Brian O’Doherty, ROPE DRAWING NO.19, REDUX, 1976/2016, rope, liquitex, nylon (all photos by author)

FORTY

MoMA PS1

22-25 Jackson Ave, Long Island City, NY

On view until August 28, 2016

Can alternative spaces and their anti-institutional goals ever be faithfully represented inside a museum? If MoMA PS1’s current exhibition FORTY is any indication, the answer is a definitive no.

What makes this realization even more awkward is that in this show, the alternative space and institution are one and the same. As its name suggests, FORTY honors the 40th anniversary of PS1 by looking back to its first exhibition Rooms. The show, like Rooms, is organized by Alanna Heiss who founded PS1 in 1976. The former alternative arts space was just one project launched under Heiss’ nonprofit Institute for Art and Urban Resources Inc.

FORTY revives Rooms’ art historical legacy through a selection of artists connected to the first days of PS1. Many of these artists even appeared in their inaugural show, which was heralded as a benchmark for post-minimalism and site-specific installation art. Eschewing ephemeral materials and archival photographs, the show mixes artwork from the 1970s with newly reconceived and recreated installations based on 1970s originals. These installations have been altered to respond to the new era and antiseptic aesthetic of MoMA PS1.

Despite this mélange of 1976 and 2016, the DIY attitude of Rooms and general alternative arts culture is lost. Instead, FORTY feels conservative and–ironically–institutional unlike its freewheeling and experimental past.

Take, for example, the entire second floor, which is so sparsely and reverentially hung, you’d think you were on a tour of a pristine white-walled commercial gallery. It doesn’t exactly scream 1970s counterculture. And it definitely doesn’t say anything about the old desolated and destroyed PS1 this show pays homage to. Lying dormant since its closure by the New York City Board of Education in 1963, PS1 in 1976 was covered in peeling paint, scraps of structural materials and leftover school supplies. With its messy loops of reproduced ephemeral materials, the museum’s concurrent Vito Acconci survey WHERE WE ARE NOW (WHO ARE WE ANYWAY?), 1976 more faithfully reflect the chaos and independent spirit of pre-MoMA PS1.

Keith Sonnier, Ba-O-Ba Fluorescent, 1970, foam rubber, ultra-violet neon light, masonite, fluorescent powder

Some of this institutional vibe undoubtedly comes from the later careers and art market desirability of many of the artists in FORTY. There are quite a number of big art world names in the show including Gordon Matta-Clark, Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, Daniel Buren and Keith Sonnier. Many became art market and museum darlings during and after the 1970s. Along with the glut of white walls, the space devoted to these major art sellers (unsurprisingly mostly white men) gives the show the feeling of an auction house showroom.

This curatorial style clashes with the bold experimentation that occurred in Rooms. In 1976, the general disrepair of PS1 gave the artists permission to thoroughly transform all of the building, filling the closets, classrooms, stairwells, boiler room, bathrooms and attic with art. The defunct building not only allowed artists to make additions to the space, but gave them license to further destroy it. “At least 50 of the 80 artists hacked, gouged, stripped, dug, poured and picked away at PS1’s rotting hulk–to their art’s content,” writes Nancy Foote in the October 1976 issue of Artforum.

Richard Nonas, Alligator (with side-men), 1976/2016, steel

What is missing from FORTY is a clear link between PS1 as a site for both creative and destructive possibility and today’s museum. Beyond basic wall labels, the only aspect conveying the history of PS1 was a selection of listening stations. Placed next to corresponding artworks, the audio consisted of interviews between Heiss and participating artists (The interviews and commentary are also available online).

While I rarely pay attention to audio guides, the artists’ conversations about the joys and challenges of creating inside a rundown school opened up some of the more impenetrable artworks. Brian O’Doherty’s colorful ROPE DRAWING NO. 19, REDUX, at first, seems like a snooze-worthy minimalistic installation with painted ropes tautly attached to the floor and ceiling. However, his audio description of the “liberation” he felt being able to “attack the wall, pull up what one wanted from the floor” in 1976 offered insight into his installation. Although site-specific spectacles such as O’Doherty’s might be common, Instagram-able sights nowadays, they represented a revolutionary reinvention of artistic opportunity in PS1’s foundational years.

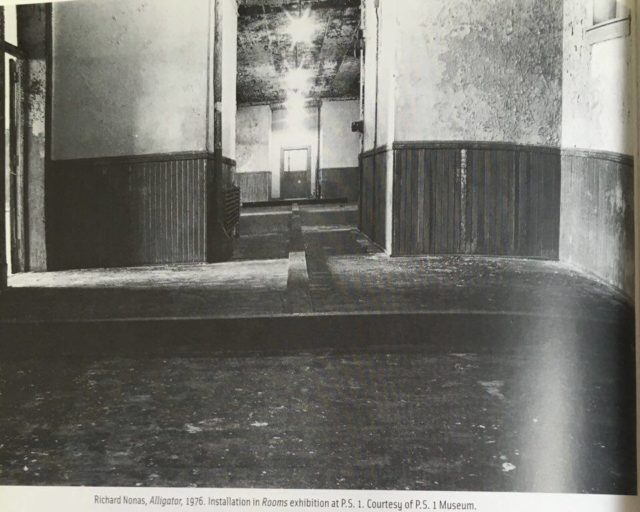

The archival image of Richard Nonas’ sculpture in Rooms from Alternative Art New York, 1965-1985

This remembrance of the liberation within Rooms is almost entirely absent visually. A selection of photographs or archival documentation from Rooms might have provided some much-needed context to FORTY. My own research proved as much. After viewing the exhibition, I returned home and looked up Rooms in the Julie Ault-edited publication Alternative Art New York, 1965-1985. The book–to my surprise–contains a handful of black-and-white photographs from PS1’s inaugural show including a snapshot of Richard Nonas’ Alligator (with side men).

Extending straight through multiple rooms, Nonas’ monumental steel sculpture seems to lie in the same location in Rooms and FORTY–a fact I didn’t realize until glancing at the photo. Alligator (with side men) in the photograph is surrounded by flakes of paint, dirty floors and chipping plaster. Rather than the cold, hypermasculine sculpture seen in FORTY, Alligator (with side men) exudes a haunting quality as it engages with the decrepit space. Nonas’ sculpture resembles an ancient ruin or an exposed part of the school’s foundation. It’s a mystery why none of this was laid out for viewers.

Colette/Laboratoire Lumiere, There’s a Mermaid in the Attic, 1976/2016, site-specific installation

To be fair, not all the works in FORTY are completely divorced from history. Take Colette/Laboratoire Lumiere’s There’s a Mermaid in the Attic, which successfully merges the past and the present of PS1, as well as the ephemeral and artistic. Appropriately installed in the attic, this seemingly illicit installation is made up of shiny fabrics, dresses on mannequins modeled after the artist, paintings and other detritus. It is thoroughly feminine and almost womb-like, thus confronting the hard-edged masculinity of the majority of the works in the exhibition.

Significantly, Colette uses her own archives to reveal her longstanding relationship with PS1 in There’s a Mermaid in the Attic. In a display case next to one of her immersive silk-draped interiors, the artist displays photographs of her similar attic-based contribution to Rooms and subsequent performances at PS1. These artfully arranged materials allow viewers to trace a lineage of her creative output from the 1970s to today.

There’s a Mermaid in the Attic felt fresh and more pertinent than its counterparts perhaps because of its ephemeral inclusions. While Colette’s installation aesthetically asserts female pride and power, its historical content also cements her place within the history of PS1 and the 1970s alternative art movement. Her deft mix of new art and archives suggests what FORTY could have been–a celebration of PS1’s humble radical roots and the continued relevancy of alternative spaces.

Comments on this entry are closed.