Installation view of Sinister Feminism at A.I.R. Gallery (Courtesy the artists and A.I.R. Gallery)

Sinister Feminism

A.I.R. Gallery

155 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY

On view until February 5, 2017

One of the few positive side effects of Trump’s chaotic pussy-grabbing rise to power is the revitalization of feminism as an active political tool. Between the Women’s March and women-driven exhibitions like Nasty Women, women are now at the forefront of the resistance to Trump’s dangerous administration. The strength of this feminist revival explains why the failure of A.I.R. Gallery’s 12th biennial exhibition Sinister Feminism is such a disappointment.

Rather than a strong rebuke of a misogynist administration, Sinister Feminism, curated by Piper Marshall with Lola Kramer, shows a stubborn refusal to scrap wonky aesthetic concerns in a time of political emergency. Not only is the exhibition’s attempt to rethink feminist art’s essentialism hackneyed, it also felt disassociated from reality.

Sinister Feminism begins with a jolt. A sculpture, 8am Woman on the Subway, by Chelsea Rae Klein sits slumped in a corner right inside the entrance like a mannequin in a haunted house. Made of newsprint-stuffed nylon tights with long, black hair hanging off its ass, it appears as if viewers mistakenly stumbled into a crime scene. This uncanny shock is only compounded by B. Quinn’s two giant slabs of butter hanging nearby like a wall of gelatinous human fat.

Installation view of Sinister Feminism at A.I.R. Gallery (Courtesy the artists and A.I.R. Gallery)

From here, the show continues into the next two rooms of the Dumbo art space, expanding on Klein and Quinn’s disgusting representations of the body. An acrylic painting by Caitlin Keogh depicts a headless torso covered in tassels in a pattern that wouldn’t look out of place on a designer scarf. On another wall, Lizzy Marshall’s Mother’s Tongue presents a disembodied tongue with black and grey lines slashed through the picture plane. And on a pedestal, Dolores Furtado’s Sacrum is a mound of purplish resin that resembles an anatomical model of an unidentifiable body part.

With a glut of depictions of fractured and ambiguous bodies scattered around the gallery, it’s clear Marshall, with Kramer, intended to launch a reconsideration of the body in feminist art. Marshall’s curatorial statement discusses these works in terms of “transition,” a more fluid, inclusive form of feminism that stands apart from the strictly gendered body. But, not only is this attempt to transcend the physical body in feminist art nothing new (Louise Bourgeois and Kiki Smith distorted the female body long before the artists in Sinister Feminism), none of these included works were particularly successful at it. The pieces felt safe and kind of boring, not to mention irrelevant in our fraught political times.

Some of the ceramics club (cc)’s Untitled (Hillary’s) (photo by author)

This isn’t to say all the included works forgo politics. However, faulty curatorial choices distracted from their efficacy. Take, for example, ceramics club (cc)’s Untitled (Hillary’s), a collection of small ceramic Hillary Clintons awkwardly positioned on a high shelf that wraps around two walls. These representations of Hillary Clinton vary widely. In one sculpture, she flies through the air like a feminist superhero, while in another, she snuggles up to President Obama. Unsurprisingly, the entire shelf features a colorful array of pantsuits.

I appreciated the installation’s exploration of Clinton through kitsch, but with the sculptures sitting so close to the ceiling, I had to resort to staring at the works through the camera function on my phone. And even then, I couldn’t discern the detail of the material or process. I only came away with a vague recognition of their subject. Perhaps unfairly, it left the installation looking like a display of tchotchkes in a suburban home.

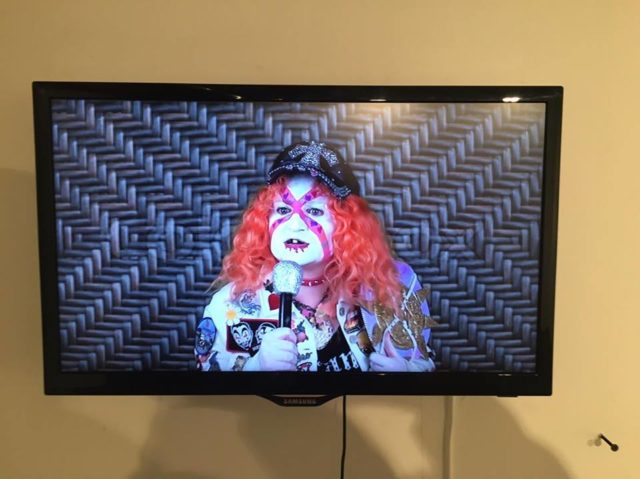

Installation view of Bailey Scieszka’s Wicker Cage Promo (I-III) (photo by author)

The only work that resonated with our insane contemporary political state was Bailey Scieszka’s collection of videos Wicker Cage Promo (I-III). Scieszka appears in the video with orange hair, a bedazzled baseball cap, a jacket covered in Insane Clown Posse patches and a terrifying face full of pancake makeup. She looks like a combination of a Juggalo, Tim Curry’s evil clown in It and Hulk Hogan. It’s actually scary.

With a wrestling belt slung over her shoulder, the artist lip-synchs a trash-talking rant by a man. While not obviously related to politics, Scieszka’s overblown bluster and rambling insults mimic President Trump’s seemingly endless supply of hot air. By exaggerating hyper-masculine speech, Scieszka equates this egomania to clownishness, pointing out its sheer ridiculousness. And it could not feel more timely. “Clowns come into your life and test you,” she blurts. They sure do.

Scieszka’s Wicker Cage Promo (I-III) presented a bright spot in a dim show, but I still left the exhibition feeling disheartened. I hoped a feminist art space like A.I.R. could, at least, match the relevancy and importance of feminism in our national politics. Instead, Sinister Feminism felt like an attempt to avoid socio-political engagement by fixating on well-trod aesthetic territory. And in such a nightmarish time for women nationally, we can’t afford to look backward.

Comments on this entry are closed.