Screen capture detail of Maria Jose Carlier Pimental’s interactive artwork at Sub Art Department

Online art exhibition The Wrong Biennale’s second iteration has been live for over a week now. But I’ve barely scratched the surface of its sprawling content. As one could gather from Paddy’s interview with founder David Quiles Guillo, this thing is massive. Artworks are spread across dozens of “pavilions”, each with its own curators and homepages. One such pavillion, Color Hybrids from curator Anthi Tzakou and Superscope requires the DIY virtual reality headset Google Cardboard to be fully experienced. Others depend on a dizzying array of hyperlinks, plugins, embedded content, and maddening navigation interfaces. Much like the internet itself, The Wrong is huge and unwieldy and generated by so many authors that it’s thematically and qualitatively inconsistent beyond recapitulation or even judgement, really.

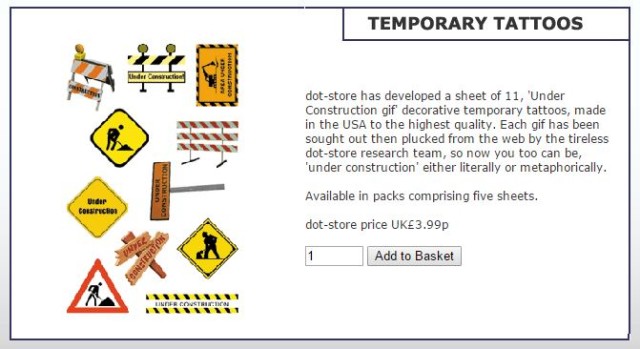

That being said, The Wrong’s greatest utility might be its capacity to lay bare all the strengths, challenges, and glorious failures of displaying and viewing digital art online. One of the best (and most frustrating) pavilions I’ve seen thus far comes from curators Cesar Escudero Andaluz and Mario Santamaría: Not Found, A Broken Net Art Exhibition. The page highlights the fragility of digital culture by assembling a collection of “dead” net artworks, mostly from the turn of the millennium, along with a description of each piece. Almost none of the hyperlinks still work, however artists Thomson & Craighead resurrected their 2002 piece “Dot-Store” with a new, functional URL. The page satirically recalls the dot-com-era’s optimistic commodification of the web, with “souvenirs” such as “under-construction” GIF temporary tattoos and tea towels printed with screen grabs of search engine results for existential questions. A tab labelled “fertilisers and pesticides” leads to the error message “These Weapons of Mass Destruction cannot be displayed” with other Bush administration/web ephemera puns in the “suggested actions” text.

A more contemporary (or perhaps timeless) embrace of web-site-specificity can be found in the pavillion Crystalized Skins, which offers free downloads of 3D models from 13 international video artists, that users can then remix. The curators were inspired by the 18th and 19th century practice of institutions collecting plaster casts of classical sculptures. These reproductions were intended for study and further replication through figure drawing or as models for paintings. In Crystalized Skins, the objects are similarly displayed out-of-context as sculptures that can be rotated and interacted with. Accompanying each object is an embedded Vimeo player with the video they were first created for. A few of the artists continue the classical allusion with works referencing archetypal figures from art history. Quayola’s “Captives” depicts a muscular statue trapped in/emerging from rock. The accompanying video is a triptych that gives the impression of rock being digitally squirted into a vitrine, alternately submerging and revealing the figure. Similarly, Geoffery Lillemon’s “Adam & Eve” exists as a deceptively elegant 3D sculpture when viewed as a stand-alone-object. When the source video is viewed, however, it’s revealed to be a surprisingly cartoonish animation of the iconic couple being doused in red viscous liquid. It’s evocative of the weird “sploshing” porn that occasionally makes its way from the more obscure corners of the internet to the meme circuit.

These exhibitions that couldn’t exist anywhere but the internet set a high standard that less interactive pavilions don’t always live up to. Nootropic Automat from curators Liaizon Wakest and Nıhıl Mınus, for example, is full of work that’s likeable enough but would probably be more engaging IRL than online (and will in fact open as a physical “embassy” exhibition in New Orleans January 9th). The title points to performance-enhancing psychopharmaceuticals, and appropriately the work here flirts between “mind-expanding” psychedelia and endurance work for one’s attention span. It’s heavy on abstract video pieces, which might be mesmerizing when installed in a gallery where they could become a conversation piece. As a succession of videos in a browser, though, they read like screensavers.

Other works are images intended to index online art periodicals, such as Xexoxial or Lin Tarczynski’s Geranium Lake Properties. It wasn’t until I right-clicked Tarczynski’s diagrammatic abstractions to view the JPEGs in a separate browser tab at a larger scale that I fully appreciated them. I couldn’t help but think how nice these would be as large prints rather than tiny thumbnails. Likewise, Tapecanvas’s experiments with analog video editing equipment seemed so self-reflexive to the medium of videotape and other obsolete, physical technology that viewing them as streaming content felt like a betrayal. Those tell-tale tracking lines from VHS players appear again in Karborn’s video work. Here, though, they’re less irksome because the piece reads as a compendium of everything that can go wrong with moving images across different media. Stills of geometric shapes seem to have been reproduced with grainy film, while artifacts from video tape as well as digital corruptions such as “datamoshing” transform human and animal faces from the realm of the familiar to terrifyingly alien masks.

It’s odd—after hours of viewing artwork online, still images can seem so anticlimactic. I found myself expecting them to provide some interactive component or hold a surprise beyond merely existing. Longer video work too seems to strain one’s attention span. The most engaging work in Nootropic Automat is probably a simple animated GIF from Teknari. It depicts a rectangular prism orbiting a log. I have no idea why this is such a satisfying image, but I could watch this loop forever. It’s one of the few pieces in the show that could only exist online despite having an old-school look that bucks the current aesthetic conventions of net art.

An animated GIF from Teknari in the pavilion Nootropic Automat

Pavilions in The Wrong are best when they embrace the internet’s weirdness, playfulness, and capacity for interactivity. Sub Art Department from curator Glenn Young is a great example. Here, viewers can manipulate a series of GIFs, text boxes, and images around an interface that looks like a postapocalyptic Wikipedia. Nearly every component is interactive, from Maria Jose Carlier Pimental’s pastel landscapes which can be re-arranged to pop-up chat boxes. Confusingly, some of the artist’s names hyperlink to individual pages, while others do not. The navigation is jerky and awkward and it’s hard to know who’s work is whose, but that’s part of the fun. I love this uncredited GIF of a plant wilting. It doesn’t loop, so it remains “dead” unless the page is reloaded.

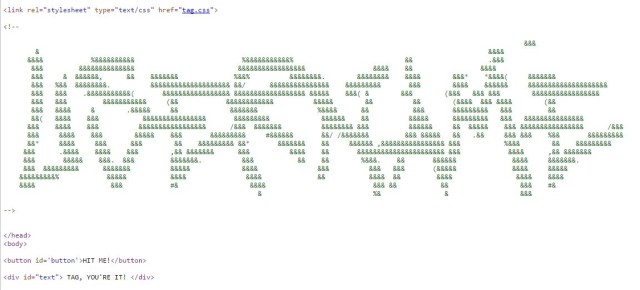

Similarly, the pavilion from Unnamed Group relishes in obscurity and frustration. The page will be updated by a different anonymous artist throughout the exhibition. When I visited yesterday, the page simply contained a button labelled “hit me!” that jumped randomly around the screen whenever a cursor came close to it. Wondering if there was actually more to the exhibition beyond the impossible link, I viewed the page’s source code, which just reveals the word “Username” as a series of graffiti tags in ASCII characters:

The whole Biennale is full of weird “Easter eggs” like that. All the awkward navigation, wonky layouts, and wildly inconsistent curation make the experience a bit like a scavenger hunt. That is to say, it can be frustrating but also fun if you aren’t looking for the work of one specific artist (tracking down individual works is daunting). So if you have a few hours to kill, let yourself get lost. Every once and awhile, you’ll stumble across something that’s really great.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }