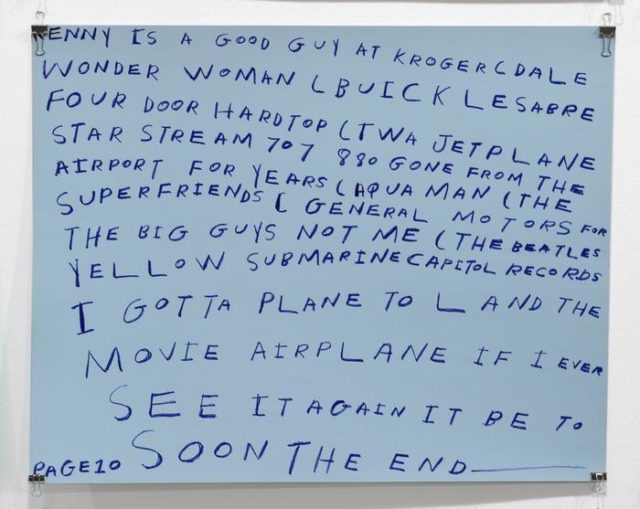

Detail of Dale Jackson’s Untitled, ink on posterboard work at White Columns (Courtesy the artist and White Columns)

Continuing my exploration of the West Village galleries’ September shows, I ventured above Houston Street to Maccarone and White Columns:

Coming To Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-Plicit Art By Women

Installation view of Carolee Schneemann and Marilyn Minter at Coming To Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-Plicit Art By Women at Maccarone, 2016 (Courtesy of Maccarone)

Maccarone

630 Greenwich Street and 98 Morton Street

New York, NY

On view until October 16

Now here’s an exhibition remarkable for loudly asserting its importance and then failing to live up to its own hype.

Maccarone’s Coming To Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-plicit Art By Women restages artist and curator Ellen Cantor’s 1993 group exhibition at David Zwirner (Artsy has a history of the show’s curation). The recent iteration is organized by Pati Hertling and artist/Clit Club founder Julie Tolentino as a part of a multi-gallery revival of Cantor’s work this fall.

There’s no question that the original show continues to be a significant feat in the representation of sexuality and gender in art up to the 1990s. Just a quick glance around the black-walled gallery reveals works by key feminist greats like Carolee Schneemann, Marilyn Minter, Louise Bourgeois, Lynda Benglis, Joan Semmel and Hannah Wilke. The presence of these iconic contemporary artists likely accounts for the jaw-dropping popularity of the show, which was slammed with people when I visited.

However, what was radical in 1993 is a college art history course in 2016. Many art viewers will be familiar with several key pieces in the show like Nan Goldin’s photographs from Ballad of Sexual Dependency or Schneemann’s Interior Scroll. While other exhibitions have successfully revived the strengths of these works–often by giving them a new contemporary context, hanging them one right after the other was like flipping through required reading in a feminist art class. If you emphasize the importance of these works over and over again, the art start to lose its revolutionary edge. Even a naked Lynda Benglis holding a dildo gets old.

Ellen Cantor, Mad Honey (top section), 1990-91, carved wood and oil paint (photo by author)

Certain works do feel fresh like Nicole Eisenman’s hilariously and violently sexual notebooks, G.B. Jones’ dyke pin-ups drawings and Cantor’s own orgiastic totem paintings. And the show also includes a performance programming series, focusing on younger, often queer artists.

Ultimately, though, the show looks more like a time capsule than an ongoing conversation about issues of representation that still continue to plague the art world. That would be fine, were it not for the last decade of rethinking gender and sexuality. The show could have benefitted from a visual dialogue with current sexually explicit art by women, including trans and gender non-conforming artists. As it stands now, the restaging just doesn’t seem like enough to revive the innovative nature of Cantor’s original vision.

Dale Jackson, Tony Just, Ben Morea and Danny Thach

Installation view of Dale Jackson at White Columns, 2016 (Courtesy of White Columns)

White Columns

320 West 13th Street

New York, NY

On view until October 22, 2016

There’s a limit to how many shows can successfully exist in one gallery, and White Columns definitely exceeds that number with four individual solo shows. Not only does this decision force you to juggle four checklists and press releases, it also unwittingly puts artists in competition for the viewer’s attention.

In this case, the two outsider artists came out on top. Danny Thach’s obsessive Keith Haring appropriations and Dale Jackson’s bold textual drawings far outshine the stiff and studied abstract work by Tony Just and Ben Morea. In particular, Dale Jackson and Tony Just’s textual works provide a stark juxtaposition that may not have been noticeable if these exhibitions weren’t together.

With a staggering amount of neon-colored sheets of paper tacked onto the walls, Jackson’s art, at first, looks like minimalist studies of the color, form and utilitarian simplicity of art store paper. On closer inspection, each paper is covered in a fury of writing.

Affiliated with Visionaries + Voices in Cincinnati, an organization that works with artists living and working with developmental disabilities, Jackson narrates his life through these drawings–his work at Kroger, his Beatles obsession and fascination with cars. His commentary ranges from movie criticism (“the movie Airplane if I ever see it again be too soon”) to the day-to-day (“Must be a party going on next door”). Taken as a whole, Jackson’s work is a moving physical embodiment of the internal monologue that we all have.

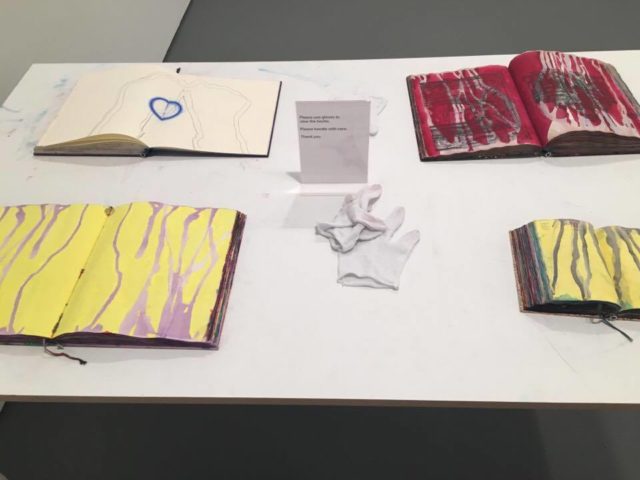

Installation view of Tony Just at White Columns (photo by author)

Nearby, Tony Just’s exhibition pales in comparison to the universal relatability of Jackson’s work. Take, for example, Just’s vintage book artworks, which are covered in a combination of watercolor, gouache, wine and grape juice. While the use of grape juice and wine certainly references religious ritual, this same rigid devotion extends to the viewing experience. Viewers are required to put on crisp, white archival gloves to precariously page through his paint-splattered copy of Albrecht Dürer’s Complete Woodcut Prints. It feels sterile.

This would not be notable otherwise, but it comes as a glaring contrast to Jackson’s exhibition, which also features a table of his large poster-sized works for viewers to handle. with his drawings, you can use your bare hands. While this is likely due to their chosen materials, the difference in Just’s formality and Jackson’s ability to connect with the viewer–even on a physical level–is unmistakable.

Comments on this entry are closed.