Installation view of ACT UP NY/Gran Fury, Let the Record Show…, 1987/re-created 2015, mixed media installation (all photos by author for Art F City)

Art AIDS America

Bronx Museum of the Arts

1040 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NY

On view until September 25, 2016

What is lost when HIV/AIDS becomes art history? A lot, as it seems.

As HIV/AIDS gets revisited by a slew of recent exhibitions, books and films, the real continued emotional impact of the disease is in danger of being replaced by a distant historical interest. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Bronx Museum’s current exhibition Art AIDS America.

The traveling exhibition, curated by the Tacoma Art Museum’s Rock Hushka and Jonathan David Katz, has been a public relations nightmare since its first installment. A decade in the making, the exhibition has endured criticism from both the left and the right.

In December, the Tacoma Action Collective staged a die-in protest last December at the museum in response to the exhibition’s jarring lack of black artists. Of 107 artists, only 4 identified as black. This provided a striking juxtaposition with the statistics from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which reveal the black community accounted for almost half of the new HIV diagnoses in 2014. After the protests, the curators agreed to retool their exhibition roster and public programming to reflect more diversity. At the Bronx Museum, this came in the form of adding six new works from the Museum’s collection, which is still a long way from giving proper representation.

This gap in representation can be attributed to the curators’ over reliance on the art historical canon–a canon largely made up of white cisgender male artists. In a cringe-worthy interview published in conjunction with the protests, Hushka was pressed by two artist/activists, Christopher Jordan and Charhys Bailey, on the curatorial decisions that led to the underrepresentation of black artists. Hushka admitted that they “were looking for artists who’ve had a pretty robust museum exposure, versus looking for artists that…[trails off] We wanted more of the artists who were already known.”

Maybe Hushka and Katz felt they couldn’t convince museums to mount an exhibition about HIV/AIDS that wasn’t canon-focused. Originally, the exhibition was billed at the Tacoma Art Museum as the “first comprehensive overview” of the impact of HIV/AIDS on American Art. Now at the Bronx, the curators’ have revised their statements, removing the claim that it’s comprehensive. Instead, it’s the “first exhibition to examine the deep and ongoing influence of the AIDS crisis on American art and culture,” which also isn’t true. Since the beginning of the crisis in the 1980s, there have been exhibitions exploring the effects of AIDS on American art and culture–they just weren’t as large in scale or as obsessed with the canon.

Keith Haring, Altar Piece, 1990 (cast 1996), bronze with white gold-leaf patina

Which brings us to the Bronx. The curators’ dependence on the art historical canon is seen almost immediately. Inside the entrance of the main galleries stands Keith Haring’s shiny silver triptych Altar Piece, which was his final work. While a stunning funerary monument, Haring’s status as an art historical superstar reflects much of the show’s population.

There aren’t too many surprises with museum-friendly artists such as David Wojnarowicz, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Frank Moore, Paul Thek, Robert Mapplethorpe and Martin Wong represented. The exhibition feels as if you’re flipping through an art history textbook. It’s also just as cold and impersonal. It should, instead, fill viewers with grief, sadness, rage and other complicated emotions.

Even with ACT UP and Gran Fury’s illuminated sign declaring “Silence = Death” looming overhead, the show seems–ironically–silent. Some of this silence is literal. There are select few videos in the exhibition, rendering the white-walled galleries a hushed tomb. This silence is especially deafening in contrast to the noise and passionate screams of activists who fought–and continue to fight–AIDS. Many of whom died of complications from AIDS.

On one hand, it is difficult to criticize Art AIDS America. It isn’t easy curating an exhibition about HIV/AIDS. With the impact of the virus still ongoing and many living with HIV/AIDS, there is no clearcut and safe historical distance. Curators also have to grapple with difficult issues–sex, homophobia, drugs, illness, death, disease and activism. These are often not in the wheelhouse of many major museums.

Perhaps because of this, HIV/AIDS has been historically underrepresented in art institutions. While that is changing in recent years, the curators have been honest but unspecific about the challenges they faced trying to find museums willing to put on a show about AIDS. The exhibition represents a step in the right direction for AIDS visibility. And yet, I hoped for more.

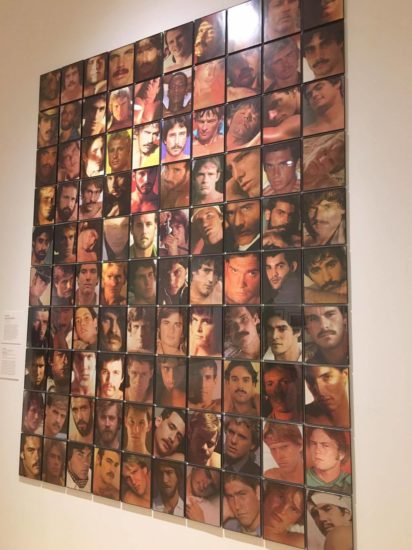

Pacifico Silano, Pages of a “Blueboy Magazine,” 2012, 100 pigment prints

Art AIDS America, to be fair, does do a better job than many other museum exhibitions that reference AIDS. This is achieved through the many intergenerational links forged through the exhibition. By refreshingly positioning younger artists like Pacifico Silano or Kia Labeija alongside canonized artists, the exhibition importantly disproves the harmful assumption that the HIV/AIDS crisis ended in 1995 with the appearance of the AIDS cocktail. Unfortunately, this inclusion of today’s artists working with AIDS activism is all too rare.

The problems with the show prove just how essential curating can be, particularly for an exhibition dealing with such an emotionally fraught topic. The work on display is not just art or even, activism. Instead, it represents people’s lives and, sometimes, deaths. The work contains the memories of loved ones who passed or the artist’s own illnesses, which makes the sloppy curation almost unforgivable.

The wall labels present perhaps one of the biggest missteps of the exhibition. With numerous factual errors and weak generalizations about the HIV/AIDS pandemic, the labels are distracting and, in some cases, hilarious. Walking through the exhibition, I found myself laughing at the labels. Laughter probably shouldn’t be my response to a show on HIV/AIDS.

Take, for example, the label for Jimmy DeSana’s photograph Stool, which depicts three nude male bodies circling a drain. The text highlights a quote from DeSana describing the alienation of gay artists from the mainstream art world. His important statement is overpowered by its attribution, “As DeSana said in 1999,” which would have been 9 years after his death from complications from AIDS. While seemingly minute–and hopefully, by now, edited by the museum, Jimmy DeSana’s resurrection does a disservice to his legacy.

Brett Reichman, And the Spell Was Broken Somewhere Over the Rainbow, 1992, oil on canvas

Another label for Brett Reichman’s rainbow and clock-filled And the Spell Was Broken Somewhere Over the Rainbow shows the generalizations perpetuated through the show. The text describes the height of San Francisco gay culture that was shattered by the AIDS epidemic. The label reads, “As AIDS ravaged San Francisco and a generation of gay men suffered while lesbians cared for them as they died, the mythical qualities of the city seemed to dissolve slightly.” Who was this army of lesbian caretakers? It is true that many lesbians–and others–stepped in as de facto caretakers for individuals were alienated from unaccepting families. However, they weren’t all dying gay men and caretaking lesbians. The AIDS pandemic also did more than “dissolve slightly” the halcyon daydream of 1970s San Francisco.

The labels, however, are not the only issues with the show. Rather than seek out black artists in the New York area that make work about HIV/AIDS (off the top of my head: Frederick Weston, Mark Bradford, Jack Waters…), the curators drew from the Bronx Museum’s permanent collection.

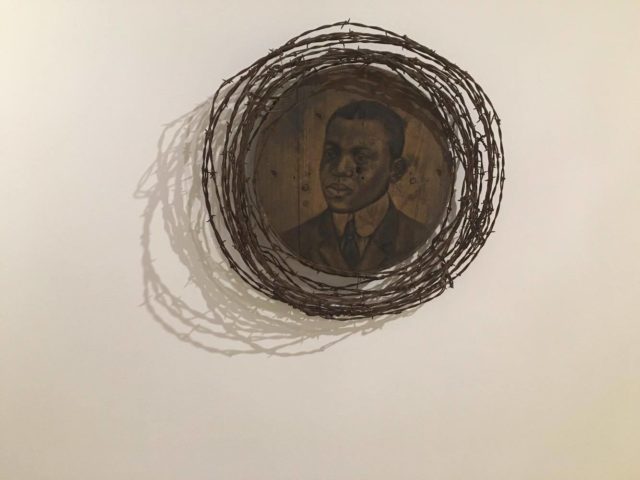

This meant, in some cases, the work did not seem to engage with HIV/AIDS at all. Artist Whitfield Lovell’s portrait Wreath is a prime example of this curatorial stretch. Lovell’s circular Wreath depicts a faded charcoal portrait of a young black man that resembles a vintage photograph. The wooden piece is wrapped with barbed wire, reminiscent of a crown of thorns. To me, Wreath addresses the continued violence against young black men and its connection to the history of subjugation and slavery. Sure, HIV/AIDS can be understood as a part of this narrative, but that is a leap.

Whitfield Lovell, Wreath, 2000, charcoal, wood and barbed wire

So why include Wreath if it seemingly doesn’t have anything to do with HIV/AIDS? The wall label explains the piece as “Although Wreath was not created during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis [Note: it is dated 2000], the work nonetheless strikes a melancholy, even macabre tone, evoking the confinement and oppression suffered by those afflicted with the virus.” If evoking confinement and oppression is enough to be a part of the exhibition, then couldn’t technically any artwork about civil rights fit as well? Why this one? I suspect it may have to do with the ease of having the work already in the museum’s collection.

Given the period between the December protests in Tacoma and the Bronx Museum’s opening in mid-July (never mind the decade of preparation), the curators certainly had enough time to find artists of color who do clearly explore HIV/AIDS in their work. Whether intentional or not, the exhibition’s messy curation seems to declare that viewers should just be happy with the mention of AIDS. That we, as viewers, should ignore its obvious faults and exclusions since it is a museum show focused entirely on HIV/AIDS.

Well, AIDS is not enough. A show about HIV/AIDS in American art deserves to be well-curated. It needs to be intersectional and diverse. It needs to reflect both the strength and voices of activists and the quiet mourning of the bereaved. Instead, Art AIDS America feels nothing but institutional.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }