Most of the promotional materials and press for Yoko Ono: One Woman Show begin with the same story: in 1971, she advertised her unauthorized “one woman show” at “The Museum of Modern [F]art”. Outside MoMA, Ono posted signs describing the exhibition: she had released flies in the sculpture garden and viewers were encouraged to follow them as they dispersed throughout the city.

It’s one of those countless Yoko Ono stories that makes her a legend to some of us and an oddity to the mainstream. Almost half a century later, MoMA attempts to demystify Ono’s practice with an exhibition that focuses on the decade leading up to that first, unofficial “one woman show”.

That attempt at demystification sometimes seems like a stalemate, as Ono’s work during that period was so often itself an attack on institutional culture of display and traditional considerations of objecthood. The resulting exhibition can at times feel like a stagnating, polite tension akin to what I imagine a disputed border would be like after a cease fire—with Yoko Ono’s militantly enigmatic practice mediated by bland curatorial interventions that attempt to make it more digestible to the general public. Think institutional wall text earnestly explaining the importance of an absurdist film of butts next to the artist’s own plinths parodying museum display.

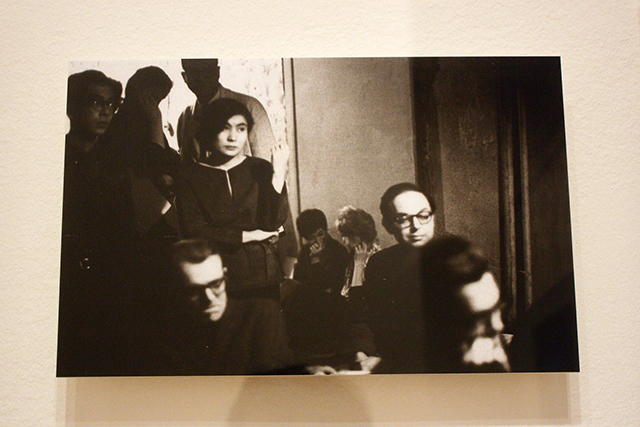

Which isn’t to say that the work itself is bad or boring—Ono’s practice during the 1960s is full of nuanced surprises, and the show’s layout, which is loosely organized around her back-and-forth globe-hopping from Japan to England to New York is itself a compelling narrative. From the listening room with Ono’s music to photos of the happenings she threw at her Chambers Street loft, it’s great to be reminded that Ono was punk as fuck before punk even existed.

But the museum’s presentation here can sometimes take the teeth out of the work. Interactive objects that once served a function—even if that function was non-objective—are displayed like ancient artifacts, neutered of their potential to facilitate an experience and given meaning solely by didactic text. Just as bad, many pieces that already feature the artist’s own text are accompanied by over-explained and overpowering MoMA commentary designed to sell a viewer on its importance. It never helps. We don’t really need this much didactic text telling us that something is supposed to be weird and then explaining why.

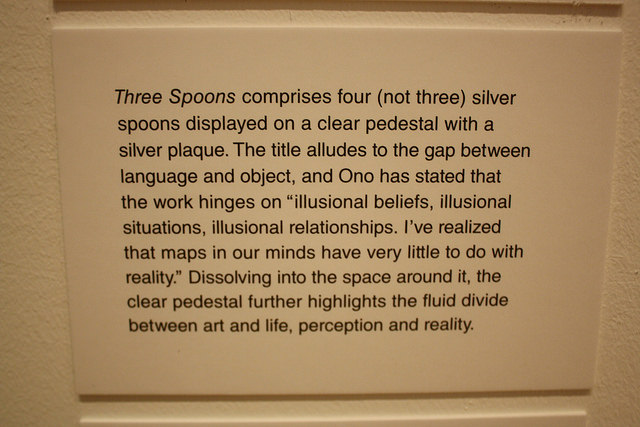

Ono’s 1967 piece Three Spoons is definitely one of the victims of over-curation. The piece consists of a plexiglass vitrine with a plaque. Inside, four spoons are displayed with the title Three Spoons. It’s a somewhat goofy statement about the disconnect between language and the world it describes. As a standalone piece, it could also be seen as an attack on the ability of the museum to remove any sense of wonder or joy from the act of art viewing. I was reminded me of the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens in South Florida: there, (in what I was told is a Japanese tradition) plants and garden features aren’t labelled because one should be thinking about the experience of the thing itself rather than the words used to describe it. Here though, we’re treated to a lengthy explanation that Ono’s labelling was deliberately wrong. It’s so odd to read a piece of didactic text about an artwork that’s itself partially a subversion of labelling.

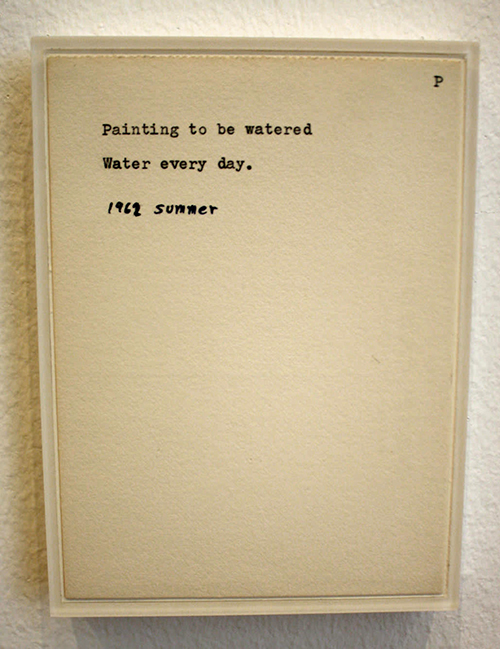

The real highlight, though, is the original typescript with hand-written notations for the book Grapefruit, Ono’s 1964 fluxus masterpiece. The book is comprised of instructions for the reader that largely deal with constructing “paintings”. It’s odd to see these pages as precious objects, because part of the appeal of Grapefruit has always been its association with an utter lack of objecthood—both in content and the relatively ubiquitous paperback reprints, transcriptions, and copies of the book that exist. The artwork described in the instructions is created equally by Ono and the imagination of the reader and often involves picturing the “paintings” being destroyed. This tension between original and copy is perhaps best exemplified in Painting to Exist Only When it’s Copied or Photographed: “Let people copy or photograph your paintings. Destroy the originals.”

So it feels like a breach of contract, or some type of betrayal that Ono physically created some of the instruction paintings for this show. It’s small consolation that they’re hung in another room, away from the original text. On top of feeling like a conceptual violation of the original, they are also a thousand times less visually interesting than the “paintings” I’d always imagined. These drab grey curtains of canvas—even the one with a plant poking through—seem dead rather than performative.

Contrast how boring this image is:

With the experience of reading Painting to Be Constructed in your Head:

Go on transforming a square canvas

in your head until it becomes a

circle. Pick out any shape in the

process and pin up or place on the

canvas an object, a smell, a sound

or a colour that came to your mind

in association with the shape.

Similarly stripping Ono’s work of its vital potential for participation, most pieces that were originally intended to be touched are frustratingly displayed behind glass. That’s totally understandable, given their age and value. What I can’t understand is why the Grapefruit paintings were extraneously produced for the exhibition, but that it didn’t occur to the artist or curator to fabricate less precious versions of works that depend on tactile interaction. That’s most of an issue with Touch Poem, a handmade book of different textures that was intended in the 1960s to be “read” by running one’s fingers across them. Here, it’s in a vitrine and viewers are invited to flip through photos of it on a touch screen. It’s literally the dumbest curatorial solution to a display problem I’ve ever encountered—it completely misses the point of the piece.

A Box of Smile is also tucked away behind plexiglass. The piece is a wooden box with its title printed on the lid. When they’re opened, there’s just a mirror inside. Fabricating more of these for visitors to encounter would have been great and inexpensive. Instead, the originals are displayed in weird windows with doors that slide up. And instead of allowing the super-self-explanatory Box of Smile to be a pleasant surprise, they’re accompanied by paragraphs of wall text that command the viewer to open the window, see the mirror, and understand that he or she is supposed to smile at their own reflection. It was the art-viewing equivalent of an uptight parent taking their children to a park and lecturing them on the importance of fun.

These attempts at mediating interactions with Yoko Ono’s work are disasterous. The best experiences I had with the exhibition tended to be based on coincidence or accident. In the central gallery, beneath a skylight, there’s a 1967 piece entitled Glass Keys to Open the Sky consisting of four glass keys in a transparent box. Next to it, there’s a piece from 1961 that is essentially a vending machine that once dispensed pieces of paper with the word “Sky” written on them. Other than being disappointed that the vending machine wasn’t functional—yet another object transposed from the realm of artwork to artifact—I didn’t give much thought to these pieces at first. But after ascending To See the Sky, a frighteningly rickety spiral staircase Ono installed specifically for this exhibition, the pieces took on a new, ironic profundity.

The 1960’s pieces absurdly proposed a deed or key to the sky—suggesting that one needed to be reminded of it, or given ownership of a seemingly non-commodifiable expanse. Ono might have intended To See the Sky as a generous gesture towards the viewer; an opportunity gifted to take in an exterior view from an otherwise windowless space. But when one reaches the top of the staircase, the vista is dominated by the impossibly tall 432 Park Ave looming over Midtown. Perhaps no other piece of contemporary architecture is as semiotically loaded as a lightening rod for discourse over the very literal class stratification plaguing the city. Rather than seeking out a rare patch of open sky, I found myself imagining that Ono’s Glass Keys to Open the Sky unlocked a $100 million penthouse/investment property towerng above the cloud line—the idea of sky as capital made real by steel, concrete, and—yes, floor-to-ceiling glass.This might have been a deliberate, brilliant statement, a coincidence born out of naïve oblivity, or a happy combination of the two. Part of the enduring allure of Yoko Ono is that one is never quite sure.

To See the Sky is supposed to afford an opportunity to cloud-gaze. Instead, the skylight is totally overpowered by uber-luxury 432 Park Ave, the Western Hemisphere’s tallest residential building.

Overall though, it’s always a dissapointment to see the work of a great artist muted by crappy curation. One Woman Show represents yet another let-down from MoMA’s chief curator Klaus Biesenbach, who organized the exhibition along with Christophe Cherix and MoMA curatorial assistant Francesca Wilmott. Ono is definitely a moving target, but the curators were way off-the-mark. Yoko Ono’s greatest successes were about finding earnest moments in absurd celebrations of the mundane or a dissolution of hierarchies of value. MoMA seemed bent on proving to us that these gestures can be reduced to a forced aura of preciousness surrounding physical minutiae.

This problem points to a larger quandary endemic to the museum. Part of MoMA’s mission is “helping the widest possible audience understand and enjoy modern and contemporary art”. But much of the 20th Century’s cultural production was characterized by a desire to not be understood—to break with the cruel logic of the grand atrocities of its early decades and the quiet ones that played out subsequently. Enjoying Ono’s work in particular is dependent upon allowing oneself to surrender instant comprehension—to trust her temporarily—to dismiss the impulse to view the absurd and the sincere in binary terms. Seeing One Woman Show, I found myself wishing that the only text in the exhibition had been Ono’s, that the only narratives had been her films, and that her work had been treated as something that still has the potential for a phenomenological appreciation rather than illustrations for an art history lesson.

{ 1 comment }

ono is and has always been a total hack, the biggest joke jon lennon ever pushed upon the american people

Comments on this entry are closed.