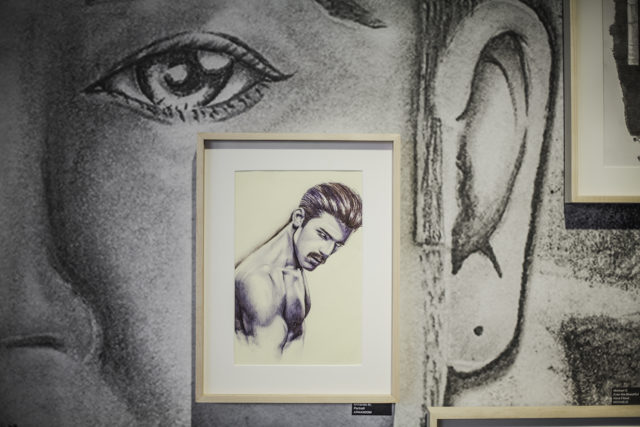

Installation view of On The Inside including “Portrait” by Armando M. (Photo by Christopher Watkins)

On The Inside

Abrons Arts Center

466 Grand Street

New York, NY

On view until December 18, 2016

After Donald Trump’s election, private prison stocks soared. While this small but ominous tidbit might be overshadowed by the glut of other horrifying news pouring in since Tuesday, it makes On The Inside, a group show of incarcerated LGBTQ artists at Abrons Arts Center, that much more crucial.

Curated by Tatiana von Fürstenberg (yes, the daughter of designer Diane von Fürstenberg), the exhibition is an essential reminder that art can be harnessed for activism. Many shows claim to make the invisible visible, but rarely does the work come from the silenced populations themselves. Von Fürstenberg organized the show in collaboration with LGBTQ prisoner grassroots organization Black and Pink. They placed an open call for art in their monthly newsletter, which reaches 10,000 prisoners. The response was overwhelming, receiving around 4000 submissions from prisons in all fifty states.

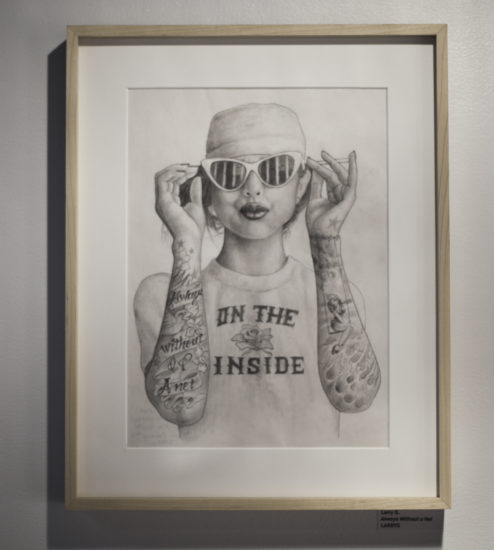

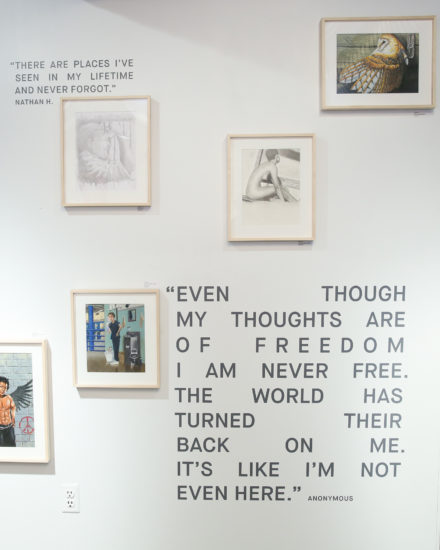

The exhibition itself is overwhelming, covering almost every blank wall in the arts center. Even the windows have decals on them listing all the artists involved in the project. Numerous pencil and pen drawings on notebook paper (the materials most prisoners have access to) are hung from floor to ceiling on walls covered in quotes from the prisoner’s letters describing their experiences. The art ranges from empowering self-portraits that explore trans, gender fluid and two spirit identities to an entire wall of interpretations of Rihanna. Overall, portraiture reins supreme and powerfully reveals the universal drive to self-represent in the face of their invisibility.

I spoke with Tatiana von Fürstenberg about the organization of the show, the difficulty she had placing a social justice-focused exhibition in New York’s art institutions and how she thinks art can encourage political change.

I’m glad we ended up talking on Thursday after the election because On The Inside seems to be even more necessary in this context.

None of the people behind bars–those are three million votes that we don’t have. When you come to the show and see the talent, the brilliance, the poetry and the strong points of views that these artists have, you realize these are three million very important votes. One of my goals with the show is that people come and realize that we can’t afford to lose these people. We’ve heard the same old voices–the voices of the people who have made it–over and over again. The voices we need to be listening to are the ones we don’t ever get the chance to hear.

Larry S., Always Without A Net (Photo by Christopher Watkins)

That’s a great segway into the show. The organization was a multi-year collaboration between you and Black and Pink. How did that collaborative relationship start?

I made a pledge to do an act of love every day for thirty days between Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday and Valentine’s Day. Because of my own mobility issues, I thought that being a pen pal was something that I could actually do for thirty days. I found Black and Pink, which probably has the best pen pal matching facilitation service out there. I found them on the internet and started reading the back issues of their newsletter. These issues were filled with letters and some art. One of the letters that first struck me was from this 21-year old guy who wasn’t out to his family yet. He was in a car with someone and the car turned out to be stolen. He got arrested and had to come out to his family. And they never spoke to him again–just a letter saying, “You must be mistaken. My son is dead.” That really struck me.

So many people who get incarcerated are already marginalized before going to prison because of their sexuality or gender expression. They’ve been rejected by their own family of origin or employers. I never actually got a pen pal though–something bigger happened. I got the idea for art almost immediately after meeting with them.

The show is arranged around certain overarching themes, which corresponds to both the art and the quotes on the walls. How did you approach the show’s curation?

I feel like I imposed very little on the show. The art categories found themselves. All the love related ones are very tender and close. All the different ways of expressing gender polarity. And the quotes are a really big part of the show too. They are taken from the letters that accompanied the art. Some of the quotes are by artists who are not actually in the show. In some cases, people expressed themselves better in a more poetic way. The art and quotes work in tandem.

I didn’t want to be dogmatic about the way I showed the work. Yes, there is a clear order, but it was my way of moving through the show in a cohesive way.

Installation view of On The Inside (Photo by Angela Pham / BFA)

One of the most noticeable aspects of the show is the preponderance of self-portraits. What did you make of the frequency of self-presentation?

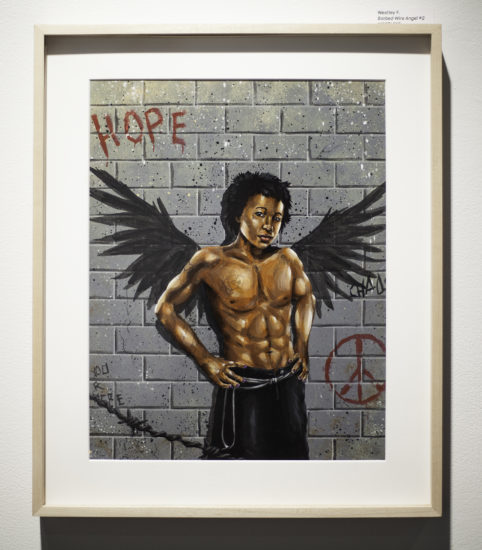

What really struck me was that very few of the self-portraits are within the context of prison. Almost none are wearing their uniforms. They’re very clearly saying, “Forget about that. This is who I actually am. See me and hear me for who I am. I’m an artist and I’m a queer person. I’m talented and resilient. And miraculously, I don’t feel defeated even though life has been really unfair to me.” Prison guards are assaulting these people in criminal ways that are much greater than any crime they’ve committed. And to not break, still be able to create beauty and participate in this call to action is huge.

Almost all of the art in the show is figurative portraiture. Did this surprise you?

I didn’t know what to expect, but I didn’t expect portraiture. It thought, “Oh my god, everyone wants to be seen.” They want eye contact. It’s very man-to-man, woman-to-woman and eye-to-eye. They’re saying, “I’m a human being–a hot human being, a powerful human being or a human being that still has faith.”

I had a really hard time finding a place to do the show. I went to many, many conventional art institutions that had very little interest in the show. I had studio visits with people from art institutions and it was immediately off-putting and condescending. Someone said, “Oh, we expected the art to be more outsider art.” What does that even mean? The fact that you made that assumption makes it even more critical to do the show. You think art only belongs to successful people? You think talent only belongs to people on a pedestal? That’s not true. I’m thrilled that it’s at Abrons since it’s connected to the Henry Street Settlement, which is founded on inclusion. It worked out perfectly.

Just the term “outsider art” is incredibly problematic, especially in this case.

It’s a really ugly label and I tried to be careful how to frame the show. I wanted to give LGBTQ artists who happen to be currently incarcerated an exhibition in New York City. It feels good that I was able to do that–it’s a rare opportunity. We hear the same 100 or 1000 voices of successful artists over and over again. It’s time we started listening to the voices we don’t get to hear. That’s why I wanted to offer an immediate way to give back with the texting response.

Westley F., Barbed Wire Angel #2 (Photo by Christopher Watkins)

I’m glad you brought that up. You set up a text messaging system in which viewers can text a number with the artist’s code on the labels. The message will then be transcribed and sent to the artist. Why was this important for you to provide a way for viewers to communicate with these incarcerated artists?

Many people behind bars get no outside letters. They feel totally forgotten and worthless. I also wanted to make it so you can’t just enjoy this art on your nice Sunday after brunch and before your nap. I wanted to make it really easy to give back and to make it more equalizing. You can make a real connection. Now that you’ve seen the art and learned that even though we’re taught to believe that people behind bars are dangerous to society, it’s not true. You see all this complexity of humanity, emotion and depth. Now, it’s time to connect. It’s the right thing to do.

On the Inside speaks to the intersection of activism and art. Do you think art is able to enact political change? How?

Yes I do. I think the directness of the art in the show is a revelation. My goal is to cultivate a culture of compassion. I want to connect people and cultivate compassion and empathy. Connecting humanity is ultimately a political goal. It’s the same as how parenting or education can be political. You’re utilizing your energy or voice to cultivate the culture you want to live in.

Creativity is a valuable resource. And it’s ok to make direct and earnest art. I’m not sure people know that. When I was faced with art institutions that turned the show away, I was almost led to believe that it wasn’t enough. Social justice wasn’t enough to be in the art world. I don’t get it. Well, then what is art supposed to be? We’ve been taught it’s not supposed to be decorative. Then, what is it? These are incredibly refined, powerful portraits that are being used to escape, express or communicate.

Comments on this entry are closed.