Trying to understand blockchain technology is a bit like trying to wrap your head around the subprime mortgage crisis: It may take more than a lifetime to fully grasp the concepts. In a nutshell, the blockchain is a distributed database—think a living, breathing spreadsheet operating in real-time—that audits itself every ten minutes and can’t be tampered with. An entire bitcoin network, for instance, relies on the blockchain as a shared public ledger. Every transaction of the cryptocurrency then is unalterably recorded.

As a result, people have started to look to blockchain technology for self-executing “smart” contracts and establishing a permanent and transparent provenance for digital art works. Blockchains, then, are the rough equivalent of notarizing every action.

That’s been of interest to Rhizome, a non-profit organization that works to archive important online art projects. Blockchain is the subject of a Rhizome-hosted panel happening on October 22; one of the panel participants is Kevin McCoy, the artist and founder of Monegraph, a recently-launched open source platform using the blockchain to help create licenses for the artistic or commercial use of an artist’s work.

Meanwhile, in Berlin, there’s the year-old ascribe, a blockchain start-up similarly giving creators the ability to sell their digital works with straight-forward licensing and transferring of ownership. They’ve already established partnerships with Berlin Art Prize in which they handle the submission forms and legal contracts with artists and Lumen Prize, an non-profit they will help launch the sale of digital editions with on a separate platform.

While in Berlin, we had the chance to speak with their creative team—including co-founders Trent and Masha McConaghy—to get a better sense as to what exactly ascribe offers to artists, and delve further into how it plans to specifically address the ongoing issues around the ownership, loaning and consigning of digital art.

Below is an abbreviated and condensed version of that conversation, which later continued via email.

“Tracking” Provenance

Rea McNamara: Despite the internet’s ability to proliferate content, a fundamental problem with digital art has been our inability to ensure creators are attributed and compensated for their work. ascribe is used to to create “time-stamping evidence” of these “ownership actions”, essentially establishing a transparent provenance recording the history of the title ownership. Why is this useful?

Masha McConaghy, Co-Founder: Selling [the title of a] digital work gets very difficult when you have 180 different countries who all have their copyright laws. [In every country, copyright duration lasts a different amount of time, and that affects artists’ image ownership rights.]

Masha McConaghy, Co-Founder: Selling [the title of a] digital work gets very difficult when you have 180 different countries who all have their copyright laws. [In every country, copyright duration lasts a different amount of time, and that affects artists’ image ownership rights.]

Before ascribe, you didn’t really have anything [that tracked the life of an art work]. Artists just send their files anywhere around the world, with no idea what rights they or the other person has.

We make the legal work very easy through ascribe. It’s an easy way to timestamp your copyright, and transfer your usage rights.

With ascribe, every action is contractual and relies on clear, concise contracts that are embedded in each transaction, and by default provide simple terms that transfer ownership or assign rights.

Jazmina Figueroa, Arts Coordinator: We provide proof of digital ownership through attribution and authentication. The work is timestamped on the blockchain. The work is authentic because the provenance is clear on the blockchain and always links back to the original creator. So there’s value for artists and collectors in that.

RM: That’s what strikes me as the most interesting thing that ascribe offers. You’re using blockchain to allow a digital artist to track provenance regarding their work.

MM: Blockchain builds transparency into digital provenance and that’s something future collectors will be looking for. When you go to any auction house, the provenance is crucial for validation and for ownership.

JF: For example, we’ve been talking to this artist in London named Ziggy Grudzinskas. He’s a painter who is represented by a commercial gallery in London, [and he’s] using ascribe to track the provenance of his physical paintings.

He was also concerned because photos of his work started appearing online.

RM: Right. This ties into concerns regarding social media, and the use of one’s work on those websites. What happens if your gallery’s strategy isn’t necessarily aligned with your own? That can be a concern.

JF: He’s been thinking about all these things. He’s made an Instagram and created hashtags so he could see where his work is on Instagram for himself, [since] he’s really concerned about where his work is, and what is happening to it.

RM: And your API has “analytics” tracking how their works are being used online without needing to be signed up for those sites.

JF: You want the publicity, you want people to talk about you, but you also want to have visibility into where your work ends up.

Paddy Johnson: What about if I take a screenshot of the work and upload it?

Trent McConaghey, Co-founder and CTO: It comes down to the difference between copy and title. Traditional approaches in digital try to enforce title—who owns what, or has licensed what—by trying to control copies, with ideas like self-destructing files, encryption, watermarks, and other DRM (digital rights management) techniques. But it doesn’t work, and won’t work, because it is fundamentally fighting the physics of bits. If I want a copy of an image, I can simply photograph it, and it will defeat any million-dollar DRM system in the world. This is the “analog hole” and it is why traditional DRM doesn’t work. All traditional DRM does is make files hard to use for people who are using it legitimately. Because of the physics of bits, people are going to have the copies all they want. But what they won’t have is [the] title, which gives them extra rights, such as right to re-sell, right to publicly display, and in general right to make money off the work. At ascribe, we don’t try to lock down copies; but we do lock down title, which is possible thanks to the combination of out-of-the-box licenses and blockchain.

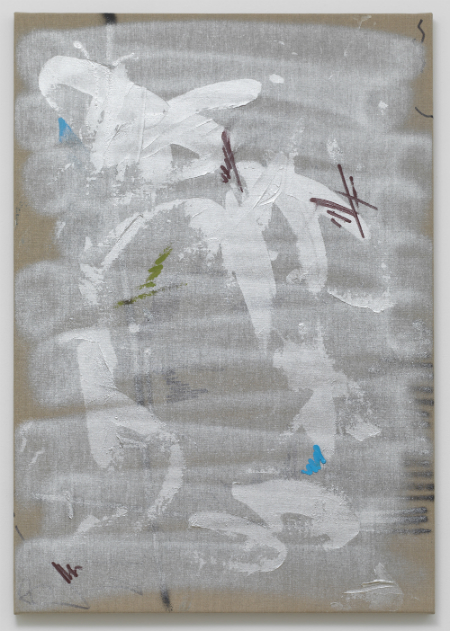

Jackson Hallberg’s “Green Leafage with Truck.” Thanks to ascribe, AFC now owns a limited digital edition of this work.

Blockchain and the Art Market

RM: In the 1990s, many artists found it an important political gesture for net.art to be free. Twenty years later, many of us have discovered we need to get paid. Have you met people who aren’t concerned with this?

RM: In the 1990s, many artists found it an important political gesture for net.art to be free. Twenty years later, many of us have discovered we need to get paid. Have you met people who aren’t concerned with this?

JF: We have spoken to a few artists who don’t care about ownership. But everyone cares about attribution, because that’s what opens up the opportunity for monetization, right?

Abigail Toll, Arts Administrator: I always think about Max Dovey in this scenario, because he’s an artist who deals with performance, and more ephemeral kinds of experiences. With his art, he doesn’t necessarily want to be represented by a gallery and is looking for alternative methods for generating revenue. He’s considering working with a producer to help build and create his brand, and shape him as an artist and then use that producer’s network to sort of get his work out there via social media platforms.

The ascribe Interface

Paddy Johnson: Rea and I signed up for ascribe accounts in order to accept the ownership rights of one of the artworks we’re featuring in this story, giving us the opportunity to play around with the ownership processing. We noticed the loan form have set time period fields, but the consignment form does not. Why is that?

Trent McConaghey: We did this to reflect the typical behavior in the art world that we’ve observed, including from Masha’s experience running a gallery and her colleagues. Loans are typically for museums with a specified start and end date. In our experience, consignment tends to be indefinite—we’ve seen artist-consigned work in sitting in the back rooms of galleries for more than a decade. We also reflect other practices from the art world in consignment: the consignee (gallery) can un-consign a work; and the consigner (artist) can request to un-consign a work but needs confirmation from the consignee (gallery).

PJ: The consignment has no fields for commission percentages or consignment splits. What is the rationale behind this decision? Is it just kept in the email-form record? (Normally insurance is a factor to consider too, but I assume there’s no reason to insure a digital work.)

TM: We focus on processing half of the value exchange, the ownership/licensing side. The other half—dealing with flow of money from collector to consignee and consigner—we leave to the system that they parties already use.

PJ: You also don’t charge upload fees. How does ascribe generate its revenue?

TM: ascribe generates its revenue from high-volume marketplaces, where we charge a small fee for each transaction. It’s important to us to keep the core webapp free, on behalf of creators who have traditionally got the short end of the stick. Some registries charge hundreds of dollars, which is just ridiculous. And, we can swallow it thanks to Moore’s Law—ever-shrinking transistors—which has made storage much cheaper than it used to be.

The Future

Rea McNamara: Where do you see ascribe going next?

Masha McConaghey: We are focused on digital art. Looking forward, we’re interested in 3D, photography and physical art.

[This is] a new and different way of collecting, and I think there will be new types of collectors emerging—we see it already.

RM: Who is this new collector?

Abigail Toll: It won’t be incredibly wealthy, established people anymore. it could be anyone who is interested.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }