.

Not that that current unrest, or our country’s involvement with it, gets paid much attention. The second lesson of Here and Elsewhere is that politics gets a go-ahead when it references the past. The prevailing mood of the exhibitionwas one of neverending sorrow; like postwar German and Austrian artists before them, the artworks made by Arabian artists appears to suffer from trauma regarding atrocities of the recent past. And there is no escape from these ghosts.

Even though this may be a familiar trope in contemporary art, it was a good counterpoint to have around to the more familiar-looking work in the exhibition. I didn’t mind it. These particular “ghosts” do set apart these artists from their global contemporary art counterparts, and for that alone, Here and Elsewhere has some enlightening moments. Because no matter what, even in peacetime, or when you’re away from your home country, war still looms in your mind.

As such, works did tend to focus on former political events of the past. The Lebanese Civil War (1975 – 1990) recurs a handful of times. Lamia Joreige’s “Objects of War” series of interviews asks interviewees about their experiences during the war; Marwan Rechmaoui’s “Spectre (The Yacoubian Building, Beirut),” replicates the artist’s former apartment building in Beirut, which had to be evacuated in 2006 during the military conflict with Israel. Other recent events, like the U.S. presence in Iraq, is merely hinted at. Jamal Penjweny’s “Saddam is Here” (2010) shows Iraqi residents holding a picture of the dictator in front of their own. Other events of recent import, both globally and within the Middle East—namely, the events of the Arab Spring or even more recent, the Syrian genocide—are barely, if ever, mentioned. (Khaled Jarrar’s full-length film documenting Palestinians crossing the border into Israel remains an exception to highlighting very-current political problems.)

Installation view of Wafa Hourani, “Qalandia 2087,” 2009.

The best works in the exhibition didn’t follow the textbook. Rather than looking back with regret, they looked towards the future of the Arab World, and in effect, its art-making practices.

For example, Wafa Hourani’s gorgeous “Future Cities” series shows several different kitchen-table-size dioramas concerned with “Qalandia 2087” (2009). Each diorama envisions a different future for Qalandia, a Palestinian camp on the West Bank, assuming a number of different scenarios—Israel wresting control of the area, a shanty real-estate boom, and the like. Made out of glitter, paper, mirrors, toys, and other easy-to-find objects, these constructed cities seem like an innocent, almost childlike wish for a future that may never be. The desire for change is there, though the bric-a-brac materials end up giving off an impression of powerlessness.

Another future-mindedwork, Maha Maamoun’s haunting video “2026” (2010) looks like French filmmaker Chris Marker’s La Jetée, but adapted for a near-future dystopia in the Middle East. “People have been wiped out of existence, but the Egyptian Museum in the distance still exists to preserve what was,” the narrator (who looks nearly exactly like the narratorin La Jetée, “The Man” ) states. He then describes an Egypt where holographic screens create a sense of normalcy for the elites, while the impoverished parts of the “real” city crumble. It’s a perfect observation for what’s happening in the Middle East—and elsewhere around the globe—that the first-class is going more high-tech, while the rest of the world seems to be worse off than ever.

It’s these works with an eye towards the future, and the unknown, that I find most promising; though the models sometimes look familiar, they’re headed towards uncharted territory. What will their textbook look like, if they even need one?

Comments on this entry are closed.