Aneta Grzeszykowska: NO/BODY

September 7 – October 16, 2016 | 11R | 195 Chrystie Street, NY NY 10002

September 7 – October 16, 2016 | Lyles & King | 106 Forsyth Street, NY NY 10002

Installation shot from 11R. Aneta Grzeszykowska, “Skin Head #1,” recycled leather, 2016; “Selfie #15,” and “Selfie #10,” both pigment ink on cotton, 2015.

What’s on view: A solo show spanning two galleries. In 11R: several photographs of female body parts carefully sculpted from pig skin: a mask being painted with needles in its cheek, a hand missing fingers, a breast. Two black leather masks, one with cat ears. Three films in a darkened room featuring naked choreographed performers.

In Lyles & King: More videos and photographs, this time of the artist’s body painted in various colorways. In the center of the gallery, twin sculptures of a female body in white and black leather, respectively, recline on the floor.

“Selfie #6,” 2014. At 11R.

Paddy: There’s an idea in art that because it’s supposed to be timeless it should be immune to trends. In reality we all know that’s not true and this smart show by Grzeszkowska is a good example of that. If this exhibition took place even five years ago, I could imagine myself being dismissive of its goth flavor. Two female busts adorned with black leather masks on pedestals sit in the middle of the room, one with cat ears, and one of the more visually striking photographs documents a voodoo doll with lips being painted red. Not too long ago, I might have connected these qualities with a kind of shock art you’d normally see in galleries catering to art tourists.

The flavors of it as we see here, though, don’t spark that kind of reaction from me. Grzeszkowska draws from a sci-fi goth aesthetic sensibility that makes suffering and terror appear sexy and attractive. That quality alone imbues the show with a sense of unease and even dread.

Michael: Ha! I love all things goth, and in some ways this show hit a lot of the right notes. Watching the video pieces, especially, I was reminded of the Brothers Quay and their over-the-top macabre sensibilities.

Excerpt from “Headache,” digital video, runtime 11:37, 2008.

Michael: But Grzeszykowska’s work also exists in this hyper-specific pocket of horror/fascination with the incomplete/severed body. I thought of Jala Wahid’s recent image essay about the mutable body in Sci-Fi, art, and personal histories—the horror of clones or the strangeness of cyborgs or the state of being a refugee where one is hyper-aware of one’s own body. Actually, I just noticed that both Wahid’s essay and Grzeszykowska’s exhibition text cite Polish sculptor (and holocaust survivor) Alina Szapocznikow’s work as an influence.

I have to say, I was a little disappointed when we arrived at 11R because I was really hoping these creepy body parts would be physical sculptures rather than prints (and I think we both had some concerns over presentation). But after visiting the other half of the show (which is really a totally separate body of work) at Lyles and King, I think the artist’s interests may lie in manipulation of images and negation of “portraiture” moreso than prosthesis or implied violence. As in, a photograph of an individual becomes its own sort of terrifying clone—where the subject gives up a degree of agency or control over how they are edited/re-contextualized/replicated.

Paddy: Meaning, the photograph is a clone of the body and in the digital world, you have no control over how it’s edited and interpreted?

Michael: Right! It seems like there’s a lot of discussion lately about how one’s image lives on as a second-self that we lose authorship of after it’s produced—whether it’s one’s face on Instagram or disembodied dick pic or breasts, fingerprints, biometrics, etc…

“Selfie #4,” pigment ink on cotton, 2014.

Paddy: I agree with your thesis and will add that the work titles at 11R-most of which are Selfie #1,Selfie 2 etc-support that idea. Many of the images look as if they are documentation of the making of a clone. For example, a sculpted breast detached from any body is held out, as if it is being submitted for evaluation, a hand holds a detached thumb as though it has just come out of a shop. You’d think that creating a dummy for manipulation might be a way for the artist to assume some control over her image, but the voodoo mask suggests that she’ll feel every cut and collage.

The most disturbing image wasn’t the lifelike voodoo mask, but the woman’s hand with two and a half blackened prosthetic fingers laid out and a child’s hand manipulating the still life. The idea that all of this could be a vision of our children seems terrifying.

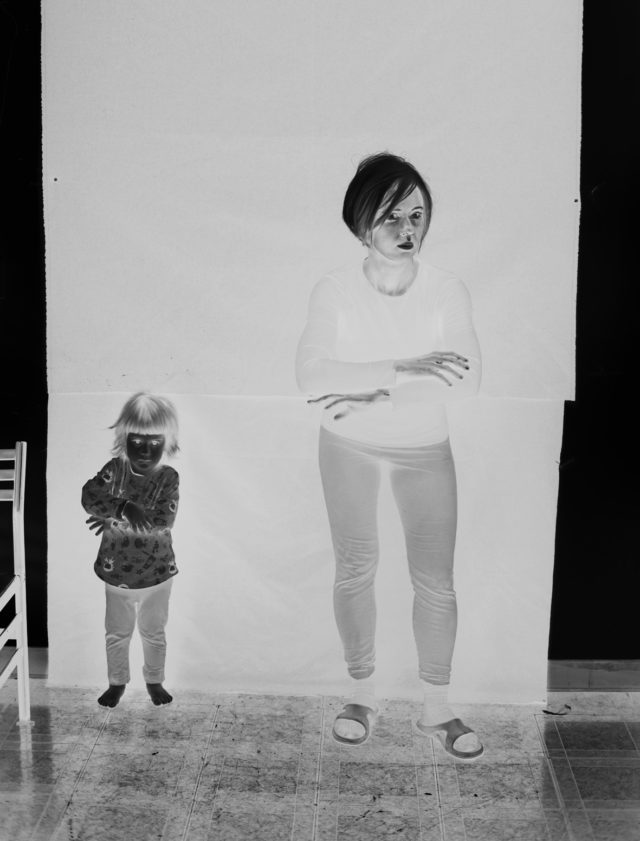

Excerpts from “Negative Process,” digital video, runtime 6:13, 2014. At Lyles & King

Michael: The first piece one sees walking into Lyles & King is an enormous video projection of the artist (who is caucasian) painting herself jet black. As an American viewer, particularly in light of unfortunately-recent, surprisingly-ongoing discourse about blackface, my knee-jerk reaction was “WHAT THE FUCK IS SHE THINKING?” It then becomes apparent that this is an ontological exercise related to photography: Grzeszkowska contours, drag queen/Kardashian-style, with white paint as her shadow, creating a negative image of herself that reads as “correct” when photographed in inverted contexts, including her un-painted, caucasian family. The end result is a series of black-and-white surreal images wherein Grzeszkowska reads as a nude from a painting standing in alien environments, “other” from the negative-image people around her.

“Negative Book #25,” pigment ink on cotton paper, 2012/2013.

Honestly, I don’t find this offensive and I think it’s the type of thing that—yes—is defendable and makes sense. I see a lot of toying with cliché and “special effects” tropes in Grzeszkowska’s work. But really, why wouldn’t someone in 2016 just do this in color? Especially in the context of work that’s about “otherness” or the body made grotesque, painting yourself black just opens a can of worms that we shouldn’t have to devote this much time to scooping back up, just so it can be knocked over again and again. Are black and white photography and cinema really the most relevant points of reference in discussions of portraiture? When compared to ubiquitous color selfies or even oil painting, I think not. I’m not saying I personally find this series problematic, but I know that no one would find this problematic if she’d just painted herself in purples and blues (the actual negative image of flesh) and produced the series in color.

Paddy: Maybe it was too hard to get the effects needed in purples and blues? I could see a botched version of color photographs being more offensive than just opting for the black and white version.

Michael: Ha! I’m sure that’s true. I think we live in an era where the risk of offence probably outweighs rewards for risk-taking.

Speaking of color, one of my favorite pieces in the Lyle & King space was one of the few in color, “Negative Make Up” In the image on the left, Grzeszykowska wears foundation and lipstick in their prescribed zones. On the right, she’s covered her lips with foundation and the rest of her face in lipstick. It’s so good:

“Negative Makeup,” archival print on cotton paper, 2016.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }